'All of us failed'

Law enforcement comes clean on botched Wetterling investigation

Two years after the first season of In The Dark revealed numerous mistakes by law enforcement investigating Wetterling's disappearance, the Stearns County sheriff provided harsh detail of his predecessors' failures and made public thousands of documents from the investigative file.

September 20, 2018 | by Parker Yesko

For nearly 29 years, no one in law enforcement had explained why Minnesota's most famous crime — the October 1989 abduction and murder of 11-year-old Jacob Wetterling — had remained unsolved for so long. Nor had anyone taken responsibility for it.

That all changed on Thursday morning in a remarkable press conference by Stearns County Sheriff Don Gudmundson.

The occasion, which drew 80 people and 20 news cameras to a packed basement room in the Stearns County Sheriff's Office, was the release of the state's 41,787-page investigative file. Gudmundson, who assumed office in May 2017, could have simply released the documents, complying with a court ruling that they be made public, and left it at that. But instead, he provided the first public accounting of how and why law enforcement botched the investigation.

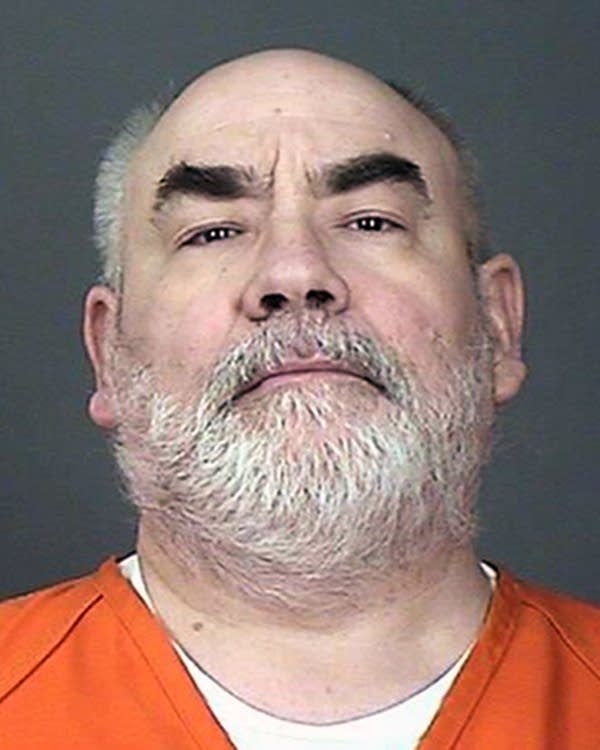

For nearly 90 minutes, he explained in painful detail why law enforcement had failed to catch Jacob's killer, a local man named Danny Heinrich, for 27 years. His assessment was scathing and candid.

"I will accept the responsibility speaking for all of law enforcement in this case," Gudmundson said. "All of us failed."

Wetterling's fate had been unknown until Heinrich, who'd been jailed for possession of child pornography, confessed in 2016 to murdering the boy and led investigators to his remains outside Paynesville, Minnesota.

A number of law enforcement's critical missteps were reported in Season 1 of APM Reports' "In the Dark" podcast, released just after Heinrich's confession. Investigators failed to thoroughly canvass Jacob Wetterling's neighborhood in the days after his disappearance, they didn't connect the Wetterling case to other similar crimes in the area in which Heinrich was already a suspect, and they mistakenly and very publicly pursued a man who had nothing to do with the crime.

Gudmundson stood at the front of the room in his blue suit, gold badge hanging from his left breast pocket. He began speaking at 10:06 a.m., and it took less than a minute for him to acknowledge what many had worked hard to find out: that the investigation into Wetterling's kidnapping and subsequent murder "went off the rails."

It was a stunning admission from the head of an agency that, until then, had been reluctant to rehash failures of the past. Gudmundson's predecessor, Sheriff John Sanner, said in 2016, "Over the years I've been asked to look back and comment on things that might have been done differently. My response has always been the same. Our energy needs to stay focused on what we can control and not waste it on things we have no control over."

But as Gudmundson made clear on Thursday, the Stearns County Sheriff's Office lost control of the investigation and should have caught Heinrich much earlier.

He noted multiple pieces of evidence that linked Heinrich to a string of abductions and assaults in the county, including his attack on Wetterling. "When Heinrich comes, because the case is so big, they're so overwhelmed, it was like a whisper in the crowd. But you know what it should have been? A persistent whisper," he said.

