Reporter Madeleine Baran, host of the podcast In the Dark, writes the story of how the 1989 abduction of Jacob Wetterling in central Minnesota baffled local, state and federal investigators for years. In four chapters, she reports why it shouldn't have.

December 30, 2016

Prologue

It was around 8:30 p.m. on Oct. 22, 1989, when 11-year-old Jacob Wetterling put on his red hockey jacket and left his house to bike to the video store in the dark with his younger brother and his best friend.

It was just a short bike ride on a dead-end street that led from the edge of the small town of St. Joseph in central Minnesota to the brown split-level house where Jacob lived with his mom, dad, brother and two sisters.

But Jacob never made it home.

On the way back, a masked man appeared on the road. He grabbed Jacob and told the other boys to run and not look back.

What happened that night would lead to one of the largest and longest law enforcement investigations in the history of the United States. The case involved nearly 100 officers from the FBI, the state crime bureau, the Stearns County Sheriff's Office and the National Guard — along with thousands of volunteers who combed the cornfields and ditches in rural Minnesota.

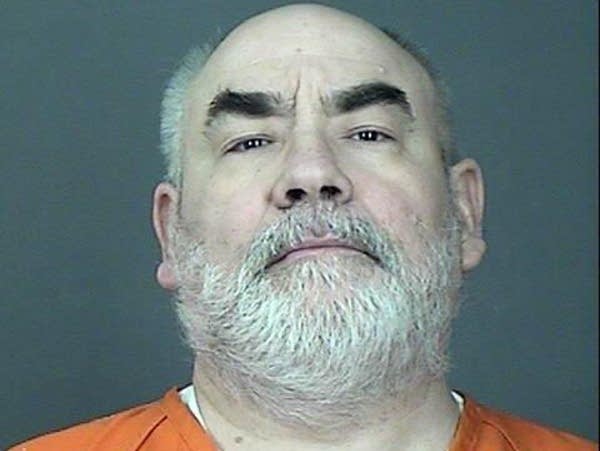

The Wetterling case went unsolved for nearly 27 years, until four months ago, when a man facing 25 counts of child pornography confessed to the crime as part of a plea deal and led authorities to Jacob's remains.

Few people questioned the actions of law enforcement. The lead agency — the Stearns County Sheriff's Office — assured the public it was doing everything it could and that the case was the worst kind of mystery — one with few clues or clear suspects. Hundreds of news stories describe how officers sifted through thousands of leads, interviewed everyone who might have even the slightest bit of helpful information, and conducted an exhaustive, methodical search for this missing boy. There was nothing else they could do. The case was practically unsolvable.

The story was easy for people to accept, perhaps because it was so familiar. It's the plot of hundreds, maybe thousands of true crime books, movies and TV shows — the tireless detective trying to solve the perfect crime.

But the story is just that — a fiction.

The Wetterling case wasn't the perfect crime. It was a botched investigation. An APM Reports investigation found that officers with the Stearns County Sheriff's Office failed to conduct some of the most basic police work in the critical first few hours after Jacob disappeared. They mishandled a confrontation with a key suspect. And, after more than a decade of no success, they focused on the wrong guy — and in the process, turned one of their best witnesses into a top suspect. All along, the person who took Jacob was right in front of them.

The failure to solve the case changed the lives of millions of Americans. Parents across the Midwest stopped letting their children go outside at night. The case fueled a national hysteria over "stranger danger." Kids watched public service announcements about not taking rides from strange men in white vans. Parents started fingerprinting their kids in case someone snatched them.

The panic culminated in a federal law, the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act, that requires all states to maintain registries of sex offenders. Over the years, registries expanded to include people who urinated outside and people who texted nude photos of themselves. Children started being placed on sex offender registries. There are now about 850,000 people on sex offender registries in this country, according to the best available estimate. That's about one in 380 people.

The Wetterling case was a failure, but it's not unique. Every year, thousands of serious crimes all across the United States go unsolved, often with no public attention, let alone outrage.

The agency in charge of finding Jacob Wetterling — the Stearns County Sheriff's Office — cleared just 20 percent of its major crimes from 1971 to 2014. It cleared 59 percent of murders, according to the state crime bureau.

The clearance rates in Stearns County are startling, and they put Stearns County in the bottom third of comparable sheriff's offices across the country for murder, but they aren't the lowest in the nation — not by a long shot.

There are law enforcement agencies in the United States that clear fewer than 10 percent of their major crimes.

