A system meant to give college students a better shot at succeeding is actually getting in the way of many, costing them time and money and taking a particular toll on students of color.

August 18, 2016

Latasha Gandy thought she was the ideal high school student.

Attending Arlington Senior High School in St. Paul, Minn., she kept her head in her books and did her homework. "I was that student everybody wanted to multiply," she said.

Her mother was elated with Arlington, a brand new school with the latest technology, web training, access to Apple computers and — best of all — the promise that it would prepare every student for college. Gandy's parents hadn't gone to college.

Gandy was in the honors program and graduated with a GPA of 4.2 out of 5.

But when she went to enroll at her local community college, a counselor said she had to take a placement test. When the results came back, Gandy was told she needed remedial classes.

"My first question was, 'What are those?'" she recalled, the surprise still evident in her voice. "And they told me they were basically material to catch me up to be ready to be in college. And I remember asking, 'How is that possible that I'm not ready for college when I graduated with a 4.2 GPA?'"

It was a huge blow. Financially, because remedial classes, also known as developmental classes, cost money but don't count as credit toward a degree. And emotionally, because she started to wonder if she really belonged in college at all.

"I went into this state of, 'Black people don't go to college,'" Gandy said. "That's something that I heard very often in my childhood. Not in my home, but I heard it in my neighborhood. I heard it from older adults that were around me."Gandy had run into the nation's increasingly cumbersome problem with developmental education, a system that is intended to give students a better shot at succeeding in college but which, according to mounting evidence, is costing students time and money and actually preventing some of them from getting degrees.

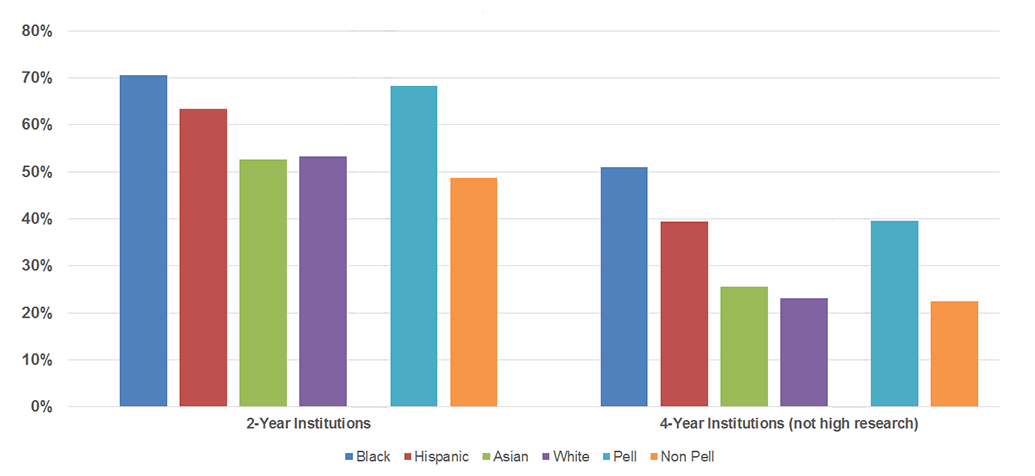

More than four in 10 college students end up in developmental math and English classes at an annual cost of approximately $7 billion, and many of them have a worse chance of eventually graduating than if they went straight into college-level classes. Students of all races and income levels end up in developmental classes, but students of color like Gandy are significantly more likely than white students to end up in remediation. Low-income students also are more likely to be assigned to developmental classes.

Remedial education enrollment by race, income

Many people point first to inadequacies in the nation's K-12 education system for letting students graduate without being ready for college. But identifying what skills students actually need in college and how best to learn those skills can complicate the question.

Part of the problem is the standardized tests used to place students in developmental education. Studies show up to a third of students assigned to developmental classes based on placement test scores could have gone straight to a college class and earned a grade of B or better.

It's a problem I experienced firsthand when I tried taking a placement test this winter, more than 20 years after graduating from college.

