Career academies: A new twist on vocational ed

Across the country, thousands of high schools are transforming into career academies. The idea is that students will be more engaged if they see how academics are connected to the world of work. And they’ll be more likely to get the postsecondary schooling they need to support themselves in today’s economy.

Connie Majka, director of learning and innovation at Philadelphia Academies Inc., often tells the story of the nation’s first career academy.

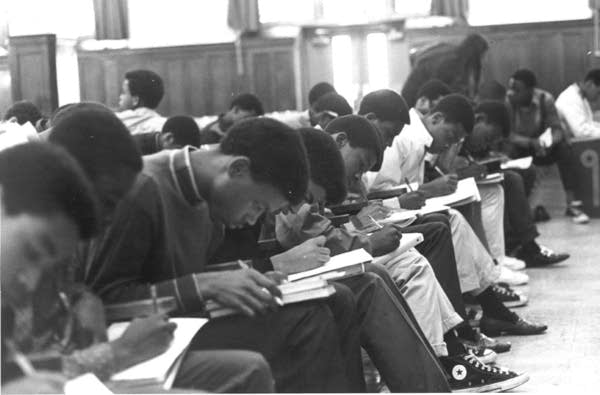

It was 1969, and Philadelphia was in turmoil after years of racial unrest. High schools were segregated. Black students and their allies were protesting discrimination and lack of opportunity.

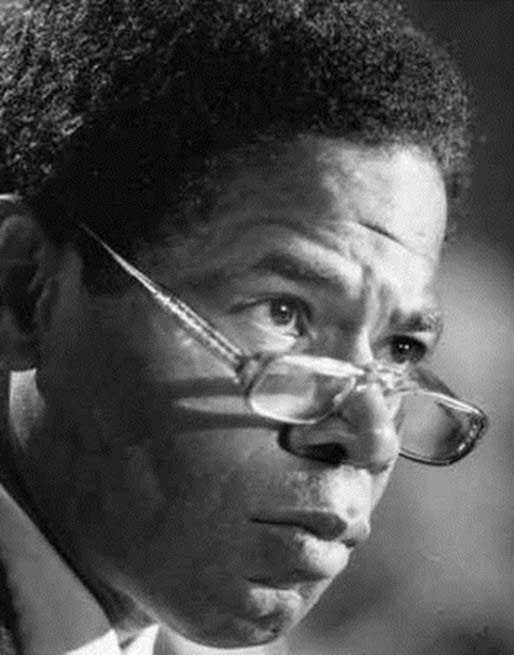

Charles Bowser, the city’s first black deputy mayor, was concerned that “youth were rioting because they couldn’t see a future for themselves,” Majka says. Bowser had an idea. The CEO of the Philadelphia Electric Company liked it, so they brought it to the school with the highest dropout rate in the city. Their idea was to offer the students classes that could lead to jobs repairing electric meters.

But teachers soon realized that they had to back up. Students didn’t know how to read a ruler or the training manuals. So teachers decided to try a blend of academic and vocational training, bringing the career theme into regular classrooms.

“Instead of just math they used electrical math,” Majka says. “Instead of just reading they gave the students electrical manuals to read, so it had a relation to what they were doing.”

Attendance and graduation rates improved dramatically. The Philadelphia school district created a business academy and an automotive academy.

Majka interviewed Bowser shortly before he died in 2010. “I called them ‘academies’ because it sounded special and I wanted the kids to feel like they mattered,” he told her.

Through the ’70s and ’80s, the number of career academies in Philadelphia grew. By 1991, there were programs in 16 high schools. The idea remained the same: to create small schools within large public high schools that would combine academics with career-themed training. Students and teachers would work in small groups over at least two years to create a family-like support system. Connections to the community through employers would expand students’ notion of work and broaden their social networks.

“The trick is not to give them something, but to help them find themselves. If I gave them anything, it was faith in their own potential,” Bowser told Majka.

In 1981, a school district south of San Francisco imported the model. In 1984, the California legislature authorized 10 more academies. They were called the California Partnership Academies, and together with the career academies in Philadelphia, they gave researchers a lot of schools to study. The findings were consistent: Students who attended career academies earned more credits toward graduation, got higher grades and were more likely to stay in school than 10th-12th graders in regular high schools.

In California, subsequent laws have expanded the number of career academies. Today, there are more than 1200 state-supported career academies in nearly 500 California high schools. At least half the students in the academies must be at risk of dropping out in order for the academies to qualify for state funding. At-risk criteria include having a poor attendance record or poor grades, being economically disadvantaged, and being significantly behind in credits.

The most popular career themes are health sciences, arts and entertainment, finance and business, engineering, and public service.

