A teacher loses faith in the Common Core

New York teacher Kevin Glynn was once a big fan of the Common Core, but he says the standardized testing that's come along with it is reducing students to test scores and narrowing what gets taught in schools.

Kevin Glynn used to be a hedge fund trader. But seven years ago he ditched Wall Street, moved to Long Island, and become a third grade teacher. He didn’t need much convincing when it came to the Common Core. “My kids in the classroom, they needed this,” he says. “It was a jump, we were going to strive for something more.”

He felt like he knew the kinds of skills and knowledge that were required in the real world, and he didn’t think American kids were being challenged enough in school. He liked what he saw when he read the Common Core State Standards – the focus on critical thinking, on communication skills, on a deeper understanding of math.

He became a passionate advocate for the Common Core. “I put my heart and soul on it,” he says. “I spoke on behalf of it. I was convinced that this was it.”

But Glynn has changed his mind.

“Common Core has been a disaster in New York,” he says. “It’s turning kids into test scores.”

Taking action

Glynn co-founded a group called Lace to the Top. The name is a play on Race to the Top, a federal grant program that encouraged states to adopt the Common Core State Standards. It also required states to put new systems in place that use student scores on Common Core tests to evaluate teachers and principals. That means how students do on Common Core tests can ultimately affect how much teachers and principals are paid; it can even get them fired. In other words, the new Common Core tests are high-stakes – too high-stakes, says Glynn.

He founded Lace to the Top as a protest against what he calls the “negative effects of high-stakes testing.” Lace to the Top supporters are encouraged to wear bright green shoelaces to show solidarity with the cause. If you visit schools on Long Island, you’ll find teachers – and students and parents too – wearing these bright green laces.

The problem with high-stakes testing, Glynn says, is that teachers wind up spending a lot of time drilling kids on how to pass the tests, rather than actually teaching. And subjects that aren’t on the tests – like art and music – get short shrift.

In the past, the negative effects of testing were most evident in schools where a lot of the students were low-income and struggled to pass state tests. But at higher-income schools, where kids tended to do better on those tests, there wasn’t as much focus on test prep.

Now though, with the new, more challenging Common Core tests, even teachers at higher-income schools are worried about whether their students will pass. (To read more about the Common Core tests and how they are different from previous state tests, click here.)

For example at Kevin Glynn’s school, Brookhaven Elementary School in Brookhaven, New York, most kids were proficient on the old state tests. But on New York’s new Common Core tests, first given in 2013, only 29 percent of students at Brookhaven scored proficient in math. Thirty-six percent were proficient in English Language Arts. Schools across the state saw similar test score drops.

The Wall Street Kevin Glynn might have seen those test scores as proof of what’s wrong with American schools. But the Kevin Glynn who’s been teaching third grade for seven years sees things differently.

A test worth teaching to?

Before he was a teacher, Kevin Glynn looked at test scores the way he looked at numbers on a balance sheet; test scores told you how kids were doing, the way a balance sheet could tell you how much money you had.

But what Glynn has realized is that tests are much more powerful than that. They don’t just measure learning; they have a huge affect on what gets taught. And when schools like his are suddenly told that two-thirds of their students aren’t up to par – and that teachers might eventually lose their jobs because of it – things change quickly. What gets taught is what gets tested, he says. And when he looks at New York’s Common Core test, he doesn’t see a test worth teaching to.

As evidence, Glynn refers to a document from the New York State Education Department that shows only about 15 percent of the Common Core standards were tested on the state’s 2013 third grade English Language Arts test. Almost every question tested one of the Common Core reading standards. There were no questions that tested the writing standards or the speaking and listening standards.

“I’m just baffled that anyone finds value in this,” he says, pointing to the third grade test. (The New York State Education Department refused to go on the record to answer questions about the test, and there has been no independent analysis of how well New York’s tests are measuring the Common Core.)

Glynn’s concern about New York’s test is that teachers will react by focusing more on reading, and less on writing, speaking and listening, all skills that he thinks are critical. He liked the Common Core standards when he first read them because they emphasized writing and speaking and listening. (You can read the standards here.)

“But in a high-stakes system, teachers teach to the tests, not the standards,” he says.

Glynn is not the only one complaining about the New York tests and the impact they’re having on what’s being taught in school. According to interviews with more than a dozen teachers and school administrators in five different districts, students in New York are taking more practice tests, and they’re spending more time on math and reading – and less on other subjects – since Common Core was put into place.

The need for tests

Supporters of standardized testing say tests are necessary. Without them, there’d be no way to be sure kids are learning, or to identify schools or teachers that are failing to provide students with a good education. John King, education commissioner for the state of New York, said in a 2014 speech that tests are necessary to hold educators accountable to parents and taxpayers.

“Parents trust us with their children,” said King. “And the people of the state trust us with billions and billions of their tax dollars. And what they ask in return is that we deliver results, and prove it.”

