Rethinking teacher preparation

In the United States, teaching isn't treated as a profession that requires extensive training like law or medicine. Teaching is seen as something you can figure out on your own, if you have a natural gift for it. But looking for gifted people won't work to fill the nation's classrooms with teachers who know what they're doing.

Deborah Loewenberg Ball used to be an elementary school teacher. She was really good at it.

“You’re just such a natural teacher,” people told her.

She didn’t see it that way, though. Teaching was something she was working hard at.

But Ball says the idea that some people are just born to be teachers, that the skill of good teaching is some kind of inborn trait, runs deep in American culture.

And she says there’s this other idea that runs pretty deep too. It goes like this: “Teaching is pretty easy,” she says. “I mean, it’s little kids, or even high school kids. The content is not that hard.” Anyone with a college degree who likes kids can be a teacher. That’s the belief.

But Ball didn’t find teaching easy. What she was figuring out is that teaching requires a special set of skills. There’s knowing math, and there’s knowing how to teach math. They’re not the same thing. (Watch a video of Ball talking about this.)

And knowing how to teach math doesn’t come naturally.

“Teaching is complex work that people actually have to be taught to do,” she says.

But in the United States we haven’t treated teaching as a profession that requires extensive training like law or medicine, she says. Teaching is seen as something you kind of figure out on your own; it’s more about personality than skill. People with a gift for teaching, the thinking goes, will bloom into great teachers and the way to improve education is to recruit more of these talented people.

That is not the way to fill classrooms with teachers who know what they’re doing, says Ball. Teaching is one of the largest occupations out there. There are 3.5 million teachers in the United States.

“Clearly there are people who figure out how to do this either passably well or very well,” she says. “But lots and lots and lots of people do not.”

Ball is now dean of the School of Education at the University of Michigan. She says teacher training in the United States needs to dramatically change.

People who want to be teachers “deserve to learn how to do this work well,” she says. “And the children that they teach particularly deserve to have those teachers taught.”

The Problem with Teacher Preparation

There are basically two kinds of teacher preparation in the United States.

There are “traditional” programs based at colleges and universities. You typically take a few semesters of education classes as part of a degree program, do some student teaching, and then get certified to be a teacher. Traditional programs have long had a reputation for being easy to get into, and easy to complete.

There are also “nontraditional” programs. Those are a more recent invention. Teach for America is probably the best known. The idea is to recruit smart people from top colleges and bypass a lot of the coursework that is required in traditional programs. Instead, you get a brief introduction to teaching and you’re in the classroom pretty much right away.

–Jennifer Green

There are more than 2000 of these traditional and nontraditional teacher preparation programs in the United States. Sounds like there’s a lot of variety out there. But when I ask teachers if they felt prepared to teach, there’s not a lot of variety in the response.

“No, no, no, no!” says Jasmine Bankhead, emphatically, looking at me like I’d just asked her a stupid question. Of course I wasn’t prepared! That’s practically a given among American teachers.

Bankhead went to a traditional teacher prep program in the early 2000s. She took about a year’s worth of coursework. It was pretty general.

She was expecting to learn a lot when she did her student teaching. But on her first day, she says, “my mentor teacher, she came in, we talked for a few minutes, and she was like, ‘OK, I’ll be in the library from now on.’ And just like that, I was by myself. And although I complained a little bit to my student teaching supervisor, I still felt like I was expected to make it work.”

You hear that line a lot from teachers. I was just expected to make it work.

Jennifer Green did a nontraditional program back in the 1990s. She got five weeks of training in things like “introduction to classroom management” and “introduction to planning.” Then she was a teacher, in a huge, struggling high school.

“I would come in in the morning. I would close the door,” she says. “I would struggle through the day. I would cry three times a week after my third period which was my most challenging group of students. I would dust myself off. I would tell my fourth period class that I had terrible allergies and that’s why my eyes were so red.”

She says she got no help. The first time an administrator came to check on her it was January – and the administrator just needed to know if she had enough textbooks.

Green and Bankhead both wanted to become great teachers. But the system didn’t seem set up to help them do it.

A Long History

There are historical reasons for poor teacher preparation in the United States.

From the beginning, teaching was sold to the public as something that didn’t require much training. It was the 19th century, the United States was just putting universal public education into place, and people were worried about how much it would cost.

“We had to sell it to the taxpayers,” says Richard Ingersoll, a professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. “Costs had to be kept down. And so, you know, you didn’t want to have a lot of training, because you’d have to pay more for that.”

Lots of teacher preparation programs sprung up.

“They were very low entry standards, they were very inexpensive,” says Ingersoll. “The idea was to produce a whole lot of teachers as quickly and efficiently and cheaply as possible to staff this huge new thing, universal public education.”