He described the investigation as slow and chaotic, marred by inter-agency distrust and redundancies. He blamed the FBI for pursuing far-fetched theories and for relegating more experienced state investigators to checking out dead-end leads.

"There was a lot of manpower; most of it was squandered," Gudmundson said.

He detailed a number of leads that were overlooked and that would have connected the Wetterling case to similar crimes in the area, including the kidnapping of 12-year-old Jared Scheierl in early 1989 and a series of attacks on young boys in nearby Paynesville.

He said authorities received a tip less than 48 hours after Wetterling was abducted, from a boy who'd been attacked by a man in Paynesville who used the same "quick, military, and proficient" style as Jacob's abductor. Yet it took investigators nearly three months to follow up on this lead.

When investigators finally did begin to investigate Heinrich, Gudmundson said, they ignored key evidence and made several critical errors that allowed him to slip away.

On Jan. 12, 1990, Heinrich failed a polygraph test. The same day, he was put under surveillance and Sheriff's Detective Steve Mund photographed the Sears Superguard Radial tires on Heinrich's car. They matched plaster casts of tire tracks that Mund himself had made at the site of Wetterling's abduction. Though the plaster casts were used to rule out a number of other suspects, they weren't used to rule Danny Heinrich in. The surveillance effort was abandoned after three days.

In late January, Heinrich consented to being in a live lineup. Scheierl, who said he was having difficulty remembering what his abductor looked like, didn't pick out Heinrich. Gudmundson said the lineup should have been shown to the seven victims from Paynesville and the two boys who were with Jacob when he was abducted. He also said investigators should have had Heinrich read lines he allegedly said during his crimes, because victims had described a man with a low voice. None of that was done.

On Feb. 9, Heinrich was finally arrested by Stearns County detectives and brought to the Sheriffs' Office to be interrogated. Gudmundson said that Heinrich was drunk at the time — he'd been picked up at night at a bar — and that the FBI agents who interrogated him were inexperienced. Gudmundson said that arresting a suspect who was drunk was the result of poor planning. Heinrich strongly denied any connection to the Wetterling abduction and was released. According to Gudmundson, the FBI profilers told a Stearns County detective that they didn't think Heinrich was guilty.

"We regard the interrogation as perhaps the most fatal flaw in the Wetterling investigation," Gudmundson said.

By June 1990, Heinrich had been all but forgotten. He wasn't even questioned in March 1991 when another known sex offender in the area, Duane Hart, implicated Heinrich, who was a friend of his. Hart told investigators that Heinrich had a gun and a black ninja-style suit that resembled descriptions of the perpetrator's clothing and that the same month as Wetterling's abduction, Heinrich had asked him how to dispose of a body.

Gudmundson said there was no further mention of Heinrich in the investigative file for 20 years. During that time, Sanner aggressively pursued another man, Dan Rassier, who had nothing to do with the crime.

Months after the first season of "In the Dark" was released, then-Sheriff Sanner abruptly resigned and recommended that his chief deputy replace him. Reporting from "In the Dark" was raised in a county board meeting about the selection process for filling Sanner's seat. Ultimately, the board chose Gudmundson, who was known as a reformer with experience managing other troubled departments.

The release of the investigative file had long been expected but was delayed due to litigation. The Wetterling family had sued to keep certain personal details private. The Department of Justice also successfully filed a complaint to reclaim the FBI's documents, arguing that they'd only been on loan to the county. Gudmundson said that 12,545 pages had been pulled from the file and returned to the FBI.

As Gudmundson left the podium, Al Garber, who had been the FBI task force commander on the case, approached the podium unexpectedly and began criticizing Gudmundson's characterization of the investigation as having gone "off the rails."

Gudmundson asked Garber to address the media outside. Garber said that the sheriff couldn't understand the task force's day-to-day activities and said that agents had done all they could to find the killer.

Asked earlier whether he was using hindsight to criticize the investigation, Gudmundson had said, "I have laid out, I think, in a measured, clear, concise and precise manner the way I saw it based on the reading of the file. If [the FBI] somehow would challenge my assessment, release their files. They've got files. Release them."

No one who investigated the case remains in the sheriff's department, and no one will face discipline. You can't punish an investigator for a poor investigation, Gudmundson said. But for at least one day, a law enforcement official finally offered an explanation and some accountability for what happened.

"We can't change what's happened," he said at one point, choking up, "but we can learn from it."