After an abrupt reversal 20 years ago, some prisons and colleges try to maintain college education for prisoners.

September 8, 2016

To get to the 99A college prep English class at California's San Quentin State Prison, you pass through two security checks, two gates and a very thick, very old metal door that looks medieval. You walk into a courtyard surrounded by guard towers. Inmates in pale blue scrubs with the word "PRISONER" printed on the back in bright yellow are hanging around, playing baseball and chatting.

Across the yard sits a cluster of portable trailers. These are the education buildings, and they're where the Prison University Project holds its classes.

One evening early this year about a dozen men sat at tables in one of the trailers, notebooks and pencils spread before them beneath the fluorescent lights. A guard supervised from a corner of the windowless room.

Once this was a not uncommon sight in an American prison, inmates doing hard time but working on a college degree that might help them get a job or otherwise adjust on the outside.

Every year 700,000 inmates leave prison, and there is ample evidence that those who have a college degree are less likely to come back. But, as the nation prepares an increase in the number of released prisoners, as reforms to sentencing guidelines for some drug offenses kick in, programs like San Quentin's have become a rarity.

Entering and leaving the prison system

The Obama administration recently launched a pilot project to expand higher education among some inmates, but for now prisoners at San Quentin seem destined to remain among the few who have access to a college degree behind bars.

On that spring night, a volunteer teacher named Lisa Kelly, a graduate student from University of California, Berkeley, led the class. The discussion focused on essays by Malcolm X, Helen Keller and the jailhouse poet Jimmy Baca.

At one table, Sydney Johnson and James Wortham sat together, older men with greying facial hair. They spoke slowly as they talked about the themes they've identified in the readings: perseverance, the power of language to change a life. Wortham has been in the California prison system for more than 30 years, convicted of second-degree murder at 19. He heard about the Prison Education Project while at a different prison and requested a transfer to San Quentin to attend. He hadn't heard of Helen Keller or Jimmy Baca. "It blew me away," he said.

"Helen Keller really didn't have to suffer that much," Johnson countered. He's 50, incarcerated since 1998, and if he graduates from the program, he'll be the first person in his family to receive a college degree. Johnson was mostly impressed that Helen Keller had a private tutor who visited her at home and taught her one on one. He'd never heard of such a thing, and to him, it represented the height of privilege. "Even though she had her little disability, it didn't mean she grew up hungry," he said.

Malcolm X's essay resonated more with Johnson, particularly the part of his story where he came to prison with an 8th grade education and taught himself by reading the dictionary.

"I like how he took his frustrations and used it as a motivating piece, he was driven to learn to speak better," Johnson said. "And that resonated with myself because I feel I don't speak articulate enough. That's another reason why I want to go to college. So I can learn to better speak."

Some of the men enrolled have life sentences and may never get out of prison. But Wortham will be up for parole soon.

"I have a lot of people counting on me and I want to do the right thing and not let them down," he said. The city he came from and wants to return to, Richmond, Cailfornia, is plagued by violence, and Wortham felt partly responsible; he said he could see the aftershocks of the murder he committed at age 19 still radiating through his community. "I'm educating myself because I don't want to go out there [as] I came in. I don't want to be the same way, because I would behave the same way."

Cost-benefit of prison programs

Fighting recidivism

More than two million people are in prison or jail in the United States. Almost every one of them will come out. So when prison populations boom, as they did in the 1990s, so do the eventual populations of former prisoners.

"We have that naive perception, OK, we solved this crime, we caught this guy, we sent him to prison, we can forget it," said John Linton, the former director of correctional education programs at the federal department of education. "But those individuals do come back into our community. It's a question of what kind of condition do they come back in?" It's also a question of whether they are able to stay out of prison. Education, it seems, is one of the best and most cost-effective means of achieving that goal.

The recidivism rate — the rate at which people return to prison after they're released — is hard to calculate, and estimates range widely. But it's generally accepted that almost half of people who leave prison will be back behind bars within three years.

A 2013 report from the Rand Corporation found that when inmates received any kind of educational classes while they were in prison, their recidivism rate dropped by at least 13 percentage points. When they took higher education classes — college programs — their recidivism rate dropped by 16 percentage points.

In other words, if you take 100 inmates who don't get education in prison, about 43 will be back within three years of their release. If you take the same 100 inmates and give them a college education while they're incarcerated, three years later only 27 will be back.

