Two centuries of school discipline

How to discipline students has been debated in American schools since the country was founded.

Discipline has been part of American schooling from its beginning. The debate has been how it should be achieved.

Some educators have believed in harsh discipline methods like corporal punishment, suspension or expulsion. Others have sought less onerous means.

Either way, discipline was considered key to learning in the early days of the nation.

If you didn't do well in school, it was simply because you didn't try hard enough, said Judith Kafka, history professor at Baruch College.

The teacher's job was not only to teach basic reading and arithmetic. "School would train children how to behave, how to be members of society, be good citizens, be responsible," Kafka said.

Teachers commonly used corporal punishment in the form of a switch, cowhide or ruler, Kafka has written. Students knelt on sharp objects or stood for long periods of time.

The authority of teachers to discipline students came from a legal term from English common law, "in loco parentis," which translates to "in the place of a parent." This gave teachers a lot of discretion.

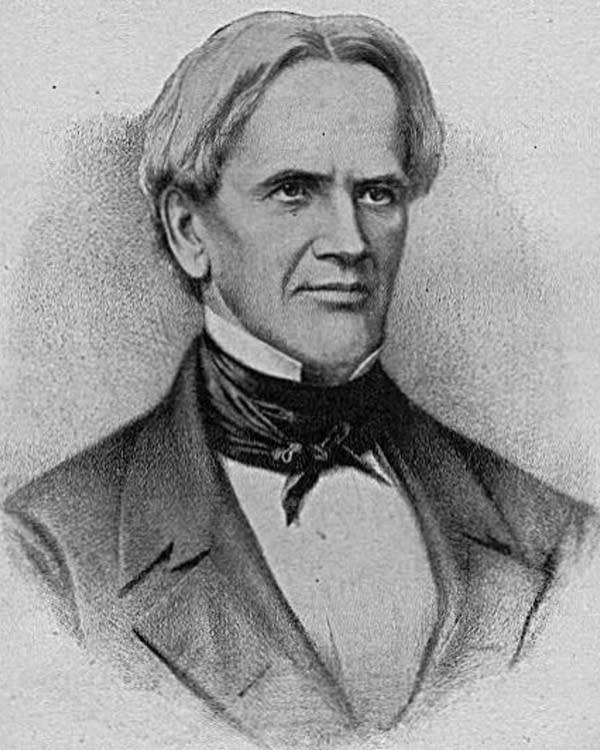

Yet many criticized corporal punishment for its ineffectiveness. Education reformer Horace Mann called it "a relic of barbarism" and argued that students should learn how to monitor their own behaviors.

Still, educators agreed that discipline was an inherent part of a teacher's job.

That started to change around the turn of the century. Between 1890 and 1918, high school enrollment increased by 711 percent. The traditional one-room schoolhouse gave way to multiple, stratified classrooms and a principal who oversaw them. This new hierarchy of adults meant the principal, not the teacher, started to dole out discipline.

After World War II, teachers began to unionize. "Teachers wanted discipline to be put in their contracts to be very clear what they were responsible for," Kafka said.

Teachers wanted to focus on teaching, not behavior problems. And bad behavior was seen as a major issue at the time.

The 1950s brought a widespread fear that kids were out of control — under the influence of comic books and movies and rock and roll. Newsreels and Hollywood warned of a crisis of juvenile delinquency.

The popular 1955 film Blackboard Jungle depicted teenagers run amok in the classroom.

Recent research has cast doubt on the supposed trend of rising juvenile crime at the time, but standardized rules regulating school discipline soon followed. Personal judgments of individual teachers waned; their power from "in loco parentis" died. Administrators, principals, and even social workers took on more responsibility for disciplining students.

In 1975, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Goss v. Lopez that schools could not suspend a student without a hearing. It was a major victory for students' rights. Yet just a few years later, in Ingraham v. Wright, the court ruled that corporal punishment in schools is constitutional. Today, it remains legal in 19 states.

The crack epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s triggered a renewed fear of gang violence and greater efforts to punish criminals both inside and outside of schools. A panel appointed by President Reagan called for a return to "good old-fashioned discipline," warning that "for many teachers, schools have become hazardous places to teach and definitely places to fear." Congress passed the Gun-Free Schools Act in 1994, signed by President Bill Clinton. It began the "zero tolerance" era in American public schools. Under zero tolerance, a student who violated school rules faced mandatory penalties, adopted from the "broken windows" theory of policing. Schools increasingly deployed police officers to monitor their halls.

"The theory was that by providing severe consequences to minor infractions, it would send a message to students that disruptive behavior was unacceptable," said Russell Skiba, professor of educational psychology at Indiana University.

Zero tolerance was supported by key education stakeholders.

Albert Shanker, the president of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), wrote in support of zero tolerance laws, saying education reform would be impossible without them. "The truth of the matter is that none of these changes will achieve what we want unless schools are safe and ordely places where teachers can teach and students can learn," he wrote.

But research has shown in recent years that zero tolerance didn't succeed in making schools safer and did result in racial gaps in school discipline.

With prodding from the federal government, many schools have more recently turned to approaches that de-emphasize suspensions and expulsions and instead focus on relationships within the school and harm done by bad behavior, approaches often referred to as restorative practices.