It's rare for anyone to be held accountable for these failures. Law enforcement in the United States is a local matter, handled by thousands of agencies — police departments, sheriff's offices and state crime bureaus. The nation's approach to crime is so decentralized that no one even knows the exact number of police departments in this country. There are no national benchmarks for crime clearance rates, no national mandatory standards for how to investigate a crime, no routine federal intervention to force law enforcement agencies to improve, and few studies on how to improve a detective's chance of solving a case.

As a result, you could live in a place that hasn't solved a single crime in 50 years, and nothing would happen.

This was the world Jacob disappeared into.

The crime

I went to meet Jacob's parents, Patty and Jerry Wetterling, earlier this year, seven months before the case was solved. They still lived in the same cozy brown house in St. Joseph and continue to do so now. On the front of the house was a string of lights that spelled out the word "hope."

Patty answered the door. She's petite, with bright blue eyes and short blonde hair. She offered me some coffee, and we sat down at the kitchen table.

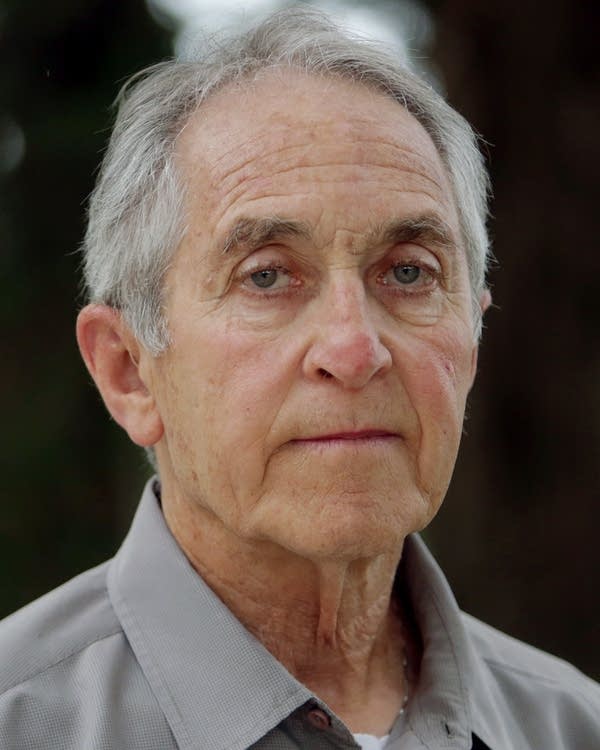

Jerry got home a few minutes later from his job as a chiropractor. He's tall, with a short white beard, and he has the look of a college professor or maybe a therapist.

In 1989, the Wetterlings were a young family. Patty was 39. Jerry was 41. Their four children were ages 8 to 13. The Wetterlings were bright and outgoing and involved in everything. Jerry led the local chapter of the NAACP.

Jacob was in the sixth grade. He was 5 feet tall and skinny with dark brown hair. He had blue eyes, like his mom. He loved watching football and playing hockey and baseball with his friends. He pretended to be a sports announcer when he watched games on TV with his dad. He wanted to be a veterinarian when he grew up.

"Jacob was very passionate," Jerry, his dad, said. "What he would do, he would do 100 percent and really be into it."

Patty recalled how Jacob persuaded them to get a puppy after he broke his arm. "He just knew it wouldn't hurt if he had a puppy," Patty said, laughing. "I was a pushover."

Jacob joked around a lot. He tried to teach the new puppy how to drink water by lying on the floor and drinking out of a bowl.

He loved playing with his brother and sisters. His youngest sister, Carmen, had two imaginary friends, and Jacob used to talk to both of them and make sure they were OK.

"He was a good spirit," Patty said.

Oct. 22, 1989, was a Sunday, but the kids were to be off school the next day. By late October, this part of Minnesota is usually well on its way to winter. But this day was in the 70s, and there were lots of kids outside, running around wearing shorts and tossing footballs. There was a polka festival in town. It felt like one of those long, glorious, late-summer days.

The town of St. Joseph, home to about 3,000 people, was considered a safe place to live. Kids rode their bikes everywhere. They played in the cornfields. Some kids would build fires by the river and roast hot dogs. The police chief didn't even carry a gun.

That morning, Jacob and his dad, Jerry, went fishing. They came back home and everyone gathered around the TV to watch the Minnesota Vikings play the Detroit Lions. Later that afternoon, they went skating at an indoor ice rink.