And who was going to teach in all these new public schools? Women. This was a new idea. Teachers had mostly been men. The idea that women would staff these schools was part of the sell.

“The whole idea was that, we’re going to get women,” says Ingersoll. “They don’t have other job opportunities and we can pay them less.” Plus, women were good with kids, the thinking went, and teaching would be terrific practice for motherhood.

As soon as women became mothers, most of them quit or were fired. There was no incentive to invest in good preparation if women were only going to teach for a few years.

From the beginning, teaching was a high-turnover, low-status job. It was not seen as a career, a profession.

“We’re kind of stuck with that historical framework,” says Ingersoll.

Learning From Other Professions

Deborah Ball wants to undo this historical legacy.

The first step, she says, is to take a page from other professions. What other professions have done that teaching has not done, she says, is to identify the skills and knowledge that someone needs in order to enter the profession.

–Deborah Ball

“Not only many professions but many skilled trades are able to identify the core set of skills, techniques, knowledge that are at the core of doing that work responsibly to be good enough to be at an entry level,” she says.

To be a plumber, for example, you need to know how to vent a sanitary drainage system. To be a pilot, you need to know how to do a crosswind approach and landing. And you have to prove you can do these things to get licensed.

“This is true primarily at least across occupations and professions where people’s safety is at risk,” says Ball. “And I do think it’s of great concern that we don’t as a culture appear to think that children are at risk when we don’t execute that same kind of responsibility” when it comes to training teachers,

But she says there’s a lot of resistance to the idea of defining a core set of skills and knowledge that teachers should know before they start teaching. It goes back to the belief that the ability to teach is a personal trait, dependent on individual style and talent.

“Imagine any other skilled trade in this country, or profession, in which the practitioners of it always spoke in individual terms: if hairdressers said, ‘Oh, I have my own way of doing a layer cut’, or if surgeons said, ‘You know, I prefer to use plastic spoons when I do hernia operations,'” said Ball in a speech. “Or, you know, if my pilot gets on the PA system and says something like, ‘I hope you all won’t mind today, but I have a particular style of flying planes transcontinentally.'”

This gets a big laugh from her audience.

It does seem laughable. But for well over a century we’ve been sending teachers out into classrooms without the skills, techniques and knowledge that are necessary to be good teachers, she says. To change that, the teaching profession first needs to define what those skills, techniques and knowledge are.

High-leverage teaching practices

About 10 years ago, Deborah Ball and her colleagues at the University of Michigan decided to try to identify a core set of skills that people should have before they start teaching.

Tim Boerst, chair of the Elementary Teacher Education program, says the question they asked themselves was this:

“When a teacher goes out into the field, what are they routinely going to be needing to do? And how are those routines, those particular practices, really important in the learning of students? Because there are all kinds of things that teachers routinely do. Which are the ones that we’re going to be picking that we really think advance the learning of academic subject matter?”

They got a bunch of teachers and researchers together and came up with a list of the things they thought all beginning teachers should know how to do.

Their list had 84 things on it.

That was clearly too many. They needed a set of skills they could actually teach in their two-year program.

They whittled their list down to 19 skills and gave them a name: high-leverage teaching practices.

The list includes:

Leading a whole-class discussion. “In instructionally productive discussions, the teacher and a wide range of students contribute orally, listen actively, and respond to and learn from others’ contributions.”

Designing a sequence of lessons toward a specific learning goal. “Teachers design and sequence lessons with an eye toward providing opportunities for student inquiry and discovery and include opportunities for students to practice and master foundational concepts and skills before moving on to more advanced ones.”

Eliciting and interpreting individual students’ thinking. “To do this effectively, a teacher draws out a student’s thinking through carefully-chosen questions and tasks and considers and checks alternative interpretations of the student’s ideas and methods.”

Analyzing instruction for the purpose of improving it. “Learning to teach is an ongoing process that requires regular analysis of instruction and its effectiveness.”

Teaching the high-leverage practices

The specific skills you need for many occupations – such as knowing how to vent a sanitary drainage system to be a plumber or knowing how to do a crosswind approach and landing to be a pilot – these are skills most people wouldn’t learn unless they were training for that occupation.

Teaching is a bit different, because we were all students. We’ve spent years watching people teach. And we all do a certain amount of teaching in our everyday lives – giving people directions or showing someone how to do something.

Faculty at the University of Michigan want to know what students coming in to their teacher preparation program already know about teaching. That way, they can tailor their curriculum to focus on the things students don’t know. They can also focus on some things about teaching they want students to unlearn, habits or beliefs they picked up from their own years as children in school that are not productive ways to help kids learn.