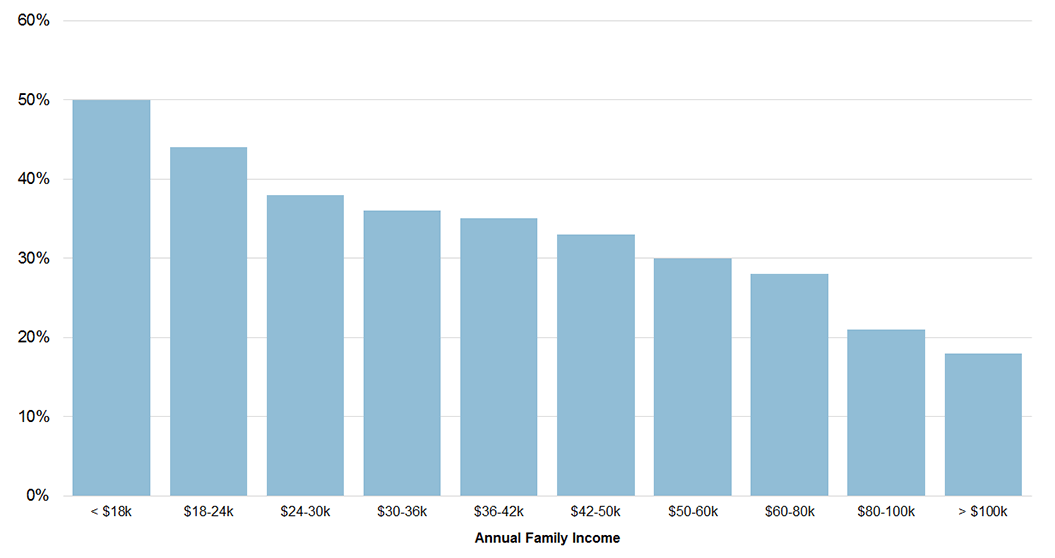

Percentage of students in remedial classes by family income

Old problem with modern trappings

The problem of students not being ready for college is as old as American higher education. In the 1630s, Harvard had to provide Greek and Latin tutors for the unprepared.

But the modern form of remedial education took root in the late 1960s, when black and Puerto Rican protestors demanded changes to admissions policies at the City University of New York (CUNY). They wanted more low-income students of color to gain access to higher education.

Starting in 1970, trustees agreed to admit anyone with a high school credential and to provide remedial help for those needing it.

CUNY trustees believed that without it many students would fail.

Remedial education seemed to be a win-win for students, helping those who were behind learn the skills they needed to be successful in college classes but also keeping them out of college classes so the instructional level wouldn't fall.

But Elsa Nùñez began to wonder if remedial education was really helping when, in 1986, she became a dean at one of the colleges in the CUNY system, the College of Staten Island. Nùñez was stunned to learn that only 7 percent of students who started in remedial classes were making it to graduation. They were in a special program for low-income students who had not done well in high school.

The faculty member who ran the program insisted that being in college was a good thing for the students even if they didn't graduate, said Nùñez. "They're having a good experience," she told her. "They're maturing, they're meeting other people, their self-esteem has built up. They've bettered themselves in many good ways."

Nùñez didn't think that was enough and raised the issue with her superiors. But she soon realized there was little appetite for questioning the effectiveness of remedial education. White administrators were afraid of being called racist for pointing out the high failure rate in a program that served mostly students of color.

"People thought 'this is just the way it is,'" said Nùñez. "'We're lucky we've gotten to a situation where (students of color) are admitted.'"

But Nùñez, who was born and raised in Puerto Rico, thought the college should be doing more to help students actually get degrees. What's the value of access, she thought, if there's virtually no chance of success?

It wasn't until the 1990s that researchers and federal agencies began generating much study looking beyond college access to college success.

When they did, the news wasn't good. Only 36 percent of people who begin at community colleges, where most students start in developmental classes, end up getting degrees. And if you have to take a developmental class, your chances of graduating are just one in four, an indication those classes are not helping students graduate.

And developmental education may actually be hurting some students. One study found that students who ignored a developmental placement and enrolled directly in a college-level course were substantially more likely to pass the college class than students who went to remediation first.

Starting to tackle the problem

One place this research ignited a conversation was Connecticut.

Elected to the state senate in 2010 and assigned to chair the higher education committee, Beth Bye went on a listening tour to meet students and faculty at the state's public colleges and universities. Remedial education kept coming up.

"The students were saying that some of them spent two years in remedial education," she said. Students could be assigned to as many as three levels of math remediation and three levels of English.

They were taking out loans, burning through their financial aid, and most were never making it to entry-level classes in the subjects they were interested in, such as psychology or criminal justice or health management.

Percentage of students who start in remedial classes and go on to pass the associated college-level courses

"I was really shocked when I heard that students couldn't get in to entry-level classes," Bye said.

Professors insisted students couldn't succeed in college-level classes unless they finished their remedial coursework first. But that argument hit a nerve with Bye.