At almost $32,000 to incarcerate a person for a year, "that's a very large reduction," the lead author of the Rand study, Lois Davis, said. "When you look at the range of rehabilitation programs and how cost effective they are, and their effect on reducing recidivism, it tends to be fairly modest. But what we were able to show for educational programs, is that they're highly cost effective." For every dollar spent on an education program, Rand found that roughly five dollars were saved on reincarceration costs.

Pell fight

At one time, thousands of prison inmates were attending college. About 350 college degree programs operated in prisons.

A big factor was the federal money aimed at helping low-income students pay for college, a program started in the 1970s and known as Pell grants, named for its sponsor, Sen. Claiborne Pell, D-R.I. When the program began, prison inmates were eligible for Pell funds. "Education is our primary hope for rehabilitating prisoners," Pell said. "Diplomas are crime stoppers."

But in the 1960s, crime rates started to rise. By the 1980s and 1990s, a sense was developing that what the nation needed to do was put more people in prison and make prisons worse places to be.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle lined up to denounce what they called a new wave of soulless criminals. Newt Gingrich spoke of a "drug addicted underclass with no sense of humanity, no sense of civilization and no sense of the rules of life in which human beings respect each other." Then-First lady Hillary Clinton described so-called "superpredators" with "no conscience, no empathy".

"What happened is the issue about free college got swept up into 'Let's get tough on crime, let's do more severe sentencing, let's eliminate parole, let's have three strikes you're out,'" Linton said. "It was a general 'Let's not be nice to prisoners anymore' movement. And Pell grants was one easy target for that."

"We started to hear that folks were not happy with the fact that we were getting a free education," said Sean Pica, who in 1994 was incarcerated in New York for murder and was taking classes through a local college. "There were people in the system that were very optimistic, saying, they would never take away college. Why would they possibly take that away? It's the only thing that gives us a chance of staying out."

But in 1994, Congress stripped Pell grant eligibility from prisoners.

Colleges and universities pulled out of prisons after that. By 2005, just 12 college programs, in 12 prisons, remained.

"Literally one day, the college programs, they came and packed up the crates with books, unplugged the computers and walked out of the prison," Pica said. "And it was gone."

Programs today: Sparse and varied

Prison inmates are perhaps the most observed group of people in the country. They are counted multiple times a day; they are watched over by guards and monitored on security cameras.

But we don't know how many of them are taking college classes. One estimate puts enrollment rates at 3 to 6 percent of inmates, in college and vocational classes combined. Exact comparisons are hard to make, but participation in degree-granting college programs is down considerably since the 1980s and 1990s.

And the landscape of education programs in prisons is volatile, reflecting the instability in funding for prison education.

After Pell grants disappeared, the funding sources for prisoners seeking an education came and went. For a few years starting in 2002 a pot of federal dollars called Incarcerated Youthful Offender Grants paid for some education programs for people under 25 and within five years of release. That money was cut in 2011.

States have occasionally paid for college in prison for a few years, and programs would thrive for a year or two and then disappear, when legislators changed their priorities and cut off funding. Some prison education programs are set up as non-profits, funded by donations and run by volunteers. Some inmates take correspondence courses by mail.

One result of this varied source of funding is a wide range in offerings. Some prisoners in Florida are studying hydroponics and beekeeping, for example. South Carolina teaches cattle breeding and milk processing, and in New York State, some prisoners are studying braille transcription. In New Hampshire, where only 15 prisoners are enrolled in higher education programs, many are taking correspondence courses to be pastors and paralegals. And Georgia has just opened its prisons to a state-based degree-granting institution for the first time since Pell grants went away in 1994. Officials decided to contract with a school called Life University, the largest chiropractic college in the world, known for its rugby team and its adherence to a philosophy called "vitalism." The 15 prisoners and 15 correctional officers in its program will earn Associates degrees in something called Positive Human Development and Social Change.

Officials in other states had no idea how many inmates were taking classes or what they were studying. Often, even the administrations in charge of prisons don't know the number of inmates in their prisons who are enrolled in post-secondary education.

The Obama administration signaled at least some change recently when it announced a three-year pilot program called Second Chance Pell. Starting with the 2016-17 school year, it is granting Pell money to about 12,000 inmates in 67 programs at prisons across the country at an estimated cost of $30 million per year.