What’s in a Name

Economist David Stern, professor emeritus at Berkeley’s Graduate School of Education, has studied the link between work and school for almost 40 years. He ran the National Center for Research in Vocational Education from 1995 to 2000, when the federal grant that supported it expired. Now he directs the College and Career Academy Support Network, a foundation-funded project that began at UC Berkeley in 1998.

Vocational ed had gotten a bad reputation. When students started getting the message that everyone should go to college, the terminology needed to change.

“Rebranding was because vocational education had come to be known as the non-college option,” Stern says.

In 1998, the American Vocational Association renamed itself the Association for Career and Technical Education.

In 2006, even the language in federal law changed. The Perkins Act eliminated the 90-year-old language that had sent vocational education funding to explicitly non-college-prep programs.

“It took that long,” Stern says, “to espouse the idea that preparation for both college and career can and should be done at the same time.”

By that time, there was ample evidence to support the idea. Research continued to show a significant impact on graduation and attendance, and some papers reported higher grades and better morale in career academies than in regular high schools.

In 2008, a well-respected education and social policy research group called MDRC published a paper that led to an explosion of career academies. Author Jim Kemple says the study began in 1993, when his team was “looking around the country for promising interventions.” He says they wanted to study solutions to the dropout problem that would also help graduates get decent jobs.

Kemple and his colleagues set up a study focused on urban schools made up mostly of low-income African American and Hispanic students. Students applied for a limited number of places in career academies, and were chosen by lottery. The study followed the students for eight years after high school, and compared the students who got into the career academies with the students who didn’t.

Researchers found that students who went to career academies had better jobs and were more likely to be on a career path. It was, as the report said, “strong evidence that career academies produced real improvements in labor market prospects.” The study showed the impact was greater for boys than girls, which was important because boys were more likely to drop out and have trouble finding steady jobs.

The report was published at the same time as the federal government, states and school districts were seeking evidence-based policy ideas to keep American schools competitive with others around the world.

“The career academies were right there,” Kemple says.

Career academies are hot. Experts estimate that at least 6,000 programs call themselves career academies today. But not all of them fit Kemple’s definition of a career academy.

“Even though I think we’re seeing more and more programs calling themselves career academies, I think there are real questions,” he says. He worries about programs that may be career academies in name only because they don’t have three essential components that the research found effective.

“It’s the smaller learning communities, the curriculum that combines academic and career-related coursework, and partnerships with local employers that provide work-based learning opportunities for students,” Kemple says.

David Stern says it’s also important that career academies remain voluntary for both teachers and students. “I’m very reluctant to impose this model anywhere,” he says.

Researchers say as the idea gains traction, it’s an appropriate time for schools and states to experiment with it. Should academies exist alongside other programs in high schools? How do schools decide what career themes get taught? What proportion of high schools in a district should offer academies?

“There are districts trying to push the career and college pathway idea to 100 percent” of their students, Stern says. “Some are going for 80 or 50 percent in districts or schools. We’ll learn from these experiences what a sensible target is. I’m sure it varies from place to place.”

Career Education Transforms a District

In August 2007, the Metropolitan Nashville Public School District was failing. Most of its schools were not making the “adequate yearly progress” required by the No Child Left Behind law. In 2005 the graduation rate was about 60 percent, and achievement scores were terrible.

Flor Romero was a student at Glencliff High School, one of the lowest performing in the district. “I remember one day in English class, two students got in a fight out of nowhere and the teacher got punched,” she says. “I started trying to have friends but most of ’em were like gang-banging and doing lots of crazy stuff.”

Romero says her parents worked a lot and were only vaguely aware of what was going on. All they said was that she had to graduate.

“But they never explained why,” she says. “And it was so funny to me, and I was like, ‘We’re Mexicans; we don’t have to graduate.'”

Flor dropped out after she got pregnant senior year. Now she has two children, ages 8 and 3. She works long hours, including some overnights, helping her mother clean houses and stores. Her dad works in a restaurant. They all live together along with Flor’s husband and her younger sister in a small house near the high school.

Flor’s 16-year-old sister loves school. That’s largely because Glencliff has become a different school. Today, every student there belongs to a career academy. Tonia Romero is a junior in the Academy of Medical Science and Research at Glencliff. The academy has about 300 10th-12th graders in it. Like all the academies in Nashville, it works with employers who offer students internships, field trips and mentoring. The employers also work with teachers at the school to develop career-themed curriculum.

Along the way, students gather tangible skills and credentials. The students wear lab coats in health science classes and learn how to do basic patient care.

“By them teaching us the vital signs, being CPR-certified, it’s a really good way for you to have future plans,” Tonia says. She wants to be an emergency room nurse.