She had been impressed by the experience of her wife, Tracey Wilson, a long-time public school teacher whose high school decided to let any student enroll in academically challenging Advanced Placement classes. Previously, students needed certain grades or test scores to get into AP.

But the new idea was to have no litmus test, no bar.

It was counterintuitive. Wilson said students with low skills, students who could barely write a paragraph, used to be put in classes that drilled down on things like grammar and spelling. But putting students in more advanced classes helped them learn those skills better, she said.

"It was totally based on faith that this was going to happen," Wilson said. "But it did."

Bye thought that could apply to remedial education in colleges.

So in 2012 she introduced a bill to prohibit public colleges from forcing a student to enroll in a remedial course before starting entry-level classes.

"If your focus is on the role higher education plays in trying to make this a country of equal opportunity then the most important thing we do is developmental education. And it's really crucial that we fix it." Peter Adams

The backlash was immediate.

"There was a huge, 'Please don't do this,' from people I respected a great deal," she said. "Really successful community college presidents who said, 'You can't just do that.'"

One of the people who said it wouldn't work? Elsa Nùñez, the former CUNY dean.

Nùñez, now president of Eastern Connecticut State University, said her initial reaction to Bye's bill was mixed. On one hand, she was grateful that a state senator was asking questions about the effectiveness of developmental education.

On the other hand, Nùñez said, many students need developmental classes to make up for what they didn't get in high school. The only way community colleges could allow all students into college-level classes would be to do away with open admissions, she said. In other words, shut the door on people who didn't get good preparation in high school and give many low-income students of color no chance of getting a college degree.

So Nùñez and Bye worked with higher education leaders across the state to come up with a compromise. Under a new state law, public colleges and universities can offer only one semester of remedial classes, and students can't be assigned to remediation based on only one test score.

In addition, the state established a new system of classes for students who would have previously gone into the lowest level remedial classes, and those classes are free, an acknowledgement that the K-12 education system let those students down.

Free classes with a surprise

I met Hector Ponce in one of these classes.

Ponce was born in Mexico but came to the United States when he was 4 and went to American public schools. He graduated from high school in 2002 and works at Starbucks.

"I want to do better," he said. Ponce is the first person in his family to give college a shot. He's hoping to get a bachelor's degree.

"And even if I don't get there," Ponce said, "I don't want to give up on an opportunity that's been given me." He told me he wouldn't have been in the developmental classes if they weren't free.

In a group lesson, instructor Emily DeToro focused on the basics of grammar and word usage. DeToro was a lively instructor, moving quickly through material that was clearly challenging for many of the students.

"I'm going to start with verbs, OK?" DeToro said to the class. The students' homework had been to identify parts of speech in sample sentences. DeToro read one of the sentences out loud: "During one part of his life, Picasso preferred the color blue."

She called on a student to identify the verb.

"During," the student said, his voice lilting upwards to indicate he was not at all certain.

"Umm, not so much 'during,'" said DeToro. "Where's the action taking place?"

Another student offered, "Is it 'preferred?'"

"Nicely done," said DeToro.

For Ponce, the class was a wake-up call. "I feel like I should be excellent on all this and I'm just realizing, 'Oh, my God,' I don't exactly know all this stuff," he said.The purpose of the free developmental classes in Connecticut is to improve students' scores on the Accuplacer test because that's what will get them into a college class.

The Accuplacer is a standardized math and English test used by most community colleges to determine who is ready for college-level classes. (Try some sample questions.) Even though, under the Connecticut law, the test is not supposed to be the sole criterion for deciding who goes into developmental classes, most incoming community college students still take the test, and most students are still placed based on the results.

That doesn't mean what students are learning in those free classes will actually prepare them for college-level work. Identifying verbs is probably not something any of them will ever be asked to do in college.

But if you can't identify the verb in a sentence, should you be allowed in a college class?

Absolutely not, said several professors I talked to in Connecticut.

"There are certain basic skills you have to have before you can do higher order learning," said Kevin Buterbaugh, professor of political science at Southern Connecticut State University. "If you come into my class where we're reading abstract articles on war or international relations and you can't read or you can't write about those things, I can't get you to learn about the material. You have to have basic, functioning academic skills in order to participate constructively in the class."

At the heart of the debate about developmental education is the question of what works best to catch people up on academic skills if they didn't learn them the first time around in school.

Research shows basic skills instruction, such as having students identify the verbs in sample sentences, is not an effective approach. Yet this kind of instruction, often referred to as "skill and drill," is how most developmental classes are taught. Researchers say this may be one reason developmental education is ineffective for many students.