To figure out what incoming students already know about teaching, Michigan has them do a role-playing exercise where they actually do some teaching.

The students are given a piece of paper with a math problem on it. The paper also includes an answer. This is an answer a student might actually have given to the problem. Here’s one of the problems the Michigan students are given.

The Michigan students are given a few minutes to look at the problem. Then they sit down with a graduate student or professor who plays the role of the kid who came up with the answer 83.

The Michigan student is told: “Your goal is to elicit and probe to find out what the ‘student’ did to produce the answer as well as the way in which the student understands the steps that were performed.”

A video camera is rolling to record what happens.

Often there’s a moment of awkward silence or giggles. This is kind of weird, a college student pretending to be a teacher and a professor pretending to be a little kid. But simulated assessments like this are actually common in other professions, particularly healthcare. Medical students routinely practice their clinical skills by interacting with people pretending to be patients.

“All right, so can you show me how you got this 623 from this problem here?” asks a Michigan student in one of the videos.

“Well that’s actually not my answer,” answers the person playing the kid, with a shrug in her voice that seems to signal, that’s all I’m going to tell you.

“That’s not your answer?” asks the Michigan student sounding a bit incredulous.

The point of this simulation is to see how well the Michigan student can elicit and interpret student thinking. That’s one of the high-leverage practices, and it’s hard to do.

First off, you, the teacher, have to figure out what the heck the kid did. The kid’s final answer is down there at the bottom of the paper: 83. That’s right. But what’s up with the 623?

Here’s how I was taught to do an addition problem with three two-digit numbers (I bet a lot of you were taught this way too): add up all the numbers in the ones column, carry to the tens column, add those up, done.

What did this kid do?

On another one of the videos, you can see one of the Michigan students have an “aha” moment. She’s been talking to the kid, and she suddenly seems to get what he did. He added the tens column first.

2 tens + 3 tens + 1 ten = 6 tens

Then, he added the ones column.

9 ones + 6 ones + 8 ones = 23 ones

So 623 represents 6 tens and 23 ones. The kid adds those up, and he gets 83. The right answer. It’s actually a pretty sophisticated method that shows a deeper understanding of the meaning of the numbers than the way I learned to do it. I would not have thought to do it this way.

The Michigan student who has had the “aha” about what the kid did says, “And that’s how you added 2 plus 3 plus 1 you get 6.”

“Uh-huh,” the professor playing the kid says, in a voice that sounds like he’d like to be anywhere but here explaining his math method to a teacher.

“And then you did the 9 plus 6 plus 8 to get 23?” asks the teacher, though it sounds more like a statement than a question.

“Uh-huh, that’s what I did,” says the kid, sounding bored.

“Ok, great,” says the teacher.

This interaction is an example of the kind of thing Michigan wants to teach its teachers not to do. Rather than eliciting the kid’s thinking, the “teacher” in this example was telling the kid what she thinks the kid was thinking, says Boerst. He calls it “filling in student thinking.”

“And that happens in classrooms all the time,” he says. “Teachers make assumptions about what kids are thinking. Kids don’t really know how to say otherwise or maybe aren’t inclined to say otherwise. Like, ‘Yeah, that’s what I was thinking cause I don’t really want to say what I was thinking.’

Boerst says this can lead teachers to think kids get things when they don’t.

What he and his colleagues have found by watching and coding these simulated assessments is that half of the students coming in to the elementary teacher prep program do this “filling in of student thinking.”

Undoing this habit one of the goals of the Michigan teacher prep program.

And the way you undo habits and help people form new ones? You get them to practice. Just reading or talking about the fact that you shouldn’t do this as a teacher isn’t enough, says Boerst. People have to practice doing it a different way. They have to practice, and practice, and practice.

Practice

Teacher preparation in the United States hasn’t been focused enough on practice, says Ball. That’s something that’s changed at Michigan.

Students used to spend a lot of time reading and talking about teaching.

“The assignments in the past were much more reflection, analysis,” she says. “In some sense we could have been misled by people getting good grades for writing well. And, although it may sound a little too extreme, I think we’re more interested now in whether they can do it well, not how well they can talk about it.”

So what does a teacher preparation program focused on practice look like?