Nashville is betting the future of its schools on motivating students like Tonia. The idea is to bring career education to everybody so that they will finish high school — and go to college, too.

Nashville’s transformation became official in 2010, when Nashville went “wall-to-wall” with career academies in all twelve of its neighborhood high schools. That meant 16,000 students had to choose an academy to join in tenth grade. They took career and technical (CTE) classes along with academic ones. CTE and general education teachers worked together to make sure their classes aligned with career themes.

The transformation has had a dramatic impact on graduation rates. Since Nashville began the career academies, graduation rates at those schools have gone from 57.8 percent to 74.6 percent. Discipline problems have declined. Suspensions rates are down by 30 percent.

Now Nashville is getting national attention for its career academies. President Obama praised the academies in a speech in Nashville in January 2014.

“You’ve made huge strides in helping young people learn the skills they need for a new economy,” he told an audience at McGavock High School. “Skills like problem-solving and critical thinking, science, technology, engineering, math.”

So many educators were visiting the academies that administrators decided it would be less disruptive to convene them all in a conference and take them on tours of the schools.

Connie Majka, with Philadelphia Academies Inc., was among several hundred delegates to the conference in April 2014.

“What is so amazing about Nashville is that they took the model and put it in a system so that it impacts all the students,” she said. “From the crowd here, everybody wants to know how you do it.”

Nashville did it starting with a Small Learning Communities grant in 2004. The federal government made money available to large schools who were experimenting with creating small-school environments within their walls. In Nashville, eight principals worked with a handful of business partners to offer students a chance to learn about the world of work. The students had the opportunity to apply for internships and earn certifications. Attendance, graduation rates and morale started to improve for students in the program. The principals were encouraged to expand the pilot academies. By 2007, when the district was in crisis and the state had deemed it “in need of corrective action,” the academies were its main asset.

“We made a conscious choice here in Nashville to go wall-to-wall with it,” says Jay Steele, the district’s chief academic officer. Steele had run career academies in Jacksonville, Florida, and was recruited in 2009 to take Nashville’s model to scale.

The Nashville Chamber of Commerce was poised to help. It had been publishing an education report card for 20 years, concerned because the reputation of the city is so closely tied to the reputation of its schools. The schools’ poor reputation made it hard for businesses to recruit employees who were parents.

Businesses were also concerned that Nashville graduates were not prepared for the workforce.

“Companies aren’t going to create jobs without anyone with the necessary knowledge and skill to fill them,” says Marc Hill, chief policy officer for the Nashville Chamber of Commerce.

Individual business members of the Chamber had been volunteering in the schools for a long time. But the Chamber made a much bigger investment when the school district decided to transform all of its neighborhood schools.

“What got the Chamber so excited in the academy model is really the scale and boldness, saying 16,000 students and 1,000 teachers need to create this model.” Hill says. “The academy model requires businesses to be involved to be successful. That was a compelling reason for the Chamber to go all-in as a partner.”

Every year, the Chamber has enlisted more business partners for the academies. In 2013-2014, 278 companies and nonprofit organizations were working with one or more of the high schools.

One morning in April, a busload of educators on the Academies of Nashville Study Visit pulled up to Glencliff High School’s front entrance. They were greeted with a chorus of spirited welcomes by the school’s hand-picked ambassadors: 20 or so juniors and seniors wearing blue blazers, white shirts and thin red ties.

Glencliff is one of the most diverse high schools in the country. You could see that when the ambassadors lined up to introduce themselves, and you could hear it in their accents. They had been selected to represent their school at public events and today, they were tour guides. Tonia Romero was one of them.

“We have 46 different nationalities here at Glencliff,” she told her group, “and 26 languages spoken here.”

The student body is about 40 percent Latino and 30 percent African-American. Almost all of the students are from poor or working-class families.

It’s a lot like big public schools in many cities. But it has classes that make it feel not-so-big. Many of those were on display during the tour.

In an advanced design class, groups of three or four students clustered around laptops at a couple of long tables. They were designing little free libraries — basically boxes on poles that will sit in front yards where neighbors can exchange books. In this class, students work together on every aspect of building the library boxes — from design to installation. The idea is that each small group is learning more than engineering. They’re also learning how to collaborate and communicate, solving interpersonal problems as well as technical ones.

The class is part of The Academy of Environmental and Urban Planning (EUP), one of three career academies in this school. The classes EUP offers were developed by the academy’s 10 business partners. The partners include several architecture firms and some environmental nonprofits. In addition to help with curriculum, the business partners send volunteers to work in classrooms and guide after-school programs.