Critics say the program is a misuse of executive power. But a U.S. Department of Education spokesman said, "America is a nation of second chances. And the evidence is clear that providing opportunities for education, treatment, and training for everyone - including individuals who have made mistakes and are in prison - is one of the most important things we can do to help people get their lives back on track and become contributing members of society."

The government is encouraging prisons to focus their programs on inmates within five years of release.

'My education is for me'

But preparing for life on the outside isn't the only value for some.

San Quentin's Prison University Project was founded in partnership with Patten University, a California college, in 1996, in the wake of the 1994 bill that barred prisoners from Pell grant funds. PUP is set up as a non-profit, funded by individual and foundation donations; classes are taught by volunteer faculty. Students pay nothing.

About 350 students enroll in classes each semester with the program, studying humanities, social sciences, math, and science, and eventually earning Associates of Arts degrees.

Most students start in PUP's college preparatory classes in math and English.

As a group, prison inmates have, on average, dramatically lower levels of academic attainment than the general population. Thirty-seven percent of people in state prisons didn't finish high school, compared with 19 percent of the general population. More than half of the general population has at least some postsecondary education; only 14 percent of state prison inmates do.

Education attainment

"Most of our students on average dropped out of high school between 9th and 11th grade and then completed a GED in prison," Jody Lewen, head of the Prison University Project, said. "A lot of students come in not knowing exactly what a paragraph is, or how to write a grammatically correct sentence, or what it is to write an outline or a thesis statement."

The Prison University Project has set an ambitious goal for itself: to take men who may have never graduated high school, who haven't had any formal education for decades, and step by step, turn them into students who can succeed in a college classroom. In 99A, that means writing a lot of essays.

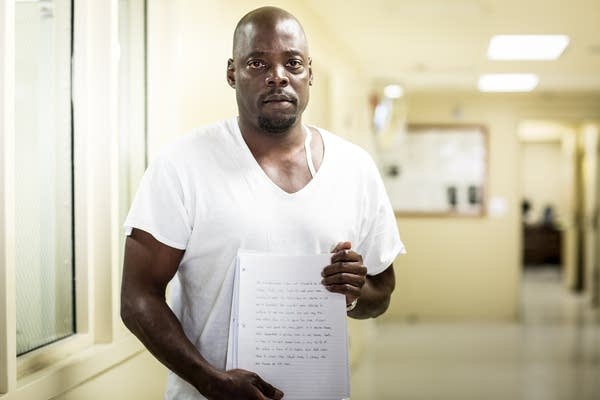

Clarence Long was one of those students last spring. He said he hated school growing up; teachers ignored him or punished him, but he said they never really taught him. "I went all the way to 11th grade, I just never learned how to read while I was in school," he said. "They just passed me on."

Long dropped out in 11th grade, started dealing drugs, and in 1985, was convicted of strangling an ex-girlfriend who had threatened to tell police he was selling cocaine. At 27, sitting in a prison cell and wondering what to do with the rest of his life, Clarence decided to teach himself to read. It took him 19 years. Then he enrolled in a GED program. "When I graduated from getting my GED they said, we're going to sign you up for college," he said. "I was like, really? I thought I was done with school! Now I'm going to college?"

Long said class had been challenging. "It's the first time I ever had to do a lot of homework," he said. "I'd never formed an essay before." Long knows he may never be released from prison, meaning all the studying and homework will have done little in terms of preparing for a life on the outside.

But he said that for him, that wasn't necessarily the point. "My education is for me," he said. "If I don't never get out, I'm still going to get my education."

Correspondent/Producer: Samara Freemark

Editor: Catherine Winter

Web Editor: Dave Peters

Web Producer: Andy Kruse

Associate Producers: Ryan Katz, Suzanne Pekow

Technical Director: Craig Thorson

Research and Production Fellows: Lila Cherneff, Alex Baumhardt

Additional Reporting: Briana Breen

Project Manager: Ellen Guettler

Senior Producer, Education Projects: Emily Hanford

Executive Editor and Host: Stephen Smith

Managing Director and Editor in Chief: Chris Worthington

Special Thanks: Liz Lyon, Dylan Peers McCoy

Support for this program comes from Lumina Foundation and the Spencer Foundation.

Feedback

We're interested in hearing what impact APM Reports programs have on you. Has one of our documentaries or podcasts changed how you think about an issue? Has it led you to do something, like start a conversation or try to do something new in your community? Share your impact story.