The questionable science of tire track and shoe print analysis

They can rule out a suspect, but shoe prints and tire tracks in the dirt lack solid standards for use as forensic evidence.

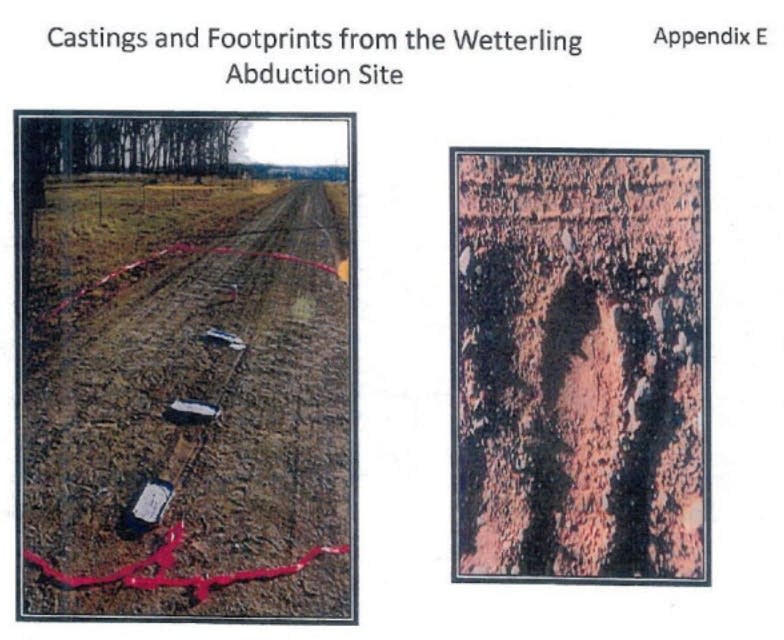

On the morning of Oct. 23, 1989, investigators gazed down at the myriad tire tracks and shoe prints crisscrossing the rural driveway near where Jacob Wetterling was last seen the night before. The police walked the edges of the loose gravel, where a bloodhound had traced the 11-year-old's scent. But trying to read the scribble of markings on the road was like trying to get meaning from the creases on someone's palm.

Presumably, some of the tracks and prints were made by the perpetrator. Figuring out which, with no idea of the kind of shoe he was wearing or the type of tire on his car, if he even had a car, was the objective. The police needed the gravel to tell them a story.

It was dry and unseasonably warm on the night Wetterling was kidnapped by a man wearing a mask and holding a gun. He and the gunman had vanished, virtually without a trace. "We just have no evidence," Stearns County Sheriff Charlie Grafft said at the time. There were the bikes and scooter the children were riding, which lay in a ditch. And there was whatever could be discerned from the long gravel driveway, which had been driven and walked on by an unknown number of people.

The problem with tire tracks and shoe prints, which, like fingerprints, fall into the forensics category of "pattern evidence," is that they're difficult to identify. They are also tricky to document through casting, difficult to interpret, and even tougher to match to a potential suspect. An investigator can't simply upload an image of a tire track to a computer, hit a button, and expect a readout containing the make, model and owner of the car that created it. That's the reality now, as it was in 1989, the year the World Wide Web was invented and Apple introduced its first portable computer, which weighed 16 pounds.

For an investigator to declare a match, a print or track has to contain more than just the general characteristics created by its manufacturer. There are millions of Nike and Reebok shoes and just as many Michelin and Goodyear tires. The police must identify a tread pattern, as well as a set of unique or individual characteristics within the track or tread, such as markings left by a nail stuck in a tire or signs of a shoe that's worn at the heel. Then, they have to find the tire with that very nail in it or the shoe with the matching wear pattern. An exact match rests in the eye of the beholder.

"This is completely subjective," said Mary Moriarty, the chief Hennepin County public defender and an expert in forensic evidence. She said there are no rules governing how many individual characteristics must be present before a match is declared. Nor are there established error rates. "I mean, how many people step in gum?" she asked. "They don't have any database that tells you that. There's no science behind that. There is no agreement within the community of tread or footwear examiners that there have to be so many individual characteristics (present), Moriarty said. "So I might look at it and say, 'Oh, there just isn't enough there,'" she said. "And you might look at it and say, 'Well, I think there is enough there to go forward.' That's a problem, that there are no standards."