In the evening, Jacob's parents headed out to a gathering at a friend's house about 20 miles away. Their oldest child, Amy, was at a friend's house.

Jacob stayed home with his brother, Trevor, 10, and his younger sister Carmen, 8. His best friend Aaron Larson came over for a sleepover. They ate a pizza and hung out for a while, and at some point the boys came up with a plan to rent a movie from a nearby Tom Thumb store.

But first, they needed permission. The boys had never biked to the store that late before. So Jacob's brother, Trevor, called their parents.

Patty said no. It was too dark.

Then Trevor asked to talk to his dad.

Jerry wasn't sure about the boys' plan, either. "My whole concern was a car hitting them, being seen in the dark," he said.

Trevor told his dad that he would carry a flashlight and Jacob would wear a reflective vest.

After hearing all that, Jerry said yes.

Jacob called the next-door neighbor, 14-year-old Rochelle Jerzak, and asked her to babysit their younger sister, Carmen.

Rochelle came over and watched as Jacob put on an orange reflective vest over his red hockey jacket. Then the boys headed out.

The route the boys took that night was pretty simple. The Tom Thumb store was about a 15-minute bike ride into town, up a dead-end country road that leads from the cul-de-sac where the Wetterlings lived into town. There's not much in between — just some cornfields and some woods, and then closer to town, a few blocks of houses.

As they biked up the road, the boys passed a long gravel driveway. And somewhere close to that driveway, they heard a rustling sound in the corn.

They got to Tom Thumb and rented "The Naked Gun." Then they headed back home.

They passed the few blocks of houses, and the lights of the town faded away.

They biked past woods and the cornfields. There were no sidewalks and no street lights. Not even the moon was out.

The only light came from a flashlight that Trevor flashed in front of them.

They approached the long gravel driveway, the spot where there'd been that rustling sound earlier.

They were almost home.

All of a sudden, a man appeared on the road and started walking toward them. He was dressed all in black. His face was covered with something dark. It was hard to tell what. The man told the boys he had a gun. He ordered them into the ditch and told them to lie down.

At first, Jacob's best friend Aaron thought it was some kind of prank. Maybe an older kid was messing with them, he thought. Maybe it was an early Halloween joke.

The man told Trevor to turn off his flashlight. He asked Trevor his age. "Ten," Trevor said.

The man told Trevor to run as fast as he could into the woods or he'd shoot.

Next, the man turned to Aaron and asked him his age. "Eleven," Aaron said. The man grabbed Aaron in the crotch and groped him.

The man asked Jacob his age. "Eleven," Jacob said.

The man told Aaron to run as fast as he could into the woods or else he'd shoot. Aaron took off running.

By the time he looked back, the man and Jacob were gone.

It was about 9:20 p.m.

Jacob was never seen alive again.

The circle

When I think about that first night, I think about the spot on the side of the road where Jacob was taken, and I draw a circle around it, around Jacob and the abductor.

At that moment, the circle was still small. Jacob was right there.

But then I picture that circle slowly expanding, as the man and Jacob get farther and farther away, as the seconds and minutes tick by.

If law enforcement was going to find Jacob, they needed to act quickly, before the circle got too big.

The most comprehensive report on child abduction murders lays out the grim reason why.

Most children in these cases are killed within the first few hours. By the end of the first five hours, 85 percent of kids are dead. And by the end of the first 24 hours, in almost every case, the child has been killed.

Rochelle, the babysitter, was watching TV at the Wetterling house with Jacob's younger sister when Trevor and Aaron ran in screaming. Trevor yelled, "Someone took Jacob! There was a man with a gun and he took Jacob!" Rochelle was terrified. "I didn't know what to do," she said. "The first thing I did was pick up the phone and called my Dad and had him come right over."

Rochelle's dad, Merle Jerzak, called Jacob's parents and then 911.

It was 9:32 p.m. Jacob had been missing for about 15 minutes. The circle was still small.

On the 911 call (full transcript), Jerzak tried to explain what had just happened and then he put Trevor on the phone to describe the man who took Jacob. "He was like, sort of, he was like a man," Trevor said. The dispatcher asked if the man was large. "Sort of," Trevor said.

Trevor told the dispatcher that a man had stepped out of the darkness. The boys didn't recognize him, and they didn't see or hear a car anywhere. The man's face was covered with something dark, maybe black nylons. He sounded like he had a cold. In the dark, that was all the boys could make out.

