After re-examining the case, we'd found no direct evidence linking Curtis Flowers to the murders at Tardy Furniture. But we had one lingering question: How did Flowers become the main suspect? Why would investigators focus so much on Flowers based on so little evidence? In short, why Curtis? We decided to find out.

June 19, 2018

District Attorney Doug Evans offered a simple reason for why Curtis Flowers wanted to commit murder at Tardy Furniture on the morning of July 16, 1996: revenge. In Evans' telling, Flowers had been fired from the store after dropping golf cart batteries he was transporting. So, according to prosecutors, he was going to get even by robbing the store and killing the employees.

But the prosecution's narrative doesn't entirely fit the available facts.

For one, Flowers wasn't fired. Flowers said that he simply stopped showing up for work. This was confirmed by two of the victims' relatives, Frank Ballard, Bertha Tardy's son-in-law, and Benny Rigby, whose wife, Carmen, was the bookkeeper at Tardy Furniture. "He just didn't come back, from the way I understand it," Benny Rigby said. "He decided not to show up."

There's also no reliable evidence that Flowers was angry with owner Bertha Tardy. At his first trial, the only time he's taken the stand, Flowers said he only worked at the store for three days total and then didn't return after the July 4th holiday. He testified that he skipped work for three days while he was seeking another job, at a company that makes brake pads for cars. When that job fell through, he called Bertha Tardy on Tuesday, July 9, to ask if he could come back to work. This was a week before the murders. She told him that she'd already hired replacements, according to Flowers' testimony. They parted on good terms. That, he said, was the end of it. This wasn't the first time Flowers had lost a job for simply not showing up.

Flowers also testified that he'd harbored no angry feelings toward Tardy. In fact, he said, he'd appreciated that, on his last day of work, she'd given Flowers a $30 advance on his paycheck so he'd have extra money for the July 4th holiday.

Evans theorized in court that Flowers was angry that Tardy docked money from his paycheck. Tardy was withholding a check for $82.58 while she tried to get the supplier to cover the cost of the broken golf cart batteries. Factoring in the $30 advance he'd received, Flowers was missing $52.58. So one key question about Flowers' supposed motive is this: What kind of person flies into a murderous, vengeful rage — and remains in that rage for a week — over $52.58? And is Curtis Flowers — a man with no criminal record and no history of violence — that kind of person?

Investigator John Johnson first interviewed Curtis Flowers on the afternoon of July 16, 1996, roughly four hours after the murders. Flowers talked to investigators two more times that week, on July 18 and July 23.

In his statements, Flowers explained that he'd spent the morning babysitting his girlfriend's kids on the west side of Winona. He recounted the story of the dropped golf cart batteries and the circumstances of his departure from Tardy Furniture. He told investigators that he'd felt no animosity toward Bertha Tardy.

You can read Flowers' statements to law enforcement below. There's a full transcript of his second interview. For the other two, there are only investigators' typed notes and observations.

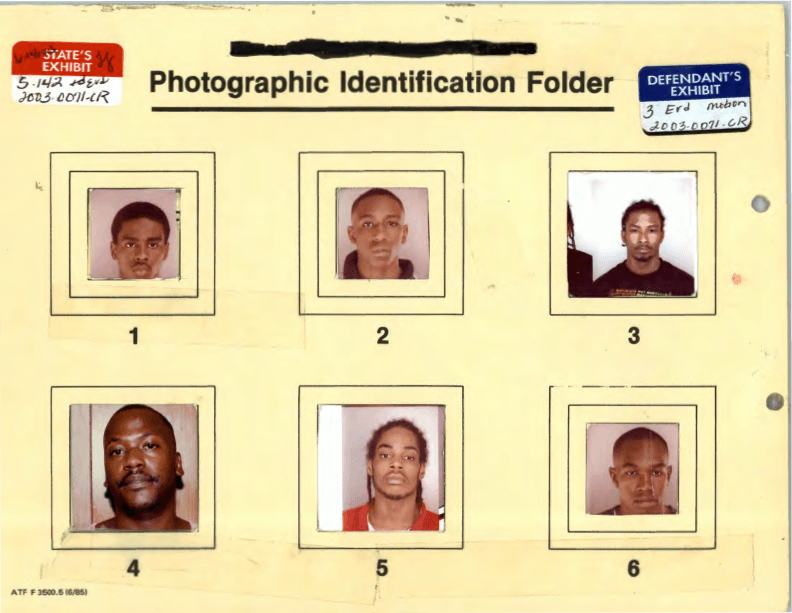

A photo lineup is a classic investigative tool. For decades, police have presented crime witnesses with arrays of images known as "six-packs" and asked them to pick out the perpetrator they saw.

