Learning to love tests

If there's consensus on anything in education, it's this: Tests are awful. But maybe we've been thinking about tests all wrong. Research shows that tests can actually be powerful tools for learning -- but only if teachers use them right.

If there’s consensus on anything in education, it’s this: Tests are awful. At best, they’re a necessary evil, something that teachers, parents and students all hate, but that we tolerate in the interest of assessing how well our students are learning.

But maybe we’ve been thinking about tests all wrong. Research shows that tests can actually be powerful tools for learning, but only if teachers use them right.

The medical student

I met up with Michael Young on the campus of Georgia Regents University’s medical school in Augusta, Georgia, where he’s a student. Young has neatly combed hair, a quiet voice, and an intensely earnest manner. Every time I saw him over the course of two days, he was wearing a clean, pressed, white lab coat.

Young is in his third year now, but he had a rocky start to medical school. He nearly flunked out, and he says that was because he was studying wrong. In fact, most of us study wrong. Researchers say we could learn more, learn it faster, and remember it better if we didn’t make the kinds of mistakes Young was making.

Young decided he wanted to be a doctor while working as a counselor at a drug abuse clinic. He was impressed with how much more the doctors were able to do to help the patients who came in to the facility. So he approached the nearest university, Columbus State, to ask about premed programs.

“They kind of laughed at me,” he says. “They said, ‘Well, we don’t really have a premed program and besides, people from Columbus State don’t go to medical school.”

Young persisted and finally convinced the school to put together a modified premed program for him. It was a bit haphazard, he says now.

“Since they didn’t have a Bio 2 class, I ended up taking fishing to meet that requirement,” he remembers. “So we went out to the river and waded around, and we actually dissected a fish one time. So that’s something.”

Young got through it and managed a decent score on the medical school entrance exams. He was thrilled when he received an acceptance letter from Georgia Regents. But when he got there, he found he was not prepared for med school.

Young’s first medical school class was biochemistry. From the first day, he felt like he was drowning. He didn’t understand any of the notations, the formulas, even the vocabulary the professor used.

Halfway into the semester, the class took its first test.

“I studied from the time I woke up in the morning until the time I went to bed, 16 hours a day,” Young says. “I took my notes, read them. When I finished, read them again. When I finished, read them again. And I said, ‘Okay, I’ve got this. I memorized it in the book. I know this. I’m just going to do great.'”

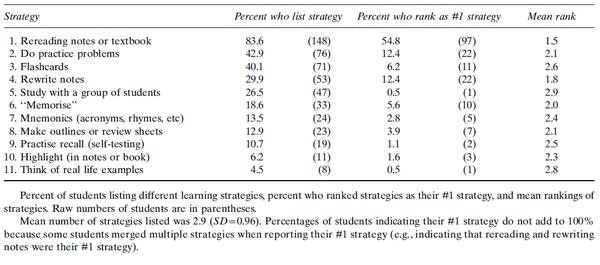

This is actually exactly how most students study. Rereading is by far the most common study strategy for students in higher education. A recent survey of university students found that 83.6 percent of students choose rereading as a study strategy. That’s probably because rereading feels good. Once you’ve reread a chapter a couple of times, you really feel like you’ve got it, and in the short term, you do. Research shows that people can remember stuff they just read really well.

But it turns out that rereading is almost totally ineffective for long-term remembering, even remembering that has to happen just a day later. Which Young found out on that first biochem test.

“I get to the test, and I just have no idea,” he says.

Everything that Young had been so sure was lodged in his head just vaporized. It was as if he hadn’t studied at all. He ended up getting a 65, a failing grade.

The same thing happened on his next couple of tests, in all of his classes. Young’s first semester grades were terrible.

But instead of giving up or dropping out, Young decided to approach his problem scientifically.

“I asked myself the question: am I doing everything right?” he says. “I knew that the answer wasn’t studying more, because I knew there was no way to study more than what I did. And I thought, ‘Well, maybe I’m just not studying the right way.'”

So Young went to his computer and started searching for answers. He started by typing ‘How to improve memory’ into his browser window. Predictably, this turned up a bunch of junk, and so he started poking around in the academic research. And that’s how he came across Henry Roediger.

The testing enthusiast

Roediger — who goes by Roddy Roediger — is a psychology professor at Washington University in St. Louis, the head of the school’s Memory Lab, and a memory obsessive who’s been studying how and why people remember things for four decades.

About 20 years ago, Roediger was running an experiment on how images help people remember. He separated his subjects into three groups and asked each group to try to memorize 60 pictures. The first group just studied the pictures for 20 minutes. The second studied them for most of that time, but was asked to recall the pictures once during the session. But Roediger tested the third group on the pictures three times over the 20 minutes.

“Seven minutes, they recalled what they could, little break, seven more minutes, take their sheet away, do it again,” he says. “Another seven minutes, [they were] bored out of their minds. They thought, ‘This is awful.'”

