A 21st-century vocational high school

For years, vocational education was seen as a lesser form of schooling, tracking some kids into programs that ended up limiting their future opportunities. Today, in the nation's best vocational programs, things are different.

At Minuteman High School you can learn to be a plumber, an electrician or a cosmetologist. You can also learn environmental science, engineering and computer programming. You can play football, act in the drama club or compete on the math team. You can take Advanced Placement classes, too.

Minuteman is a vocational high school. It’s located in Lexington, Massachusetts, and is one of more than two dozen regional vocational high schools in the state.

Teachers and staff at Minuteman proudly proclaim they work at a “vocational” school. That term has fallen out of favor with many advocates of what is now more commonly referred to as “career and technical” education. “Vocational” is seen as too narrow a term, too focused on preparing students for work rather than higher education. The mantra of the career and technical education movement is that career education in high school is as much a route to college as a traditional academic path.

But whether kids go to college or not, there’s no shame in saying the purpose of education is to get a job, says Michelle Roche, an administrator at Minuteman. The job of educators is to “get people working,” says Roche. “And that’s what we’re doing. We prepare the next generation of workers.”

The enduring debate about the purpose of school

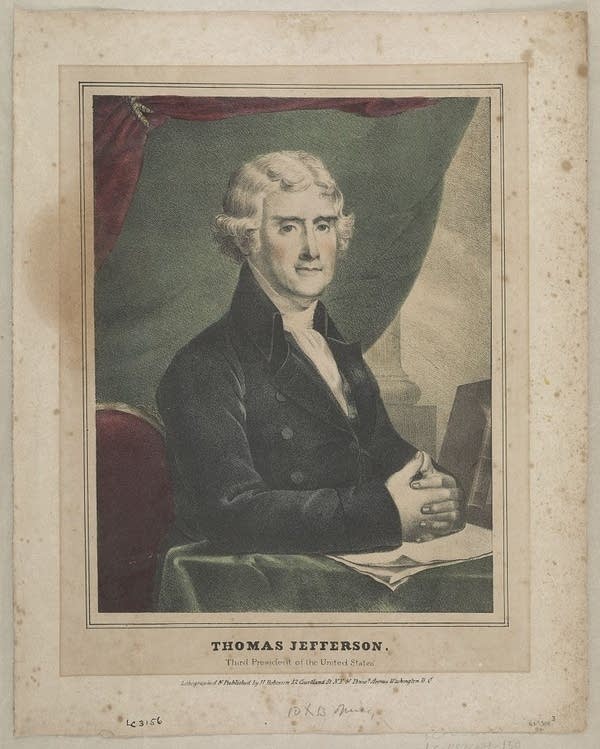

The debate about the purpose of education in America is as old as the nation itself.

Benjamin Franklin argued in favor of a work-focused approach, supporting the idea of apprenticeships and practical instruction. He wanted people to learn skills and trades to help build the new nation.

Thomas Jefferson argued in favor of liberal arts education. He wanted students to learn Greek and Latin, history and science. “For classical learning I have ever been a zealous advocate,” Jefferson wrote.

Jefferson’s view arguably had the stronger influence on the development of American public schools, which have focused more on academics than career training, particularly when compared to many European nations, where career training and apprenticeships tend to play a bigger role. Throughout history, though, there have been many prominent advocates for a more vocational approach in the United States. In 1841, Ralph Waldo Emerson proclaimed that “manual labor” should be “a part of the education of every young man.”

The federal government began funding vocational education in public schools in 1917. By 1982, nearly one in five high school students in the United States took a curriculum that consisted of 25 percent or more vocational classes.

The early 1980s was the high water mark for vocational education, says Richard Arum, a professor at New York University who has studied vocational ed. After that, the programs began to lose support for being “too expensive or too limiting,” says Arum.

Career and technical education tends to cost more than traditional academic instruction, because it typically requires equipment and tools, as well as smaller class sizes. Putting a bunch of kids in rows with a teacher is cheaper than putting them in a machine shop or a drafting studio.

And in the early 1980s, there was growing skepticism about whether spending money to train high school students for careers was a good idea. The economy was changing, manufacturing jobs were beginning to disappear, and many education experts argued that high school should be about preparing kids for college, not work.