And indeed, by the end of the semester, when I caught up with him again, things were not going well for Ponce. He and his classmates had just taken the Accuplacer test again, and Ponce's scores — in both math and English — had gone down. He was surprised.

"I can't say I've learned everything," he said. But he thought he was making progress. To have his test scores go down was a big blow.

Ponce told me he was thinking of giving up on college. But then he said something that surprised me. All the time he was taking the free developmental class, he was also taking an English class at nearby Middlesex Community College.

"I'm actually in English 101," Ponce said.

English 101 is a college-level class.

It wasn't exactly clear how he had been able to do that, but he said he started taking the free remedial English class because he thought it was required when he took the remedial math class.

And the way he ended up in college level English? He went to enroll at the community college and was placed in an upper-level remedial class because under the new law, the college can only offer one semester of remediation.

He got a C in that class, good enough to get him into English 101.

But his scores on the Accuplacer test had him worried he might not really be ready for college. "I feel frozen," he said. "I feel like I can't move forward."

Ponce might not yet have the skills he needs to succeed in higher level college courses.

But research suggests that how he or anyone else does on a placement test is not a very accurate predictor of how they will do in college. Two recent studies found that up to a third of students assigned to developmental classes based on test scores could have gone straight to a college class and earned a grade of B or better.

The College Board, the company that makes the Accuplacer test, responded to those studies by saying test scores alone should not be used to determine who is ready for college-level classes.

Would I pass the test?

The research got me wondering how someone who already has a college degree would do on such a test.

So I decided to take the Accuplacer.

I have a bachelor's degree from Amherst College, a private, selective, liberal arts school. Amherst didn't make me take any placement tests. The more selective the college, the less likely a student is to take a placement test. The idea is that those students have already proved they're ready, through high school grades and scores on tests such as the SAT and ACT.

There's an entire industry devoted to helping young people get ready for the SAT and ACT. Some parents pay thousands of dollars for their kids to get test prep and tutoring. But if you're someone who has to take the Accuplacer test, chances are no one is paying for fancy test preparation.

In fact, many people who take the Accuplacer have never even heard of the test until they go to their local community college to enroll and are told to walk down the hall and take it. And yet, this may be the highest stakes test they ever take.

I arranged to take the Accuplacer at the Community College of Baltimore County. I arrived on a cold and snowy day, feeling nervous. I last took a test more than 20 years ago.

I met with a counselor who explained the basics. The test is on a computer. It has three parts and all the questions are multiple choice. There's a sentence skills section and a reading skills section, 20 questions each. And then a math section. You start with high school algebra. If you do well on the algebra part, you get kicked up to college math. If you don't do well on algebra, you get a set of questions that test your arithmetic skills.

As I headed in to the testing room, the two women who were signing me in told me they'd tried the test. Both of them tested into developmental math. One tested into developmental reading, too.

The test took me one hour and 48 minutes. You're allowed to take as much time as you want, but the counselor told me to expect to spend about an hour and a half on it. So I went slow.

I was pretty sure I did well on the reading and sentence skills sections, but I found a few of the questions tricky. And on the math, I thought I must have done decently on the algebra part because I had clearly been kicked up to the college math section, and once I got there I was mostly guessing.

I was handed a score report as soon as I walked out of the testing room. Then I headed to a counselor's office to find out what it meant.

I did well on the English sections, but not perfect. A few of those tricky questions got me.

On the college math section, I did not do well. I scored a 27 out of 120.

The counselor told me I'd be in remedial math.

I wasn't really surprised. I never took math in college. My bachelor's degree is in English, and college math was not something I needed to graduate. It's not something I've needed for the kind of math I do in my job either.

But if I wanted to enroll at the Community College of Baltimore County so I could change careers — say I wanted to become a nurse or an art teacher — I would have to pass a college-level math class. And my Accuplacer score indicates I'd need a developmental math class first.

It turns out I wouldn't have to take developmental math though. Someone who already has a bachelor's degree is exempt from taking the placement test. So even though my bachelor's degree included no math at all, I could have used it as proof that I deserve to go straight into college-level math.

This doesn't really make sense. If a certain level of math skill is required for college and the test measures that level of skill, why shouldn't I have to take developmental math like everyone else with a similar test score?

A community college in Baltimore County tackles the problem another way

There is another way to do developmental education that's proving effective for some students. It involves the very thing Bye was originally calling for in Connecticut — let students enroll in college-level classes. But don't let them skip the developmental classes they need. Put them in a class that combines college-level work with developmental help at the same time.