But it wasn't until 1999, as a growing body of social science on the nature of eyewitness memory was emerging, that the U.S. Department of Justice first issued guidelines about how photo lineups should be conducted. Before that, law enforcement officers used whichever technique seemed best to them, sometimes with tragic consequences.

Of the 358 people exonerated by DNA in the United States since 1989, nearly three-quarters were sent to prison at least in part by mistaken eyewitness identification. It is the leading cause of wrongful convictions, according to the Innocence Project.

In the Curtis Flowers case, two witnesses were shown photo lineups more than a month after the murders. One was Porky Collins, who said he saw two African-American men across the street from Tardy Furniture not long before the murders. The other was Catherine Snow, who said that, on the morning of the murders, she saw a man standing next to Doyle Simpson's car outside the Angelica garment factory, where she worked. This seemed significant because prosecutors believed that the murder weapon was stolen from Simpson's car.

Both Collins and Snow eventually picked Flowers out of photo lineups, with varying levels of certainty. But how reliable are their identifications?

We talked to two psychologists who are experts on eyewitness memory — Iowa State University's Dr. Gary Wells and Dr. John Wixted from the University of California, San Diego — about what makes for strong identifications. Then we graded the two photos lineups in the Flowers case against the five criteria the experts provided.

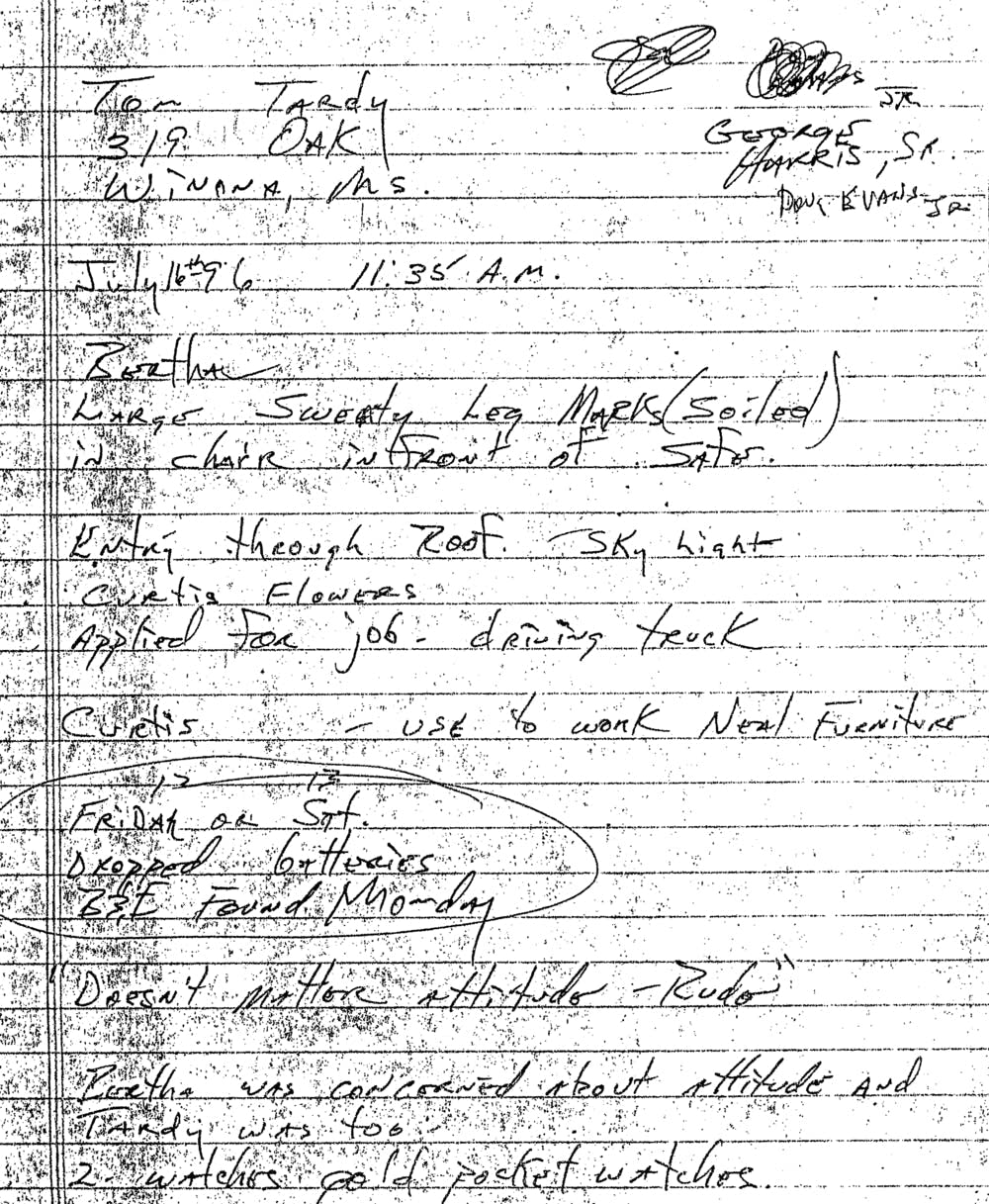

The investigative file in the Tardy Furniture case consists mainly of short, handwritten notes made by investigator John Johnson. In most instances, the notes are so brief, it seems unlikely they describe all that was discussed in interviews with Johnson. And they may not be completely accurate. Seventeen people told us that Johnson's notes of his interviews with them contained statements that either weren't entirely true or that they'd never made. You'll find below images of some of Johnson's notes in the case.

Tom Tardy

Johnson spoke to Tardy at 11:35 a.m. on July 16, 1996, just two hours after the murders. Tardy is the first person to cast suspicion on Flowers. He described Flowers as having a bad attitude. He also said someone had broken into the store the week before and left sweat stains on a chair. The note below is all that's in the investigative file about Johnson's initial interview with the husband of murder victim Bertha Tardy.

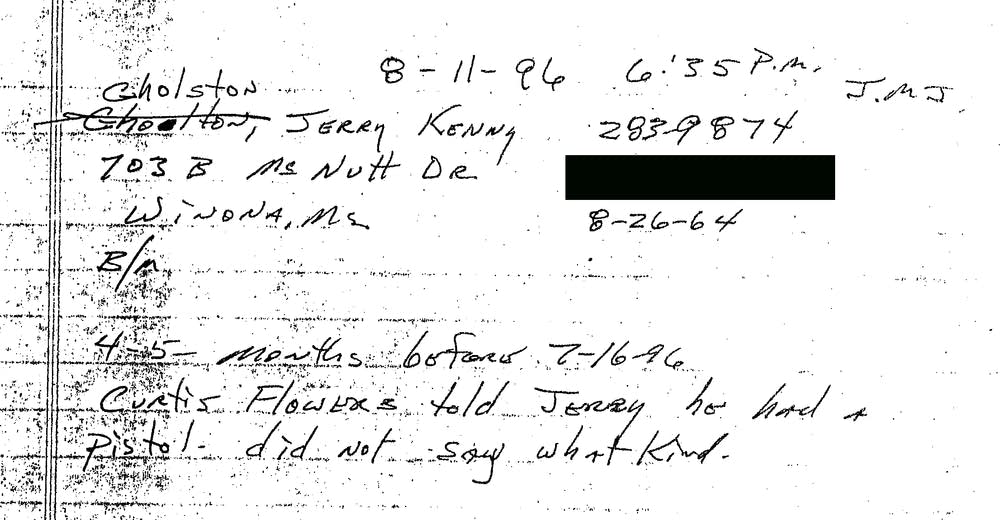

Jerry Ghoston

According to Johnson's notes, one of Flowers' neighbors, a man named Jerry Ghoston, said Flowers owned a gun. In an interview with "In the Dark," Ghoston denied that Flowers ever said anything about having a pistol. Johnson also misspelled Ghoston's last name.

Antonio Earl Campbell

A number of notes involve whether Flowers wore Fila sneakers. In an interview, Campbell denied that he told Johnson this.