There was also widespread concern about whether American schools were doing enough to prepare kids academically. In 1983, the National Commission on Excellence in Education published A Nation at Risk, a report that concluded American students were underachieving academically and failing to keep up with their international peers on tests of math and reading. That report touched off a wave of education reform that was focused mostly on raising academic achievement.

The standards- and test-based reform movement that followed was probably not what Thomas Jefferson had in mind for public education when he argued for a “classical” approach, but it was closer to his vision than the vocational approach Franklin and Emerson advocated.

In recent years, the focus on academics in American education has gotten stronger. The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 created incentives for schools to spend even more time on math and reading, edging out time for other subjects, including vocational classes. The share of high school graduates in the United States whose curriculum consisted of 25 percent or more career and technical education courses dropped from nearly 20 percent in 1982 to just 6 percent in 2004. (Read more about the history of vocational education and the debate about “tracking.”)

College for all

The goal in most American high schools today is to prepare all kids for college.

“It’s basically a one-size-fits-all model,” says Bill Symonds, a former education correspondent for Businessweek. “The model is that you take a college prep program of study, go off to a four-year college, and get your degree.”

Symonds says the “college for all” model has “been embraced overwhelmingly by Americans.” But it’s not working for most young people, he says.

“The reality is that by the time they get to their late 20s, only 30 percent of young people have actually gotten a four-year degree,” says Symonds. “So you’ve got a paradigm that’s embraced by almost everybody, but only 30 percent are getting there.”

Symonds is co-author of a 2011 report for the Harvard Graduate School of Education called Pathways to Prosperity. The report argues the United States is failing to prepare millions of young people to lead successful lives because high schools focus too narrowly on an academic, college-prep approach to education.

Symonds points to labor market data that show most jobs don’t require a bachelor’s degree. According to the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, there will be an estimated 55 million job openings in the American economy through 2020, and almost a third of those jobs will go to people with an associate’s degree, some college or an occupational certificate. (More than a third of jobs will require no education beyond high school, but those are mostly low-skill, low-wage jobs).

Many of the jobs that require certificates will be in what experts call “middle-skill” occupations, such as construction manager, electrician and computer technician. These jobs pay relatively well. In fact, by skipping college and getting a certificate instead, it’s possible to earn more than someone with a degree. About a third of people with just a certificate make more than the average person with a college degree. Employers consistently report that middle-skill jobs are hard to fill because of a shortage of workers with the right training.

Given all this, Symonds says it’s a mistake to put so much emphasis on getting everyone to college. He says career and technical education needs to make a comeback in American high schools. He says not only can career focused education help students gain the kinds of technical skills employers are looking for, but it can help more kids get through high school.

“Every year, some one million students leave before earning a high school degree,” writes Symonds in Pathways to Prosperity. “Many drop out because they struggle academically. But large numbers say they dropped out because they felt their classes were not interesting, and that high school was unrelentingly boring. In other words, they didn’t believe high school was relevant, or providing a pathway to achieving their dreams.”

Symonds says career and technical education can help students become more engaged in school, and give them a wider range of options when they graduate — including going on to college.

Symonds points to Minuteman High School in Massachusetts as an example of what good career and technical education looks like. And he points to his own son, Chris, as an example of what this kind of education can do for kids.

‘I just felt so stupid’

For as long as he can remember, Chris Symonds was interested in food and cooking.

“Weekends were filled with my dad cooking,” he says. “I just enjoyed it. I found it the coolest thing.”

When he was 9, Chris made his first meal. It was a mussels dish with white wine and peppers.

“Everybody liked it,” he says. When you make a meal that people enjoy, “you can feel good about yourself,” says Chris.

This was a big contrast with the way he felt in school.

“I found myself learning slower than everybody else and I just felt so stupid,” he says.

Chris grew up in Weston, Massachusetts, an affluent town full of academic high achievers. By middle school, he was really struggling.

“I had C minuses,” he says.

Chris knew things were going to get tougher in high school, and he wasn’t sure he would make it to graduation.

His dad, Bill Symonds, says there are millions of kids like his son Chris.

“They may be having a hard time with math or English or some of the other subjects,” Symonds says. “Because of that, they’re getting very negative messages. ‘You’re a struggling student, a failing student. You’re going to be a loser, and if you don’t turn this around, you’re never going to make it.'”

Symonds thought his son needed a chance to be good at something in school. But at the local high school, “there wasn’t a single course that would really prepare him for a career in cooking,” says Symonds. “It just wasn’t offered. All of that had been eliminated from the curriculum.”