This sort of pattern evidence has fallen out of favor among criminal justice experts in recent years to the point that it's widely considered unreliable, more often used to rule suspects out than to rule them in.

"There has been a sea change in how people in the criminal justice community view forensic science," Moriarty said. "And the real change came about when DNA came into the picture. DNA is based on scientific principles and it's based on population statistics. Scientists who did it started looking at the other forensic disciplines, questioning what kind of science was actually behind them, and it turned out there was very little."

One of the most prominent blunders in the field of pattern evidence took place in 2004. An attorney named Brandon Mayfield was wrongly accused of a series of commuter-train bombings in Madrid based on the opinions of four fingerprint experts, who agreed that a print found on a bag containing detonators belonged to him. His home was searched and bugged before he was finally cleared. That case prompted Congress to ask the National Academy of Sciences to assess the state of forensics in the criminal justice system.

The resulting 2009 report was critical of most forms of forensic evidence, noting that "faulty forensic science analyses may have contributed to wrongful convictions of innocent people. This fact has demonstrated the potential danger of giving undue weight to evidence and testimony derived from imperfect testing and analysis." The report pointed out a lack of consistency between and within the various forensics disciplines in terms of funding, access to analytical tools and well-trained staff, certification, accreditation and oversight.

Of shoe print and tire track evidence in particular, the report said, "The educational background of forensics scientists who examine shoeprints and tire track impressions runs the gamut from a high school diploma to scientists with Ph.D.s. Identifications are largely subjective and are based on the examiner's experience." It documented the lack of a "defined threshold that must be surpassed" in order to establish "the probability that the impressions were made by a common source." While experts argue that they gain a sense of those probabilities through experience — they know it when they see it — "it is difficult to avoid biases in experience-based judgments, especially in the absence of a feedback mechanism to correct erroneous judgment."

Investigators in October 1989 knew that when Jacob Wetterling was abducted, he was wearing a pair of size-5, high-top Nike sneakers with logos on the bottoms. They found prints on the driveway that seemed to match the shoes. They saw one print that seemed to dig deeper than the others and thought that could mean Jacob had resisted being dragged into a car. Nearby, the police found another set of shoe prints they believed belonged to the abductor. They also discovered a set of tire tracks that appeared to be connected to the case.

They photographed and made casts of the prints and tracks. Casting is a tricky process that can damage three-dimensional, or "plastic," prints. A liquid — usually powdered dental stone mixed with water — is poured into a print, testing its delicate sand walls.

The police searched for a match by issuing descriptions of a series of suspicious vehicles that varied greatly in size, color, and style. They looked for a small red car, a tan van, a white Chevrolet Celebrity or Citation, a tan Lincoln Town Car, a maroon Catalina or similar model, a red-orange station wagon, a dark brown station wagon, a dark blue four-door and others.

By late 1989, investigators had several suspects, including Danny Heinrich, who recently confessed to the murder in gruesome detail as part of a plea deal. Back then, he voluntarily turned over a pair of tennis shoes and the rear tires from his 1982 Ford EXP. Heinrich's shoes and tires had both been purchased at Sears, though the tires, from the company's SuperGuard Response line, were manufactured by an outside company, Armstrong.

The casts from the crime scene were sent to the FBI for analysis, to see if they matched Heinrich's vehicle and shoes. But the lab could describe them only as a general match. An affidavit to support a later search warrant said that an FBI examiner in 1990 found the shoe impression from the crime scene "corresponds in design" to Heinrich's tennis shoe but noted that "due to lack of sufficient detail," an exact match could not be made. Likewise, Heinrich's tires were found to be "consistent with the tire impressions found at the Wetterling crime scene" in size and tread design. But they were "not an exact match."

Since the matches were not scientifically exact, they weren't evidence enough to arrest Heinrich back in 1990. "Consistent with" means very little, said Moriarty. "'Consistent with' simply means it cannot be ruled out."