Tara Myers was leaning over to look at designs students had created on their laptops. She is an architect with one of Nashville’s biggest firms, and she asked questions to nudge each group forward.

“Did you come up with a color scheme? Are you going to put it into the model?”

“What are you going to do after the porch element? Which piece are you going to build next?”

“Is that the platform for your roof?”

Myers says her company wants to encourage Glencliff students to choose careers in architecture, construction and engineering. She says across the country, not enough students are choosing to study those fields in college.

“We’re not getting as many graduates coming out of those programs as we maybe did 20 years ago,” Myers says. “We’re also trying to increase the diversity going into those fields as well. More women, more minorities, and we’re really just trying to open that up to a more diverse population.”

At Glencliff, Myers works with the engineering teacher, Adam Guidry. Guidry was a geotechnical engineer who couldn’t find a job during the recession. He’s an energetic 31-year-old, and exudes enthusiasm as he tells visitors on the tour why his advanced design class is so much more than “shop class.”

“The projects that we do are real-world projects,” he says. He says students aren’t just learning to use a miter saw to cut wood. They’re learning to build little libraries.

“That’s SOMETHING,” he says. “That’s not just a skill. There are so many things involved in it.”

EUP students can get certified in AutoCad, a drafting and design software program that’s a building block for an architecture career. The academy also works with Nashville State Community College on a dual enrollment plan that enables high schools students to earn college credits.

“The academy has really pulled me in,” says junior Demari Mumphrey. “I have developed a love for it. It’s like I discovered myself.”

Demari says she used to be an indifferent student. But now she’s fired up.

Demari first learned about engineering and architecture when she was a freshman at Glencliff. Ninth-graders at all Nashville’s neighborhood schools are given the school year to figure out which academy to join. Demari says seeing the wood shop and visiting Tara Myers’ architecture firm clinched her decision.

“We get a look at things that most kids have not had the privilege of looking at,” Demari says.

She was thrilled when she got to spend time job-shadowing at Myers’ firm.

“That was amazing,” she says. “I had never seen an architecture firm. Ever. Just being in that environment was awesome.”

Now Demari knows she wants to be an architect, and she has a plan for how to get there.

“I plan to apply for UT Knoxville,” she says. “And also I would like to go to Rome and study historical architecture.”

Demari says she’s learned from her mother, who supports her and her brother with an $11.50/hour job in a medical billing office.

“As a teenager she didn’t appreciate the privileges she was getting in the education system,” Demari says. Instead, she got pregnant with Demari’s older sister.

“Seeing what she goes through to pay her bills on time, to keep food in the house, it shows me what can happen when you don’t take advantage of the things that you’re given,” Demari says. “When you don’t take education seriously, when you don’t focus on your future, when you don’t focus on gaining knowledge.”

Questions about career academies

Glencliff has two academies in addition to EUP: The Academy of Medical Science and Research has business partners including a chain of dialysis clinics and a medical college. The Ford Academy of Business and Innovation partners with the Ford Motor Company, a credit union and a bank.

The businesses that work with the Nashville academies get a chance to attract and train workers. And the students get field trips, internships, and professionals who help with class projects. They also get a more hands-on way of learning that focuses on projects and career themes. CTE and academic teachers meet regularly to plan curriculum that incorporates those themes. Elizabeth Brewer teaches history in Glencliff’s medical academy.

“We might during our study of world wars talk about how medicine has evolved and battlefield medicine,” Brewer says. “So there are elements of pulling in medical science issues into history and it takes a lot of extra effort because that’s not in the textbook.”

Some teachers say the school doesn’t do enough to support students who are academically oriented. Glencliff offers Advanced Placement classes, but scheduling prevents some students from taking them.

“We focus on minimum proficiency,” says science teacher Hank Cardwell. “We don’t focus on pushing the top.” Cardwell supports the academies, but points out that “things have been lost as well as gained.”

Teachers are also concerned that the academies don’t fit every student’s interests.

“We have a student that wants to be a history teacher,” says history teacher Ashley Walker. “He studies it on his own, and he knows that’s what he wants to do. But he’s forced to choose between business, med science, and engineering. He’s taking these classes that are not of use for what he wants to do with his life.”

At Glencliff, the only options are business, medicine, or engineering. Across town there’s a school that offers alternative energy, education and law. In theory, students are allowed to go to any academy they choose — but the district does not provide busing, so in reality most kids are forced to pick an academy at their local high school.

Nashville’s Chief Academic Officer Jay Steele says any academy, regardless of the theme, will prepare students for the career path they eventually choose.