Students in Massachusetts whose home schools don’t offer the career and technical training they’re interested in have the option of choosing a regional vocational high school. Minuteman serves students from 50 public school systems in the suburbs of Boston. Some kids travel more than an hour each way to get to school.

Symonds says for a lot students, especially in the wealthy, well-educated Boston suburbs, choosing vocational school can be a hard sell to parents, and to teachers and guidance counselors at their home schools as well.

“There is a tremendous bias against this kind of education,” says Symonds.

People told Chris “he would be throwing his life away” if he chose Minuteman, Symonds says. They assumed it meant he’d never go to college, never amount to much.

But Chris knew it was the right choice for him.

“I didn’t want to fail out of school,” he says. “I wanted a future.”

And he knew his future was cooking.

Figuring out what you want to do

Chris Symonds knew exactly what he wanted to study at Minuteman. But that’s not true for all kids. Some choose Minuteman in order to figure it out.

When Kendra started at Minuteman, she says she had no idea what she wanted to do. “I was like, I’m not good at anything,” she says.

All freshmen have to take what’s called “Freshman Career Exploratory.” They spend a few days in each major, or “shop.” There are 20 different majors at Minuteman. Kendra says she knew right away that she liked environmental science and technology.

“I’m not a tree hugger, but it fit me so well,” she says.

Kendra likes all the hands-on work in the lab, and getting a chance to go outside a lot is a bonus. She says coming to Minuteman helped her realize she has “a passion for something.”

Kendra was never that into the academic part of school. She says she had terrible grades in elementary and middle school.

But at Minuteman, she’s on the honor roll.

She attributes that in part to the way the schedule works at Minuteman. Students spend one week in academic classes, the next week in their vocational classes. School was exhausting and tedious when it was all academics, all the time, says Kendra.

“You go home and every day you have a stack of homework to do,” she says.

But at Minuteman, every other week, “you can just do what you love.” She can get through math and English one week knowing she’s got environmental science to look forward to the next.

Kendra is now a senior at Minuteman, and she knows exactly what she wants to do with her life. She plans to work with marine mammals, helping to rescue them when they are sick or stranded and then rehabilitate them to the wild. She is going to Unity College in Maine, on a scholarship, to double major in marine biology and captive wildlife care.

One of the advantages of career and technical education in high school, according to advocates, is that kids get a chance to figure out what they’re interested in before they go to college.

But at Minuteman, the goal is not to get everyone to college. The goal is to give kids good options after high school. Steve, a senior in the electrical wiring program, says he choose Minuteman because he “didn’t want to get out of high school and not know what I was going to do with my life.”

Steve will graduate with a high school diploma and a certificate that can get him started as an electrician’s apprentice. If he becomes a certified electrician, he can expect to make about $40,000 a year to start. That’s higher than the median wage for all workers in the United States. And a college degree isn’t necessary.

Integrating academics and technical training

Students at Minuteman spend every other week in traditional academic courses. But they also get academic instruction in their vocational classes. This is a big change from the way things were when Al St. George, one of the instructors in the electrical wiring shop, went to vocational school. He graduated in 1975, and says back then, vocational instruction was “all just hands-on.”

Now, he says, vocational education is about integrating academics into career training. For example, one of the projects students in electrical wiring do involves calculating the wattage of a circuit using Ohm’s Law. Ohm’s Law states that the current through a conductor between two points is directly proportional to the potential difference across the two points.

To be an electrician you have to know this, says St. George. But when he was in school, instructors just taught him how to make the calculation; they didn’t explain the law or talk about its significance and how it relates to the physics of electricity. Now instructors do this. Vocational education has “changed for the better,” says St. George.

-Nijan Datar

Another benefit of career education is the chance for students in academic classes to see how theory can be applied in the real world. When the students in his physics class are learning about gear ratios, teacher Eric Marshall brings them to the Minuteman auto repair shop where the automotive instructor shows them different gears and how they work. The students get to pick up the gears, fiddle with them, watch them move.

Marshall says it’s hard for students to make the conceptual leap between calculating gear ratios in the classroom and understanding “what’s actually making your car drive.” When they go to the auto shop and see the gears move, many of the students get it for the first time, says Marshall. “They actually get excited about physics!” he says with a grin.

Success breeds success

Chris Symonds, the aspiring chef, says when he was in middle school he was constantly asking himself, “Why am I learning this?”