But when Roediger tested the three groups on the pictures a week later, there were huge differences in how much they each remembered. The first group, which had just studied the whole time, remembered 16 of the 60 pictures. The second group did a little better. But the third group, the ones he had driven crazy by testing them over and over, did great. They remembered 32 pictures — twice as many as the first group.

This phenomenon — testing yourself on an idea or concept to help you remember it — is called the “testing effect” or “retrieval practice.” People have known about the idea for centuries. Sir Francis Bacon mentioned it, as did the psychologist William James. In 350 BCE, Aristotle wrote that “exercise in repeatedly recalling a thing strengthens the memory.”

But the testing effect had been mostly overlooked in recent years.

“What psychologists interested in learning and memory have always emphasized is the acquisition part. The taking [information] in and getting it into memory,” Roediger says.

Laypeople — and even experts — tend to think of human memory as a box to be packed with information.

“What people neglected and didn’t think about was the getting it out part,” Roediger says. “We don’t get information into memory just to have it sit there. We get it in to be able to use it later. … And the actual act of retrieving the information over and over, that’s what makes it retrievable when you need it.”

Why does retrieval, or quizzing, slow forgetting and help us remember?

“It’s a good question, and we don’t know the answer to it,” says Roediger’s colleague Mark McDaniel.

One theory is that the act of retrieving information from the vastness of our memory systems poses a challenge to the brain, and retrieval practices that act: in effect, greasing the wheels of memory.

Another theory is that information goes into our brains attached to context. The texture of the book page that we flip as we read; the hum of the air conditioner in the background; the taste of the chips we’re snacking on as we study: these all become part of a stored memory.

“Memory is dynamic, and it keeps changing,” says McDaniel. “And retrieval helps it change.”

Every time a memory is retrieved, it becomes connected to new sensations and contexts.

“The more things you have it connected to, the easier it is to pull it out, because you have lots of different ideas that can lead you to that particular material,” McDaniel says. “And the things you retrieve get more accessible later on, and the things you don’t retrieve get pushed into the background and become harder to retrieve next time.”

Coming across the research from Roediger’s lab completely changed how Georgia medical student Michael Young thought about studying.

Roediger and Young struck up a correspondence. They exchanged lengthy messages.

“I’m sure I bugged him so much,” Young says. “I was emailing him constantly.”

The first thing Roediger told Michael: Stop rereading. Instead, start testing yourself. Read a chapter, look up from your book, try to recall what information you just took in. Make up little quizzes for yourself.

That kind of studying was harder for Young. He says it felt uncomfortable, inefficient. It made his head hurt.

“This is a difficult way to study,” admits Mark McDaniel. “I think most people want learning to be easy and effortless. They want a magic bullet for it. And learning is not easy and effortless. It takes work, and it takes effort and time and dedication.”

But the more Young studied using retrieval, the more things came together for him. His grades improved. Soon, he was making A’s. And he’s become something of a legendary tutor around Georgia Regents, spreading the gospel of study skills and the testing effect.

Sydney Baranovitz came to Young for tutoring after failing her first neuroanatomy test, and she credits him with saving her medical career. “I didn’t know how to study,” she says. “I had the ability; I just didn’t know what to focus on. The issue with learning is, no one ever sits down and teaches you [how to study].”

Mark McDaniel agrees. “One of the gaps or problems in the educational system is that no one ever helps a student figure out how to learn, and yet that’s the primary challenge a student is faced with. You’ve got to assist them with how to do that. And that’s where I think we’re failing somewhat.”

More tests, not fewer

It’s not just that many students are never taught how to study. It’s also that many classes, especially in higher education, are set up to encourage bad study habits.

I met Andrew Sobel in his office on the campus of Washington University in St. Louis. Sobel is a professor of international studies, and he used to teach a freshman introduction to political science class. He structured it in the traditional way, with daily lectures, a midterm exam and a final.

Then he heard Roddy Roediger give a presentation on the testing effect, and Sobel realized that his students were studying in exactly the wrong way, by rereading their notes the night before his two exams.

A vastly better model, Sobel thought, would be one where he essentially forced his students to retrieve knowledge over and over again throughout the course.

So, every semester, instead of two exams, he started giving his students nine quizzes. All these little tests would count for a grade, but they would also, Sobel hoped, be a tool for learning.

At first, Sobel says, his students hated the quizzes. But he was shocked when he realized that by the end of the semester, his students were writing answers to his questions that were comparable to those of his upper division students.

“That had never happened before,” Sobel says. “And so the only thing that can explain that, the only thing that varied in there was the testing structure.”

Sobel has tried to talk to his colleagues about the results he was seeing with quizzing, but he says most of them aren’t interested in switching from a few exams to multiple quizzes.

“University faculty are considered very smart, but are also very conservative,” he says. “We don’t like to change our ways.”

“I’ve always said there was kind of a conspiracy between students and faculty,” says Roddy Roediger. “Faculty hate making up and grading tests. Students hate taking them. So we pretend they’re not very important, and we don’t give them. … [Our lab] is arguing for more testing, not less — not standardized tests, but tests that help kids learn.”