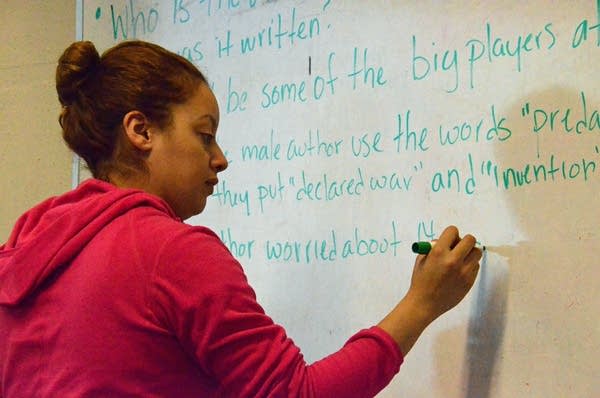

It looks like a place full of cameras and laptops. Students practice teaching, they record themselves while they’re practicing, then they watch the video and analyze it. Michigan even has a state of the art workspace called the Brandon Center where students and professors go to watch teaching video together. It’s got sleek modern furniture and a bunch of small conference rooms where you can plug in your laptop and watch yourself teach on a big, flat screen monitor.

I meet Anna Arias and Betsy Davis in the Brandon Center. Davis is a professor in the elementary teacher education program. Arias is a graduate student. They teach a class on how to teach science. One of the key features of that class is something called “peer teaching.”

Students in the class plan a lesson together. Then they take turns teaching it to each other. It’s all captured on video, of course. We watch one of them.

“So today, I want to ask you to read this question again,” says a student wearing Michigan sweatpants and a t-shirt.

She’s pretending to be a first-grade teacher. Her classmates and her instructor are sitting on the floor, pretending to be first-graders. The lesson is about why plants need stems.

“I think they help the plant eat,” says one of the first-graders.

“They help the plant eat?” says the teacher.

Stems don’t help plants eat. But “that idea, that plants eat food from the soil, is a typical alternative idea or misconception that children will have,” says Davis. The “first-grader” who said this was actually the instructor, and she said it to see how the teacher would deal with it.

The teacher in the video seems a bit unsure what to do. It’s hard to figure out how to respond when a kid says something like this. I know this from my own brief experience as a teacher.

Do you correct the mistake? That might shut down the discussion. Maybe it’s better to hear what all the kids are thinking first? But then you’re likely to have all kinds of wrong ideas out there. Kids might get confused. You might get confused. Suddenly the whole class is off in some other direction or tangent you didn’t plan for. When class is done, you’re not exactly sure what went wrong, but you’re glad it’s over.

“Many of us have had that experience of, ‘OK, phew, that’s over, I don’t have to do it again,'” says Davis.

But Michigan wants to teach its teachers to learn from their mistakes. It refers back to one of those high-leverage practices: Analyzing instruction for the purpose of improving it.

“By having the interns watch their own video of their teaching really carefully, they see things or they hear themselves saying things that don’t make sense or that are missed opportunities,” says Davis. “And that’s one of the things we ask them to highlight in their videos: what did you miss the chance to do that if you were doing this over you would do?”

A New Approach to Student Teaching

When Deborah Ball says she thinks teacher preparation needs to focus more on practice, some people look at her funny. Teacher preparation has always been focused on practice, they say. Student teaching!

Student teaching is a key part of many teacher preparation programs. (Though you may be surprised to know that data collected in the mid 2000s showed that more than 20 percent of first-year teachers had had no student teaching experience at all. Forty-two percent of science teachers did no student teaching.) Even though most teachers get some kind of student teaching experience, the quality of their experience varies a lot.

Remember Jasmine Bankhead, the student teacher who was left alone in the classroom on her very first day? I’ve heard a lot of stories like that over the years. Student teachers are either given too much responsibility, or they’re not given enough; they make copies or do recess duty. Or they just sit and watch the teacher teach. They might see really effective teaching. But they might not.

All of these things were happening when students at Michigan went out into the field for their student teaching experience. It was always a scramble to find classrooms to send them to. There was no consistency. Students “were actually starting to pick up some negative practices from the field, ” says Elizabeth Moje, an associate dean at the Michigan School of Education who helps oversee the student teaching program.

Moje wanted her students to see teachers who were really good at things like eliciting student thinking and leading class discussions. One day she and a colleague were talking and she was saying, if only we could just send the students to the three teachers we know are really good. And then a light bulb went off in her head. “Oh, we can!” she exclaimed.

Now, rather than sending the students out to dozens of schools all over the Detroit metropolitan area, Michigan rotates its students in groups to just a few different classrooms in a few different schools. It’s similar to the way medical students rotate through different specialties during their training. There’s a lot Michigan has borrowed from the medical field. In fact, all the students are now called interns.

My colleague Suzanne Pekow and I spent a day shadowing interns in the secondary teacher preparation program as they went on these rotations. Suzanne went with a group to a middle school just outside Detroit. They were also accompanied by a graduate student at Michigan, Rebecca Gadd, who advises them.