But once he got to Minuteman, he started to see why he needed to learn math and English. Chris is now a senior, about to graduate in the top 10 percent of his class.

“In culinary arts, there’s not just the side of, ‘Make this recipe and put it out,'” he says. “There’s the side of, multiply this recipe. Break it down. Make more, make less. There’s the side of hospitality, and learning how to write out business plans, pay wages, make a profit.”

He says the academics seemed worth learning when he realized he needed those skills to be a successful chef.

Michelle Roche, the director of career and technical education at Minuteman, says students at Minuteman make academic turnarounds like Chris’ all the time.

“The students who have not felt success when they’re in a traditional academic school, where they’ve got to sit, the teacher’s talking at them, they’ve got to regurgitate this information, they’ve got to memorize and study. They’ll come here and they’re standing on their feet, they’re working with their hands, they figure out a problem,” she says. “And success breeds success.”

Ninety-five percent of students at Minuteman scored proficient on the state English test in 2013, better than the state average. Seventy percent scored proficient on the state math test, 10 points below the state average. But it’s significant to note that Minuteman serves a higher percentage of special education students than other high schools; nearly half of the students at Minuteman have some kind of learning or other disability.

For staff and teachers at Minuteman, good test scores are validation that they’re doing something right. But they say test scores are not the true measure of success. It’s what students are able to do in the real world.

For Chris Symonds, that means working at Blue Ginger, one of the top restaurants in the Boston area. He started as an intern, but by the end of his senior year of high school, Chris was a paid employee, responsible for the daily staff meal and helping out on the line during dinner.

Chris is the first high school student who’s ever worked at Blue Ginger, says executive chef Jon Taylor.

“I actually have a little soft spot for him,” says Taylor. “I did vocational school myself.”

Taylor says one of the things be appreciates most about Chris is his work ethic. “He puts his head down and works,” says Taylor. “I can tell his drive. And passion is what this business is all about.”

Taylor says after he graduated from vocational high school, he never gave college much thought. He says cooking is one of those careers you can learn on the job.

But Chris Symonds is taking a different path. After high school graduation, he’s heading to the Culinary Institute of America, one of the best cooking schools in the world. His coursework there will include math and literature, and he’ll finish with a bachelor’s degree.

For Chris, vocational education was a way to get to higher education when he otherwise might not have made it through high school. And even for academic high achievers, vocational education may be a better way to get to college.

A better path to college

Brandon Datar is a senior in the environmental science and technology program at Minuteman High School. His younger brother Sean is a freshman in the robotics program.

The Datar brothers went to private school until 8th grade. Their dad is an electrical engineer and their mom teaches at a Montessori school. They’re probably not the kinds of kids you’d imagine at a vocational high school.

But when Brandon was looking at options for high school, Minuteman stood out, says his dad, Nijan Datar.

“Being an engineer myself, I like the fact that schools like this cater to making an actual living,” he says.

The family had been touring public and private high schools in the Boston suburbs, many of them considered among the best high schools in the country. But Nijan wasn’t impressed. He says the main goal seemed to be getting students into the best, and most expensive, colleges. But no one seemed to be talking about what kids were going to do with their college degrees once they got them.

-Alice Ofria

His wife Teresa Datar says high school students need more direction.

“My feeling is that in many high schools, students don’t know why they’re in the classes that they’re in. They’re just kind of biding time,” she says. “And then they go off to college and they flounder.”

Her son Sean did not want that to happen to him. He says what he liked best when he toured Minuteman is that the students he met seemed to have a plan for their lives.

“When you think about it, you want to know what you want to do, and you want to be sure of it, by the time you go to college,” says Sean. “You don’t want to pick a major, get like $50,000 in debt,” and then realize you want to do something else.

Ed Bouquillon, the superintendent of the school district where Minuteman is located, says one goal of vocational education is to help kids figure out what they don’t want to do.

“Sometimes I’ll have kids who, at the end of their four years, they’ll say, ‘Dr. B, you know, I came here in nursing and I really don’t like it.’ And that’s a valuable thing to know,” says Bouquillon. Better to figure it out in a public high school, where you’re not paying tuition, than at a college that’s charging you thousands of dollars, he says.

But students and families who choose vocational education face stereotypes. Nijan Datar says friends and neighbors in their affluent Boston suburb were kind of startled when they heard his son Brandon was going to Minuteman.

