The history of HBCUs in America

Zach Hubert came out of slavery with an adage that he would pass on to his children, and his children's children, and their children down the line. "Get your education," he would always say to them when his family gathered together in later years. "It's the one thing they can't take away from you."

This essay is part of the larger radio documentary The Living Legacy: Black Colleges in the 21st Century, which you can listen to in its entirety on this website or on our podcast feed (iTunes).

***

Zach Hubert came out of slavery with an adage that he would pass on to his children, and his children’s children, and their children down the line.

“Get your education,” he would always say to them when his family gathered together in later years. “It’s the one thing they can’t take away from you.”

Zach grew up a slave on the Hubert plantation in Georgia’s Warren County. Most slaves on the plantation were forbidden to have books, but Zach was the same age as the plantation owner’s son, and the boy taught Zach how to read.

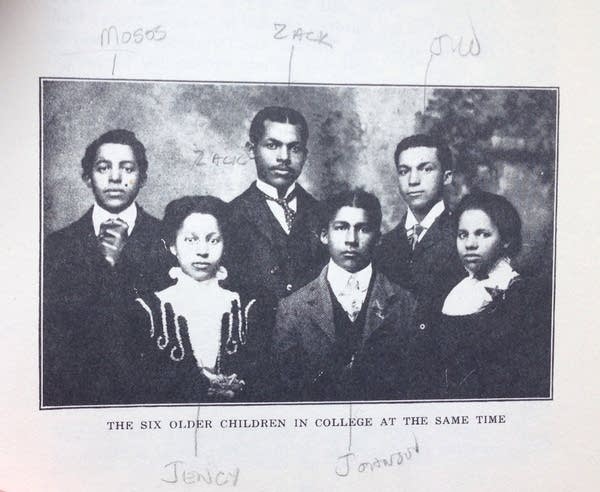

When freedom came to Georgia, Zach and his wife rented a farm and worked until they saved enough money to buy some land. They had 12 children, seven boys and five girls, and Zach set up a school and hired a teacher to educate them.

When they came of age, those children did something that would have been unthinkable for Zach and his peers.

They went to college.

A paltry handful of traditionally white colleges accepted black applicants in the first part of the 19th century. And three colleges, two in Pennsylvania and one in Ohio, educated mostly black students in the mid-1800s.

But after the Civil War, African American education blossomed. Black ministers and white philanthropists established schools all across the South to educate freed slaves. These schools, more than 100 of which are still open today, became known as historically black colleges and universities, or HBCUs.

“They started in church basements, they started in old schoolhouses, they started in people’s homes,” says Marybeth Gasman, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania who studies HBCUs. “[Former slaves] were hungry for learning … because of course, education had been kept from them.”

Initially, many schools were designed to provide just basic primary and secondary education.

“The prospect was for there to be more teachers, preachers and farmers,” says Jarrett Carter, an HBCU graduate and journalist, who covers black colleges on his website HBCU Digest. “In the years since their establishment, you saw schools that evolved by their own hard work to now you can go be an engineer, a physician, a lawyer, a legislator, a college president.”

In the 1890s the second Morrill Land-Grant Act specified that states using federal higher education funds must provide an education to black students, either by opening the doors of their public universities to African Americans, or by establishing schools specifically to serve them.

Rather than integrate their public institutions, many Southern states created a completely separate set of institutions serving African Americans. Thus were born many of the South’s public black colleges.

–Zach Hubert, former slave

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, black colleges thrived. They attracted top black students — the best and the brightest. Howard, Morehouse, Spelman, Tuskegee — these schools and others like them trained the lion’s share of the nation’s black doctors, lawyers, dentists, teachers and other professionals. “The golden age,” Howard archivist Clifford Muse calls it, because “when segregation was rampant some of the most brilliant black educators had to come to [black colleges] in order to have an opportunity to teach. They couldn’t go any place else.”

Even today, HBCUs may be over-performing in producing certain kinds of graduates. Though black schools represent a tiny percentage of American colleges — around 3 percent of schools – they produce 24 percent of black STEM grads and confer almost 35 percent of all bachelor’s degrees earned by black graduates in astronomy, biology, chemistry, math, and physics. According to a report from the National Science Foundation, eight of the top 10 institutions producing black undergrads who went on to earn science and engineering doctorates were HBCUs.

“If we didn’t have black colleges, we would have almost no African Americans in the sciences,” Gasman says. “We wouldn’t have any in technology. We’d have very, very few black doctors. We’d have very few black dentists, almost no black people in computer science …. We would take a hit in terms of African Americans in all of these different fields. I think that’s not a hit I want to see.”

Which would you rather have: a diploma from St. Paul’s or UVA?

The last president of St. Paul’s College sits down heavily behind his burnished desk. His knee has been acting up; getting in and out of chairs is difficult.

“Each day I walk into this office, I sit behind a desk and I look at stuff,” he says. “I see no reason for it to close. Absolutely no reason.”

Millard “Pete” Stith has a curious job for a college president: not to build his school up, but to dismantle it gently, with as much order and as little destruction as possible.