On the other end of the 911 call was a dispatcher for the Stearns County Sheriff's Office. The dispatcher put out a call on the radio.

Deputy Bruce Bechtold was the first to respond. He was a new patrol officer — he'd been on patrol for just a few months, after a stint working in the county jail. That night, he was in his squad car a couple of miles away.

Bechtold pulled into the Wetterlings' driveway at 9:38 p.m. Jacob had been missing for about 20 minutes.

The man who took him couldn't be very far away.

Bechtold found himself talking to two terrified boys. He tried to convince them to get in his car and show them the spot where Jacob was kidnapped. But the boys didn't want to go back out in the dark. So Jerzak, the babysitter's father, offered to go with them, and the boys agreed.

Meanwhile, Jacob's parents, Patty and Jerry, were on their way back home.

The 20-minute drive seemed to take forever. Jerry drove, and Patty kept urging him to go faster. "In my mind, he was going 10 miles an hour and I'm like, 'Speed. Hurry up.' He said he didn't want to get stopped by the police. I said, 'Well, we'd have a police escort, so just drive.'"

In the panic, Patty said something she regretted.

"Well, who told them they could go to the store?" she said. "I did," Jerry said. "So if you want to be mad at somebody, be mad at me."

The Wetterlings arrived home to find the kids panicking. Jacob's brother, Trevor, talked nonstop, trying to explain to his parents what had just happened. Jacob's best friend Aaron stood in the corner biting his nails. "It was like he wanted to disappear," Patty said.

Investigators from the Stearns County Sheriff's Office sat the boys down at the kitchen table. They wanted to make sure it wasn't a joke.

Child abduction is one of the rarest crimes. It almost never happens. The scene the boys were describing sounded more like a movie than real life.

Patty remembered the officers asked the boys questions like, "Are you sure you weren't playing with a gun and Jacob got hurt and you're afraid to tell?" and "Are you sure Jacob didn't just run away and you're trying to buy him some time until he gets where he's going?"

No, the boys said. It really did happen. A man with a gun took Jacob.

Troubled by unsolved crimes

The case fell under the jurisdiction of the sheriff's office, the agency that handles most major crimes outside Stearns County's biggest city, St. Cloud.

The county it was responsible for patrolling is more than twice the size of Los Angeles, but in 1989, it was home to just 118,000 people.

Stearns County is a collection of small towns surrounded by farmland. It's home to farmers and construction workers and laborers who make their money hauling granite out of the ground, processing it and shipping it across the country to be made into kitchen countertops, so it's possible that you have a little piece of Stearns County in your house right now.

Although Stearns County is mostly rural, the sheriff's office isn't tiny. In 1989, it had a budget of $1.6 million and a force of approximately 20 full-time patrol officers, four detectives, four sergeants, a patrol captain, a patrol lieutenant, a chief deputy and a sheriff. It also had dozens of other employees who worked in the jail or in the main office.

The sheriff was a 62-year-old man named Charlie Grafft.

If you picture a small town sheriff, you'll probably come pretty close to picturing Sheriff Charlie Grafft. The sheriff wore brown pants, a brown tie and a white button-up shirt with a shiny badge. His hair was dark and slicked back, and he was fond of wearing dark, tinted aviator sunglasses. Grafft died in 2003.

He'd started out in law enforcement 37 years earlier, as the only police officer in Waite Park, the town next to St. Joseph, where the Wetterlings lived. Back in the 1950s, there was no 911, no radio dispatch, no squad cars and no other officers. Grafft was the only one. Every night, out on patrol by himself, he'd drive by his house to see if the porch light was on. It was his wife's way of letting him know that someone had called to report a crime.

By the time Grafft was elected sheriff in 1978, officers were using radio dispatch in their squad cars. It was a big help, but Grafft felt uneasy about it. He worried that a savvy criminal could easily listen in to the dispatch and hear an investigation unfold and use the information to evade police.

Grafft asked the county board to spend $35,000 to buy equipment that would prevent the public from listening. The board rejected his request. It was too expensive, it said.

Grafft had won election on a promise to do a better job of solving crime than his predecessor, Jim Ellering. In Ellering's four-year term, the Stearns County Sheriff's Office had cleared just 10 percent of its major crimes.

The list of unsolved crimes that Grafft had inherited included several murders that had made headlines across the state.