This idea is known in education lingo as the "co-requisite model," as opposed to a "prerequisite model," where there's a strict order in which students take a lower level class before they get to a higher level one.

One of the people credited with the idea of putting developmental students directly into college-level classes is Peter Adams. The idea was inspired by a discovery he made about his students in the late 1980s.

Adams was teaching developmental writing at Essex Community College, now known as the Community College of Baltimore County. He found himself attending commencement ceremonies and not seeing many of his students there.

So, using an Apple IIe computer the department had recently started using as a bookkeeping device, Adams ran a report. It took the computer all night to spit out the results. He arrived in the morning to a pile of green and white striped papers on the floor.

The news was depressing.

More than two-thirds of the students who started in developmental writing never passed English 101, never mind made it to graduation. The obvious explanation was that the students didn't have the skills to make it academically. And for some, that was true.

But the data showed that most of the students who took developmental writing passed the class. And 81 percent of the students who went on to English 101 passed that class, too.

The problem was that the majority of students who started in a developmental writing class never enrolled in English 101. Students weren't failing; they were giving up.

"What we learned was most of the reason that students were not taking and passing English 101 had nothing to do with writing," said Adams. "It had to do with losing their jobs or getting evicted from their apartments or their kids getting sick."

They were quitting school because life got in the way.

Or they were quitting, he realized, because they got discouraged. "A lot of students would say to us, 'You know, I'm not even sure that I am college material,'" said Adams. "What a terrible term, 'college material.' As if human beings come in two categories, those who are and those who are not."

Adams thought what students needed was a faster way of getting through their developmental classes, to reduce the chances that some life event would derail them.

And they needed to feel like they were in college, not in some purgatory waiting to be admitted.

It took him years, but Adams was finally able to convince the college to let him try putting some of the students who tested close to college ready into college-level classes. He called his idea the Accelerated Learning Program.

To see how it works, I visited an ALP class at the Community College of Baltimore County.

There were 19 students in the class. The first hour and a half was a college-level English 101 class. Then nine of the students got up and left, and the rest stayed for a developmental class, taught by the same instructor, Elsbeth Mantler.

Mantler asked the students to write down three words to describe the way they feel about writing.

"Dreadful, fearful and 'Oh my God,'" said one of the students, causing his classmates to burst out laughing. That's how they felt too. One student said she was terrible at punctuation. Another said he was dyslexic and would have failed high school if it weren't for spellcheck on his computer.

The goal of this class is to help students with the basics of grammar and spelling, but not in a skill and drill kind of way, Mantler said. "Skill and drill, meaning having a workbook and working on sentence fragments, is not very effective for students improving on whatever that skill is," she said.

It's the way most developmental classes are taught and it's the way she used to approach developmental writing instruction. But teaching English 101 and developmental writing side-by-side, with the same students, helped Mantler realize that it's better to get all students to write, a lot. Students learn skills better, she said, when they're taught to see the mistakes in their own writing.

Succeeding without all the skills

Jill Harris, an instructor at Middlesex Community College, has a favorite story challenging the notion that there's a basic set of skills everyone needs to succeed.

It involves a former student named Sarah, clearly bright but with terrible grammar and spelling skills. Sarah was in Harris' developmental English class, placed there by way of her low scores on the Accuplacer test.

To pass developmental English, students had to write a paper that got reviewed by the entire English department. Sarah's paper was replete with grammar and spelling mistakes. The department refused to let her move on to college-level classes.

Convinced Sarah was talented and worthy of moving on in college, Harris pleaded to let Sarah write another paper, and the department reluctantly passed her. Harris lost track of Sarah after that.

"Years later, I had a surgery," Harris said, "And I came out from under the anesthetic and there she was, next to me, taking care of me."

Sarah was her nurse.

"She was at Yale," Harris said.

Harris tracked Sarah Keehner down for me and I visited her to hear her story.

It started in elementary school, in special education, a horrible experience for her. "One teacher tried to cut my bangs with a pair of scissors because she told me that's the reason I couldn't read," Keehner said.

She said her special ed teachers let her get away with doing pretty much nothing in school, and then at the end of 5th grade, she was suddenly put back in regular classes. But Keehner had missed out on all those years when other kids were learning the basics of writing.

"When I went to high school and had to take a foreign language is when I learned most of my English skills," Keehner said. "They were talking about verbs, present participles, conjugations and I'm like, 'I don't know what you call any of this stuff.'"