But Kevin Glynn is concerned about the impact that high-stakes testing is having on students, particularly young students like the third graders he teaches.

“They are told, at the tender age of eight, ‘there’s a giant test coming up and you must perform well on it,'” says Glynn. “And these kids take it, and then they get rubber-stamped at the end of the test, ‘you are a failure.’

“If you tell a child they’re a failure, they’ll meet your expectations every time,” says Glynn. “Tell them they’re more than a score, and you’ve got something.”

Enough is enough

Kevin Glynn’s school district, South Country Central in Patchogue, N.Y, was set to start six weeks of Common Core test prep in the Spring of 2014. But at a meeting in late February, the district announced that test prep was cancelled. Test-prep was getting in the way of good learning, officials said.

“My school district decided to take its six weeks of test prep and remove it,” says Glynn. Suddenly, teachers had six weeks of lesson material to come up with, and Glynn says they loved it.

“It was refreshing, and you saw teachers excited,” he says.

The third grade teachers at Brookhaven took their six weeks and created a blog project and a biography project.

For the blog project, students read about topics in the news – including Amazon’s proposed drone-delivery system and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s efforts to extend Internet access in the developing world. Students formulated their own opinions about these topics, then wrote op-ed pieces with supporting facts and evidence. They published their pieces online.

Glynn says the assignment fulfilled several of the Common Core 3rd grade English Language Arts standards, including “referring explicitly to text as the basis for answers” and learning to “distinguish their own point of view from that of the author of a text.”

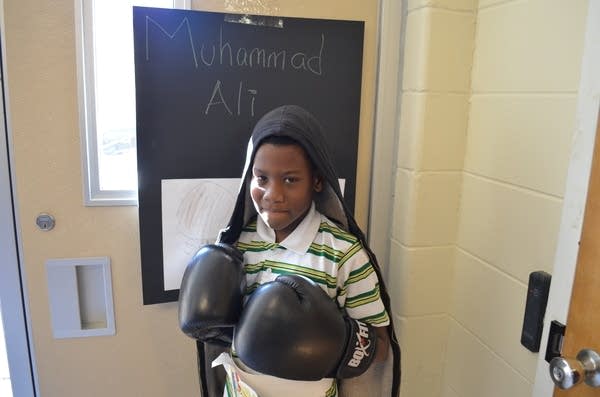

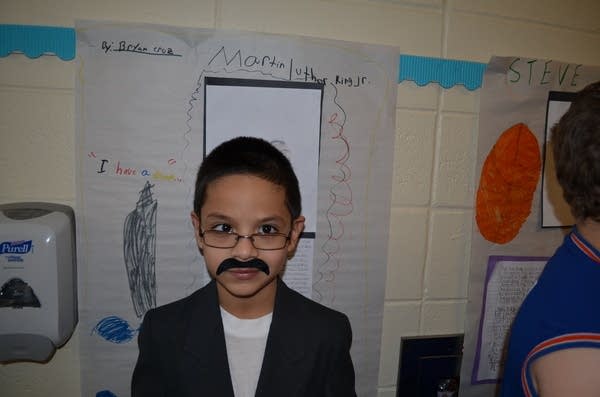

For the biography project, each 3rd grader chose a favorite character or figure from history, did research, wrote an essay and made a poster. Then they held an event for their parents at school. They called it a wax museum.

The kids were dressed in costumes, standing still as statues, until parents went up to them and started asking questions about their characters. The assignment fulfilled the 3rd grade Common Core speaking and listening standards, including “ask and answer questions about information from a speaker” and present information in “diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively and orally.”

The kids loved doing the wax museum, says Glynn. And even more importantly, they loved doing the work that went into putting it all together.

“We had kids who didn’t want to go to recess because they wanted to continue on their biographies,” says Glynn. “That’s what I want to see in teaching.”

He says his students wouldn’t have done either of these projects if they’d been doing test prep.

And the New York Common Core test does not ask students to demonstrate any speaking or listening skills. So if a school were concerned about getting its scores up, there’d be no time to do speaking and listening projects says Glynn.

I want to fix this, not take it down

Kevin Glynn does not want to see the Common Core standards go away, but he thinks they might. There is growing opposition to the standards in New York, much of it fueled by parents who are upset about test prep.

New York officials are responding to the controversy with what Glynn sees as minor policy changes. For example, teachers who score low on the new test-based teacher evaluation system will not face any consequences for at least two years. And standardized testing in grades K-2 has been banned in New York.

But Glynn says there’s a bigger problem that education leaders need to acknowledge: standardized testing has taken over education, he says, and not just in New York, but across the country.

“This culture has become, it’s about a test,” he says. “And we can’t break ourselves away from it, as hard as we try. That’s not the fault of the Common Core, that’s the fault of us as a culture. We have put too much faith in one test.”

Glynn still believes American kids need a challenge; they’re not where they need to be. He thinks the Common Core standards include the kinds of skills and knowledge kids should be learning. But he thinks testing is getting in the way of good teaching.