Lawanda Glover

She also denied telling Johnson that she saw Flowers wearing Filas. "No I did not say that," she told us. "I put that on my children. I did not say that."

John Johnson, a key investigator in the Curtis Flowers case, refused numerous interview requests from "In the Dark." In fact, the only time we ever saw Johnson during a year of reporting in Mississippi was when he was invited on stage to sing with Benny Rigby's band at The Pizza Inn in Winona. After his performance, he slipped out a back exit. We never got to ask him why he investigated the Flowers case the way he did.

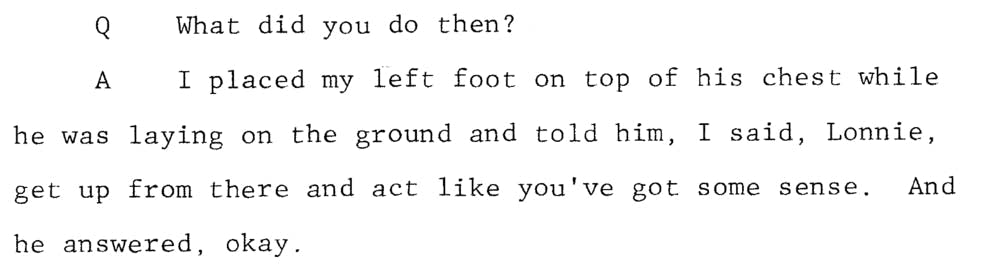

The most extensive record of Johnson talking about his work comes from a sworn deposition he gave in 1978 after he was sued in federal court. The plaintiff in the case was a white Winona man named Lonnie Blaylock, who alleged that Johnson had knocked him to the ground late one night outside a coffee shop, then kicked him in the head and stepped on his throat. Johnson then dragged Blaylock toward his police cruiser, the suit said, twisted his arm, pulled his hair and punched him again. The City of Winona settled the suit for $1,000.

In his deposition, Johnson said he encountered a drunk Blaylock in the cafe and asked him to step outside. Once outside, Johnson tried to grab Blaylock's arm — he said he was planning to arrest Blaylock.

"Just reached to get him," Blaylock's lawyer said. "Is that correct police procedure?"

"I don't know," Johnson replied, "but in a small town in a community where you know everybody, I'm sure the procedures are not what they would be in a larger town."

Blaylock drew his arm away, making Johnson think he was going to hit him. So Johnson punched him, according to the deposition.

"He bumped the glass on the restaurant and fell to the ground," Johnson said in the deposition.

Johnson said he punched Blaylock again, in the mouth, as Johnson was trying to put him in a police cruiser.

"He never did hit you," Blaylock's lawyer said.

"He never did," Johnson confirmed.

From the deposition, we also learn a bit more about Johnson's background. He was 28 at the time and had been a cop on and off for five years.

Johnson said he had graduated from Winona High School in 1968. After that, he'd spent two semesters in night school at a junior college and five weeks in the state law enforcement academy. Then he worked at his father's service station for several years before he joined the Winona Police Department.

The Winona Times, announcing Johnson's hire in September 1972, wrote, "Mayor Fred Watts, in outlining the young man's qualifications, noted that he holds a first degree black belt in karate."

Johnson lasted less than a year at the department. "I terminated myself," he said in the deposition. "I had a political disagreement with the mayor." Johnson went back to work for his father.

A year or so later, he got a job at the nearby Grenada Police Department, where Doug Evans was working. Johnson left the Grenada force after a short time and returned to Winona.

Blaylock's lawyer asked Johnson about his time in Grenada.

A month after his October 1976 run-in with Lonnie Blaylock, Johnson quit the Winona police for a second time. Asked by Blaylock's attorney why he left the force, Johnson said, "Well, it seemed to me that law enforcement was just too much of a hassle."

Johnson would return to the Winona Police Department for a third time, in 1979, and rise through the ranks to become chief of police. Twelve years later, after Doug Evans was elected district attorney, John Johnson would be one of his first hires.

Natalie Jablonski

Rehman Tungekar

Parker Yesko

Will Craft

Dave Mann

Andy Kruse

Catherine Winter

Chris Worthington

Gary Meister

Johnny Vince Evans

Corey Schreppel