The Wetterling abduction story kept getting bigger as the case — and Jacob's sweet smiling face — served as a conduit for public fear and grief. Capitalizing on a growing sense that pedophiles lurked in every shadow, the likes of Maury Povich and Geraldo Rivera joined the cause with sensational retellings of the crime and its consequences.

September 20, 2016

Jacob's parents, Patty and Jerry, were unable to protect themselves from the torrent of attention and information directed their way. They couldn't say no to a television appearance, refrain from answering the door or phone — the police set up a special phone in their home that had a recording device and rang constantly — or simply pull the shades and hide. They needed the public's help to find their son. They needed the public to care about Jacob, even the weirdos and broken people who insisted on sharing their theories and suspicions and advice. "You get more bees with honey," Patty Wetterling's sister told her.

With every news story and television appearance came more leads from all over the country, first by the dozens, then the hundreds and the thousands. Sports figures publicized the case. Thousands of fliers were distributed. There were so many leads that law enforcement set up a 24-hour call center just to keep up.

Meanwhile, investigators entertained ever greater longshots. They issued police sketches of strange and suspicious men, some vague enough to have been drawings of anybody. They enlisted the public's help in finding red cars and white cars and tan vans, cars seen moving suspiciously slowly or suspiciously quickly. They even conducted a search in Iowa based on a lead from a psychic.

Meanwhile, Danny Heinrich — a suspect in a previous sexual assault that bore a striking resemblance to this one — had killed and buried Jacob just outside his hometown of Paynesville, 30 miles away.

The misunderstood police sketch

Two weeks after Jacob Wetterling was abducted in St. Joseph in October 1989, an older man walked into the very Tom Thumb store where the 11-year-old had rented a video the night he went missing. The man acted strangely, said a clerk, as he purchased chicken noodle soup and saltine crackers. He talked about Jacob and said with a chuckle, "I don't think they're ever going to find that boy." The clerk didn't get the man's license plate number, but she worked with police to create a composite sketch of his face.

That sketch became one of a number created and publicly disseminated during the Wetterling investigation. There were drawings of men suspected of related abductions or attempted abductions, of skulking men who had been seen in cars and of one man described as possessing a "piercing stare." The police even released a Frankenstein-like combination sketch comprising features from three previous drawings. In 2015, one of these sketches, which bore a striking resemblance to Danny Heinrich, who subsequently admitted abducting and killing Jacob, was used to support a search warrant for Heinrich's Annandale house.

But the creation of composite drawings is a misunderstood and sometimes overvalued aspect of police work, representing the tangible result of a highly abstract process.

How hard is it to get a police sketch right? Very, we found out

Calls to the Wetterling house

Investigators set up a special phone line at the Wetterling home to receive potential tips, and calls came in by the thousands. Some callers were self-proclaimed psychics; some said they saw Jacob in dreams; some reported possible sightings of a boy who looked like Jacob. Here are several excerpts.

The truth about lie detector tests

The police subjected Jacob Wetterling's parents, Jerry and Patty, to polygraph testing after their son was abducted in 1989. "It's horrible," recalled Patty, who was tested by the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. "They wire you up. They ask you a bunch of questions to get a base line. 'State your name. State your age.' And then they will ask you a question like, some ridiculous thing, 'Have you ever lied?' Which is, you know, everybody has."

Polygraphs — which measure changes in heart rate and blood pressure, breathing patterns, and skin conductivity via sweat in an effort to determine whether someone is lying — were used extensively in the Wetterling investigation, on suspects and potential witnesses.

Despite the continued employment of polygraph testing by law enforcement, the tests don't reliably or consistently work. They are considered by many in the scientific and legal communities as only marginally more accurate than coin flips. Consequently, most courts do not admit polygraph evidence.

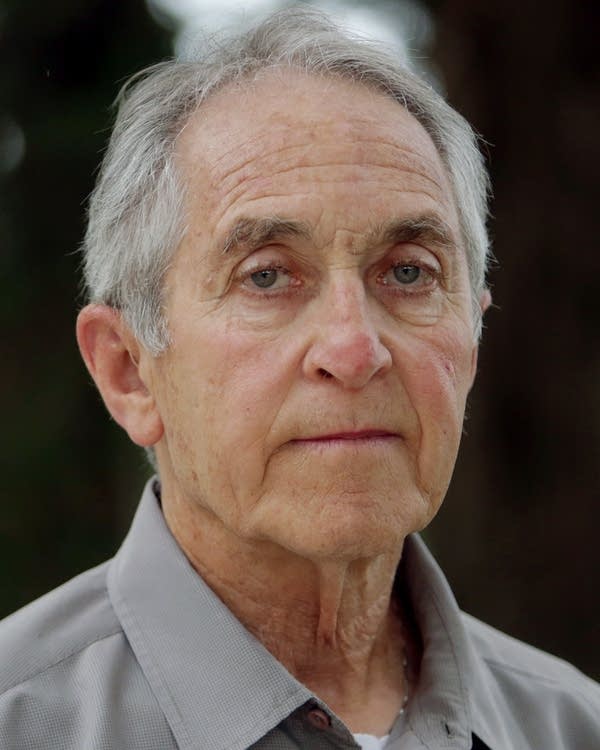

Profile

FBI AGENT, RETIRED

FBI AGENT, RETIREDAl Garber

Al Garber was the FBI agent who led the early investigation into the abduction of Jacob Wetterling. A New York native, Garber is disciplined, direct and fiercely loyal. Asked about early suspects in the case, Garber — whose 2010 memoir is called "Striving to Be the Best" — seemed to perceive a criticism. "Nothing slipped through the cracks," he said. "What was done was what we could do."

Does hypnosis help solve crimes?

Dan Rassier, who lives on the farm at the end of the driveway where Jacob Wetterling was abducted in 1989, remembers being driven by detectives from his home near St. Joseph, Minn., to the Twin Cities to be hypnotized.

During what he described as a "high state of concentration," Rassier remembered seeing a person in the passenger seat of the car, a woman or child. Today, he doesn't know if that memory is real or concocted while under hypnosis. "I'm not sure whether somebody was looking out the window," he said. "In my memory, I see someone looking out the window, but I don't know if I really saw that."

That's one problem with the use of hypnosis in criminal investigations, known as forensic hypnosis. Especially if done poorly, the process — basically a means of trying to induce a more focused state of mind — can plant memories or skew existing memories.

On the night of the abduction, the police didn't search the property of neighbor Dan Rassier very thoroughly. Years later, it was a decision he came to regret a great deal. → Episode 5: Person of Interest

Natalie Jablonski

Chris Worthington

Catherine Winter

Hans Buetow

Dave Peters

Andy Kruse

Jeff Thompson

Gary Meister

Curtis Gilbert

Jennifer Vogel

Will Craft

Feedback and support

We're interested in hearing about the impact of APM Reports programs. Has one of our documentaries or investigations changed how you think about an issue? Has it led you to do something, like start a conversation or try to do something new in your community? Share your impact story.

Your financial support helps keep APM Reports going strong. Consider making a tax-deductible donation today.