Keehner graduated from high school with no plans to go to college. Her parents hadn't gone. But it didn't take her long to figure out there was very little good work to be had with only a high school diploma. And that's how she ended up in Harris' developmental writing class.

"I'll never be able to spell," Keehner said. "Let's face it: If you're going to hold spelling against me, forget it. I'm in trouble."And if she had to take the Accuplacer test again, Keehner's sure she'd be right back in developmental English. But she didn't have to take the test again, and she succeeded in college without good grammar and spelling skills. She graduated with honors and went to nursing school.

Learning medical language was hard for her, partly because she's dyslexic. But she learned ways around it. In nursing school, for example, Keehner said she listened carefully and took lots of notes instead of reading the textbooks.

The way Keehner sees it, the Accuplacer test and the developmental English class were hoops she had to jump through to prove she was worthy of a college degree.

Does accelerated learning work?

There's a lot of attention being paid in education circles to accelerated learning programs like the one at the Community College of Baltimore County.

Students who start in ALP are twice as likely to pass English 101 as similar students who start in a traditional developmental writing class. Part of the reason is obvious: students are getting both their developmental class and their English 101 class out of the way in the same semester, narrowing the window on the possibility of a life event knocking them off track.

And even if life events do intrude as students move through subsequent semesters, the data show students who start in ALP are more likely than students who start in a traditional developmental class to make it to graduation. Adams thinks it has to do with motivation and self-confidence.

"What we say when they arrive and we put them in these developmental courses is, 'we think you're a terrible writer,'" he said. "And then they produce terrible writing as a result. And if we challenge them they rise to the occasion much more often than we expect."

There are dozens of other colleges and universities trying accelerated approaches to developmental education. But most of the research focuses on people whose test scores show they are close to being ready for college-level classes. What about students who are way behind?

Little research has been done into how best to help those students. And it's not clear that current approaches to developmental education are getting in every student's way. In fact, some research shows that students placed in the lowest level developmental classes benefit from those classes.

The state of Tennessee is experimenting with the idea of putting everyone who needs remediation into co-requisite classes, and there's some early evidence that it may help even those with very low test scores. But it may be better for some students to be kept together in stand-alone developmental classes.

That's what Latasha Gandy said she needed after graduating from Arlington High School in St. Paul.

"When it came to my English and reading courses, I needed that remediation, because I never got it in high school," Gandy said.The spiffy new high school she went to did not prepare her or her classmates for college, she said. "The longest paper I remember writing was two pages," she said.

She's grateful she wasn't put in a college-level English class right away. When she finally got to college classes, she was shocked to find that some students had to write 10-page research papers in high school.

A recent analysis of test score data nationwide shows that by sixth grade, students in the poorest school districts are already four grade levels behind students in the richest districts. The college remediation divide begins early and more often than not ends in students like Gandy giving up.

But Gandy didn't give up. She got through her developmental classes — an entire year of them — and went on to complete a bachelor's degree. Now she's executive director of an education reform group that is pushing to make remedial education free.

Bachelor degree attainment by income level

But the biggest cost for the majority of students who end up in developmental classes isn't tuition. It's the long-term cost of not getting a college degree. The system that is supposed to be helping them is more often getting in their way, Adams said, creating a big barrier within American higher education that disproportionately affects low-income students of color.

"In higher education we do lots of important things," Adams said. "We produce astronauts and poets and dancers and computer programmers. And all that's important. But if your focus is on the role higher education plays in democracy and trying to make this a country of equal opportunity, of the American Dream, of closing the gap between the very rich and everybody else, then the most important thing we do is developmental education. And it's really crucial that we fix it."

Correspondent/Producer: Emily Hanford

Editor: Catherine Winter

Web Editor: Dave Peters

Web Producer: Andy Kruse

Technical Director: Craig Thorson

Associate Producers: Suzanne Pekow, Ryan Katz

Research and Production Fellows: Alex Baumhardt and Lila Cherneff

Executive Editor and Host: Stephen Smith

Project Manager: Ellen Guettler

Managing Director, Editor-in-Chief: Chris Worthington

Special thanks: Liz Lyon, Tom Bailey, Katie Zaback

Main illustration by Lila Cherneff.

Support for this program comes Lumina Foundation and the Spencer Foundation.

A note of disclosure: The Spencer and Lumina Foundations supported some of the research that was referred to in this program. But the foundations had no influence on our coverage.

Feedback

We're interested in hearing what impact APM Reports programs have on you. Has one of our documentaries or podcasts changed how you think about an issue? Has it led you to do something, like start a conversation or try to do something new in your community? Share your impact story.