St. Paul’s College founder James Solomon Russell was born three years before slavery ended. He became an Episcopal priest and came to this rural region of southern Virginia in 1882 to start churches and a school to educate newly freed blacks. Locals warned him that the Ku Klux Klan had torched a similar school in North Carolina and so Russell waited until 1888 to establish St. Paul’s Normal and Industrial School.

St. Paul’s trained black students in the trades: brick making and welding for the men, tailoring and home economics for the women. Later it branched into liberal arts education.

But while St. Paul’s survived the ravages of the Ku Klux Klan and rampant discrimination, it couldn’t survive integration.

As traditionally white schools in the area opened their doors to black students, enrollment at St. Paul’s dwindled.

“What diploma do you want hanging on your wall?” Stith asks. “UVA or St. Paul’s?”

St. Paul’s administrators tried to keep up. They built a 500-seat auditorium with a baby grand piano, and a student union with a three-lane bowling alley.

But it wasn’t enough. Enrollment kept falling; debts piled up. The school lost its accreditation, which meant that it was no longer eligible for state or federal financial aid.

In 2013 St. Paul’s graduated about 55 students, and shut its doors. Now the whole campus — 135 acres, 31 buildings, all the furniture, and even the baby grand piano — is up for sale for $2.8 million.

“In 1888 there probably were pockets of slavery still going on and [Russell] founded this school in the midst of all of that,” Stith says. He shakes his head. “He had real threats. And he kept it open. And that’s a shame to bring this great experience to an end. It’s almost criminal.”

In the past three decades, five HBCUs have closed their doors. Many more are on academic probation or have lost their accreditation.

“I would say out of 105, there’s about 15 of them that are in pretty bad trouble,” says Marybeth Gasman. “They’re having a very difficult time.”

Gasman does not like the narrative that HBCUs are doomed. She says, with a heavy dose of sarcasm, that she’s used to people calling her up to ask if “black colleges are at the crossroads.” And she notes that colleges of all kinds are struggling to stay afloat. Higher education can be a brutal marketplace.

But Gasman does think that the headwinds that batter HBCUs are uniquely fierce.

“It’s more volatile for black colleges,” she says. “I think it’s more volatile because they have to deal with racism, people don’t think that they should exist. People start to say, “Why do we need these institutions [when] black people can go to majority institutions?””

Before higher education was desegregated in the 1950s and 60s, almost all black college students enrolled at HBCUs. Today, only about 8 percent of black college students do. It’s important to note, says Gasman, that the number of students at black colleges in the aggregate isn’t dropping. In fact, HBCU enrollment has actually increased slightly since 2000, by about 10 percent.

But in the same time period, African American enrollment across the higher education landscape as a whole increased 80 percent.

“The numbers are still up [at HBCUs], but the type of student is changing,” Gasman says. “Historically black colleges used to have overwhelming numbers of middle class students, highly prepared students, and then their makeup changed. Now you have a big mix. You have affluent students, highly prepared students, you have middle income students, mid range preparation, and you have low income and you have very little preparation.”

Earl Richardson presided over this trend firsthand over the 25 years he served as president of Morgan State University. As historically white institutions came under pressure to enroll black students, “they began to cream off our better students,” he says. “There’s been slippage in the preparedness level of our students on average.”

Lower preparedness levels hurt graduation rates, and graduation rates at historically black colleges are low, averaging just 30 percent. That number is troubling, on its face. But Jarrett Carter says it reflects the type of student that HBCUs often educate: low income, first generation, underprepared.

“You have to give some credit for colleges which are willing to do what secondary schools and systems won’t do,” he says. “Isn’t it interesting that schools that are designed to reverse engineer everything you don’t do from pre-K through 12 and fix that situation are now being regarded as failures?”

It’s a vicious cycle: Poorly prepared students lead to low graduation rates; low graduation rates make state governments and other investors reluctant to inject money into the schools; cash-strapped HBCUs have inferior facilities and underpaid faculty; this gives the impression that they are dysfunctional institutions, and makes lawmakers and alumni more reluctant to invest.

Marybeth Gasman’s research points to a consistent underfunding of public HBCUs by states, which prioritize flagship universities and other traditionally white schools in public systems. In recent years public HBCUs in Maryland, Mississippi and Alabama have sued their states for more equitable funding. And at both public and private HBCUs, donations are much lower than at their traditionally white counterparts. In 2009 the average endowment for public HBCUs was $49.3 million, compared to $87.7 million at public schools in general. For private colleges, the average HBCU endowment was $38 million, compared to $223 million for the sector as a whole.

HBCU Digest founder Jarrett Carter says that HBCUs themselves, founded as they were to provide options to people barred from other schools, were a symptom of racism; their funding situation today is another symptom of the same.

“The only way you cure [the problem] is to make black institutions look like white institutions, and that’s totally uncomfortable for people,” he says. “That’s the fight we’re now having in 2015, and I’m hoping it’s not too late.”

One note of disclosure: Historian Marybeth Gasman, who appears in this story, receives funding from the Lumina Foundation. And so does American Radioworks.