“What we did was definitely not the norm here,” says Nijan. “I have had raised-eyebrow looks. It’s almost like you can read that other person’s mind thinking, OK, the reason I did this is because my son is not very smart.”

But Nijan says his family chose Minuteman because it seemed like a better path to college than a traditional high school. His sons are “going to a regular high school but also dipping [their] feet into the real world and starting to get an understanding of what it takes to get a job,” he says.

One thing he wasn’t prepared for when his kids went to Minuteman is that they might like traditional trades that don’t require a college degree. When Brandon came home from the exploratory program freshman year and announced that he liked plumbing and welding, Nijan was taken aback.

There’s a lot of money in the traditional trades, Nijan acknowledges. “But I wanted him to go to college.”

And Brandon is going to college. He’s heading to the Colorado School of Mines to get a bachelor’s degree in geological engineering. But if he wanted to get a good job right out of high school, he probably could. Every Minuteman student is supposed to graduate with some kind of certificate or license. Brandon has a wastewater treatment plant operator’s license and a drinking water license plus two certificates in occupational health and safety administration.

“I’ve gotten all kinds of things out of my education at Minuteman that kids at other high schools don’t get,” he says.

After Minuteman

Alice Ofria graduated from Minuteman in 2009. She majored in environmental science. Now she works as a lab technician for the town of Billerica’s drinking water department.

It started as an internship, the summer after she graduated from Minuteman. But she was so good at the job, the town hired her on as a permanent employee, says John Sullivan, her boss.

“She’s an expert in computers and a whiz in chemistry,” says Sullivan.

Sullivan says it’s hard for the town to find people with Alice’s skills. There’s a “chasm” between what people learn in school and what’s needed in the “real world,” says Sullivan. Even college graduates don’t tend to have the needed mix of skills and knowledge.

But Alice was ready to go from day one, he says.

“The program at Minuteman prepared her to actually learn” what she needed to on the job, and fast. “She’s done outstanding work here,” he says.

As a lab technician for the town, Alice makes almost $28 an hour. She gets health and retirement benefits too. Her friends are amazed.

“Most of my friends are waitresses or work as a secretary somewhere, or at a tanning salon,” she says. Some of them are struggling to get by. But Alice is doing great. She just bought a new truck and went on a vacation to Puerto Rico.

And she’s working just 25 hours a week. That’s because she’s also a full-time college student at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, where she is working on a bachelor’s degree in environmental science.

“People in my college classes don’t know things I know, that I learned from Minuteman,” Alice says. “It feels like I’m ahead of everybody.”

Her boss, John Sullivan, is the treatment chemist for the town of Billerica. He’s planning to retire soon, and he’s hoping Alice will take his job.

But Alice isn’t sure yet what she wants to do.

“There’s a very wide range of jobs I could get,” she says. “Working here is one, or a wastewater job. I could work at a site that had a hazardous spill. They’re doing a lot of fracking. I could go and work there.”

Alice always knew she wanted to go to college, but says there are a lot of good jobs she could get using just the skills and experience she gained in high school.

“Vocational school is where it’s at, to put it bluntly,” she says. “Because no one experienced a field, a trade and also got the same [academic] education. None of my friends experienced that, except for the friends I went to [Minuteman] with.”

Skipping college

When she was in middle school, Liz King decided she wanted to be a hairdresser.

“I always fiddled with hair,” she says. “Not that I was any good. If you see pictures of me in middle school, I looked like a wreck!”

Doing hair is what she loved. She did not like school.

“I am not a book person,” she says. “You just know you are or you’re not.”

She grew up around of lot of bookish types. Almost all of the graduates of her local high school, Lexington High, go on to four-year colleges.

“Full of Harvard types,” is the way Liz describes Lexington High School. “If you’re a genius or if you have strong special needs,” you’ll do fine there, she says. “But anybody that’s in the middle, like me, I would have got lost there.”

At the end of 8th grade, Liz told her mom she wanted to go to Minuteman and study cosmetology.

“I wasn’t having any of that,” says Liz’s mom, Jeanette Chapman.

Years earlier, her son had asked if he could go to Minuteman, to study plumbing. She said no to him too.

“I just had the impression that going to vocational school, he would miss out on something, a profession where you could make more money,” Chapman says. “I think it was all to do with making more money.”

But Liz is a persistent person. She begged her mom to let her go to Minuteman.