“It’s not about the content you’re learning and the theme, it’s about the skills you’re learning around the critical thinking, creativity, communication, and collaboration,” Steele says. “Those are the soft skills. Those can be transferrable to any college degree, any career that you want. That’s what’s most important.”

The Chamber of Commerce’s Marc Hill says the academies are a sign that high school education is finally catching up with the modern world economy.

“What were high schools for to begin with? Weren’t they supposed to prepare students for something after they turn 18?'”

Hill says the world has been zooming forward while high schools have stayed pretty much the same. He says career academies are a way to catch students up with advances in technology and give them the “soft skills” they’ll need for both work and college.

“We’ve got to prepare students to thrive in that environment. To adapt, to be creative, work in teams, all the kinds of skills we know they need. Even if they change jobs 20 times, those are the jobs high schools need to prepare them for. … And that means changing the way we educate students.”

Most researchers agree with Hill that high school needs to adapt to new economic realities. And many think it’s appropriate that curriculum be influenced by the local regional economy. After all, that’s where the jobs will be.

“The fact that kids are studying things that are relevant to what the adults in their world do is a nice idea,” says Jeannie Oakes, president-elect of the American Education Research Association.

Oakes is the author of several books about educational disparities. Her specialty is “tracking,” the practice of separating students into different classes or programs based on their perceived academic ability. Her research shows that low-income students of color are more likely to be tracked into vocational programs than wealthier white students are.

And she wonders about the specter of tracking in Nashville, because most students from middle-class families are not attending the career academies.

Instead, they are trying to get into Nashville’s two academic magnet schools. Both academic magnets have been recognized by U.S. News as among the top 100 public high schools in the country, and both have long waiting lists of students hoping to get in. Students have to be academically qualified to get into the magnet schools, and nearly all of the students who attend them go on to four-year colleges.

When the city turned most of its high schools into career academies, it spared the academic magnets.

“Our [neighborhood] schools are just as good as the magnet schools,” says Chief Academic Officer Jay Steele.

But this is so far wishful thinking for the district. Achievement scores are not nearly as good at the neighborhood schools — where the career academies are — as they are at the academic magnets. Graduation rates have risen at the neighborhood schools, but district officials are just beginning to collect data that show how many career academy graduates are going on to college. It’s still too early to say how they do once they get there.

Jesse Register, superintendent of the Metropolitan Nashville Public School District, says in spite of the demand, Nashville has no plans to open more academic magnets.

“The programs are very traditional,” Register says. “They’re very strong but the instructional method doesn’t fit the needs of every student in our district…The academy model really is designed to serve the highest percentage of our population.”

The highest percentage of the population is low-income students. And they do appear to be doing better, overall, than they were before Nashville developed its career academies. But if low-income students are offered different opportunities than middle-class students, it’s a problem, says David Stern, the expert on career academies.

“I think schools should try to level the playing field instead of tilt it,” he says. “If schools are providing advantages to those who are already advantaged, that’s a bad thing.”

Jeannie Oakes says the demographic disparities in who goes to which school could be a sign the district is perpetuating inequality.

“A test for me is: Are the most advantaged families in the community sending their kids to the programs?” she says. “If yes, that’s a healthy sign. If not, I’d want to look carefully.”

Nashville administrators say they are trying to address the disparities problem, not perpetuate it. The career academies help students who might not otherwise go to college plan for postsecondary education. The interpersonal skills they acquire, their new professional networks, and the head start they get in thinking about careers gives them not just the motivation to go to college but preparation they’ll need to succeed there, and even a way to pay for it.

Anamartin Castañeda is a good example. She works fulltime as a patient care technician at Dialysis Clinic Inc., one of Glencliff’s longtime business partners. She started working there when she was a junior at Glencliff.

“When I started the internship I didn’t know anything about dialysis; I didn’t even know it existed,” she says. “So I felt like it opened up a path where I have a job now and I’m good at it.”

Castañeda is 22. She got her patient care certificate at Glencliff’s fledgling medical academy. As a high school graduate with a credential, Castañeda is already doing better than her parents. They came from Mexico and never finished high school. Castañeda is proud to say they’re citizens now. Her dad does yard work and her mom fills orders at an auto parts store.

With help from her employer, Castañeda is going to community college. Dialysis Clinic Incorporated pays most of her tuition, and will continue to support her as she pursues an RN.

Supporters of career academies can point to many stories like Castañeda’s. Research clearly shows that career academies help many students get decent jobs.

Now researchers want to know why. Is it the small school? The project-based learning? The career tie-in? Is one more important than the other? If they can figure out what works, it may be easier to replicate the academies’ success at more schools.

And scholars are still collecting longer-term data about career academies. They want to know how career academy graduates fare later in life, in college and work.