On Suzanne’s visit, the interns begin their day by checking in with the classroom teacher, Lauren Spoerl. Each intern will be working with a small group of kids on an assignment about the causes of the Civil War.

“OK, um, let’s go to the first question,” says intern Jesse Lu, seated with a group of kids. “Why was slavery so important to the South?”

“Um, it provided income,” says a student. “It was a way to trade goods and products so they can make money.”

–Rebecca Gadd

This is a fine answer, but Lu is trying to get the students to talk about a particular point in one of the readings they’d been assigned. He wants them to talk about how slavery gave some people social status, too.

But he’s struggling. He can’t quite figure out what questions to ask. There are a bunch of awkward silences as he waits, hopefully, for a student to pick up on the point.

Rebecca Gadd is observing. Finally, it gets kind of painful. So she stops the discussion and takes Lu aside for a quick timeout.

“OK, so what I would suspect is that the way that this is explained is a little bit abstract,” she says, referring to the reading assignment.

“OK,” says Lu.

“So you need to think, are you going to ask or are you going to explain?” She recommends that he stop asking the students questions because they clearly missed the point in the reading. It’s time to explain it to them. Just tell them what you want them to know.

Gadd is a former middle school teacher. She wishes her training had included this kind of guided practice. Teachers can go through their entire training – their entire careers even – without anyone taking them aside and offering in-the-moment feedback. She says Michigan got the idea for doing this from medical training.

“When aspiring doctors are practicing with patients, medical educators don’t wait until they’ve killed the patient to intervene and say, ‘You should have done this differently,'” she says. “Instead they intervene in the moment and say, ‘OK, we need to be doing this.'”

Becoming a Teacher

Michigan students in the secondary teacher education program spend two semesters in classrooms, observing and working with kids one-on-one or in groups. The idea is a gradual assumption of responsibility.

They don’t actually do what most people think of as student teaching until their third semester. That’s when they’re promoted from intern to resident, and they actually get to take charge and teach the class.

Grace Tesfae is in her semester-long residency, getting ready to graduate from Michigan in a few months. When I ask her how she feels about being a teacher next year, she says: “I feel good about it. I’m excited about it.” But, she adds, it’s “also scary. You’re by yourself, you’re planning everything. But, I feel like I’ll be ready when the time comes.”

Tesfae feels like she’ll be ready. But will she? It’s hard to know. Michigan doesn’t have much data yet.

And it’s not clear what kind of data would provide a meaningful measure of what Michigan is trying to do. They could look at test scores of students in their graduates’ classrooms. That would tell them something. But Michigan wants to know if its teachers can do things like elicit and interpret student thinking and lead class discussions. Test scores don’t tell you that.

Michigan does have its interns do one of those teaching assessments again, like the one where they tried to figure out what the kid was thinking with the math problem. By the end of their first year in the program, most interns are no longer filling in, rather than eliciting, a student’s thinking. The Michigan interns show progress on other elements of the 19 high-leverage teaching practices too.

But who’s to say those 19 practices are the right ones to be focusing on? I asked Deborah Ball that question.

“These are bets,” she says. “These aren’t necessarily the end, but they are the best bets we had. And we have to have a systematic way of revising those.”

In fact, Ball and her colleagues are revising the 19 high-leverage teaching practices now. The revisions will be published online soon. The changes are not dramatic, mostly language tweaks and shifts in emphasis. The skills teachers should know will probably always be evolving, as education changes, as students change, as research and practice lead to new ideas about effective teaching.

Bottom line though, from Ball’s point of view, is that the teaching profession needs to come to some kind of common understanding about the skills that are required to enter the profession. And just like plumbers and pilots, new teachers should have to demonstrate they have these skills.

She’s started an organization to try to develop new licensing assessments for people who want to be teachers and to work with teacher preparation programs across the country to develop common approaches to professional training. It’s a big job. The U.S. Department of Education projects that by 2020, the United States will need nearly 430,000 new teachers a year.

Ball’s ultimate goal is to make sure every first–year teacher in the United States is what she calls “a well-started beginner.” That’s what she and her colleagues are aiming for at Michigan.

“We’re really eyeing the first year, honestly,” she says. “Really the goal is that kids wouldn’t have first-year teachers who are completely underprepared, that it wouldn’t be true anymore that you could just end up with a teacher who, this is her year to have a wreck year.”

Ball feels particular urgency about this question because in the United States, it’s poor kids who are most likely to get first-year teachers. Ball says to improve education for all kids, and especially for poor kids, first-year teachers have to be much better prepared.

Teacher preparation is just one part of the story about how to improve teaching in America. Learn more about how teachers get better once they’re on the job.