Finally, her mom relented — under one condition.

“I told her that I wanted her to do the college prep classes,” Chapman says. “To give her the opportunity to go on to college, if she desired.”

Liz went to Minuteman and did all the college prep classes, but says there was no way she was going to college.

“I thought that if I went to college, I would waste a crapload of money,” she says. “I knew I wasn’t good at studying. I was a procrastinator. And if someone was like, ‘Hey Liz, let’s go party, hey Liz, let’s go NOT study,’ I would’ve been like. ‘OK!’ I’m not self-motivated like that.”

But she is motivated about her career in cosmetology.

Liz graduated from Minuteman in 2004. By then, she had completed enough training hours in school to take the exam for her cosmetology license. She took the test days after she finished her high school classes and had her license by the time she walked across the stage to get her Minuteman diploma.

“My thing was having my certification before I walked,” she says. “That was more important to me than my diploma.”

Liz has been working as a cosmetologist ever since. “I’ve had my hands on hair since I was 14!” she says. “Not too many hairdressers can say that.”

Liz is now 28. She’s married and has a 10-month-old baby, and recently, she and a business partner opened their own hair salon. It’s called J&L Studio, in Arlington, Massachusetts.

On a Saturday in March, it was crowded with clients. One of them, a woman named Sandy, says she’s been following Liz from salon to salon for years.

“She’s the best,” says Sandy.

Liz says business at J&L Hair Studio is good. She’s not willing to say how much money she and her partner are making, but she says it’s enough.

“We’re good, we’re comfortable, we’re paying our bills,” she says.

Money has never been the driving force behind Liz’s choice of occupation. She’s a hairdresser because that’s what she’s wanted to do, since she was a kid She thinks people who say everyone has to go to college are “uninformed and closed-minded.”

“I know people around here look down on me because I don’t have a college degree,” she says, referring to people in the highly educated Boston suburbs where she lives and works. But she doesn’t care.

I’m blue collar “and proud of it!” she says.

Liz says when it’s time for her daughter to look at high schools she plans to take her to Minuteman.

“Who knows, she might be book smart and want to be a doctor and then I don’t know if Minuteman would be the right choice for her,” she says. “Maybe she would need like a Harvard-type high school. But I want her to know that it’s not one way or no way.”

As for Liz’s mom, Jeanette Chapman, she’s proud of her daughter. She can see that vocational high school was the right choice for her, and thinks maybe that’s what her son should have done too.

After she told him he couldn’t go to Minuteman to study plumbing, he went to Lexington High. He graduated, went off to college, quit before finishing his degree, and got a job with a plumbing company.

“And my son is now a plumber!” Chapman says, shaking her head in disbelief.

She says it’s worked out well for him. “He’s been with the same company since 1998,” she says. “He’s very happy.”

But she still wonders if her kids might someday need college degrees. She thinks Liz could benefit from business classes, for example.

Liz disagrees. She says she’s learning what she needs to on the job, and she has no interest in spending time or money on a degree.

That doesn’t mean her education is over, though. Liz often goes to trainings to learn more about hair. And she still hates learning from books. She says other cosmetologists at the trainings do too.

“When we go to classes as hairdressers, [the] educators know that,” she says. “You have a little bit of time to flip through paperwork with these people but the hairdressers are like, ‘What the hell? When’s break? When’s lunch? Can we get to the hands-on part?’ That’s the creatures that we are,” says Liz. “Can’t read and learn. Just can’t. It’s hard. Really, really hard.”

But she still has to do it sometimes. In fact, right now she’s studying for a big exam to get a board certification in hair coloring. It’s going to be a challenge, but she thinks she’ll pass. One of the things she learned in all those college-prep classes at Minuteman is that she can do it if she has to.

What do I love to do?

Ed Bouquillon, the superintendent of the school district where Minuteman is located, says when students graduate from Minuteman he wants them to be able to answer two questions: What do I do well? And what do I love to do?

“And we’ll connect the answers to occupations or college majors,” he says.

When he meets with parents, he asks them if they know the answers to those two questions.

“Some say ‘yeah,” he says. “And some say, ‘Boy, I wish someone had asked me that.'” They aren’t doing what they love at work, and they wish they were.

Bouquillon says bringing more career and technical education into American high schools can help kids make better decisions about their futures. He thinks the debate about whether school should focus on career skills or academics is ridiculous.

“It has to be both,” he says.