In 1974, two girls, Mary and Susanne Reker, went out to buy school supplies. They didn't come home. When their father went to the police station to report the girls as missing, no one took it seriously, the girl's mom, Rita Reker, told me earlier this year.

Twenty-six days after the girls disappeared, they were found stabbed to death in a quarry on the outskirts of town.

Because the bodies of Mary and Susanne had been found outside city limits, the case passed into the hands of the Stearns County Sheriff's Office.

"I guess we expected a big time investigation to start from there on," Rita Reker said. "But our case could not have happened at a worse time in history for an investigation."

She told me that her girls' bodies were found five weeks before the sheriff's election in November. "They were busy with the elections and all, before they could really get serious about an investigation," she said.

From there, the Reker case got tangled up in the politics of the sheriff's office. The lead investigator, Lawrence Kritzeck, refused to let the sheriff even look at the case file. Rumors spread that Kritzeck wanted the case so he could use solving it to get elected as sheriff.

Four years later, the sheriff finally managed to pry the case away from him, but Kritzeck held onto a pair of eyeglasses that had been found at the crime scene. He kept them in his desk drawer. No one found them until he died, nine years after the Reker girls were killed.

A newspaper story about the case published in 1977 summarized the investigation this way: "The original police investigation of the Reker murders will never be used as a textbook example of how solve a homicide or how to deal with the victims' family and friends."

The murder of Mary and Susanne Reker was never solved.

The cases kept coming.

Two years after the Reker girls were killed, a bomb exploded at a post office in the tiny town of Kimball, also in Stearns County. The blast killed the assistant postmaster. Authorities never solved the case.

Then, 10 days before Christmas in 1978, a crime happened that shocked the community in a way that nothing else had.

'Let's not screw this one up'

In the middle of the night, a man entered a rural farmhouse where a single mother named Alice Huling lived with her four children. The man cut the phone line and went into Alice's bedroom. He hit her with some kind of heavy object, shot and killed her, and then headed upstairs and killed three of her children in their beds. He aimed his gun at the remaining child, 11-year-old Billy Huling, but the shot missed and hit the pillowcase instead. Billy kept absolutely still, and the man left.

Jim Kostreba was the first officer called to the scene. He would go on to work on the Jacob Wetterling case and was elected sheriff of Stearns County in 1990.

"I can remember driving up to the house," Kostreba told me. "I can remember how cold it was, how bright the moon was shining. It was a beautiful evening, a beautiful night. And I think what I remember most about stepping inside the door was the smell of the gunshot powder. I could still smell the gunshot powder in the air. Then I knew that something terrible had happened at that house."

Kostreba peered into the bedrooms and saw the three kids and their mother dead.

A young EMT named Steve Mund, who would later work as a detective on the Wetterling case, showed up a short while later. Mund watched as investigators arrived to collect evidence and take photos. In some of the photos, you can see the kids' toy cars scattered around.

Mund described what he saw in a written statement filed in court years later. "When the Sheriff arrived he asked what happened and what was being done," Mund wrote. "He appeared to be very nervous or agitated. Then he made a statement that I found very interesting. 'Let's not screw this one up like the Reker case.'"

Mund saw a state investigator pick up the phone in the Huling house before dusting it for fingerprints. A captain from the Stearns County Sheriff's Office realized the mistake and "said something like, 'Oh well,'" Mund wrote.

The case didn't start out strong, but four days later, authorities had a suspect in custody, a man named Joseph Ture who lived in his car and had been harassing waitresses at a nearby truck stop. Sheriff's deputies searched Ture's car and found a metal club, a toy Batmobile car, and a small brown diary with the names, addresses and license plate numbers of waitresses.

Two officers from the Stearns County Sheriff's Office, Kostreba and Detective Ross Baker, went to interrogate him.

Ture was angry and wanted to know why the officers wanted to talk to him. "I'm not a crook or nothing," Ture told them, according to a transcript of the interrogation. "I don't go around raping girls or whatever. I have a few phone numbers, fine. I am getting kind of old for chasing puss around."

Even if he had a few dates with some waitresses, he said, "It don't mean I'd take them out or kill them or whatever."

The officers put some items from Ture's car on the table in front of him — the metal club and the toy Batmobile.

They asked him about the Batmobile.

"It's mine," Ture said. "I have grandkids."

Ture was just 27 years old. It didn't make sense.

When the officers pressed him, Ture changed his story. "I'm an uncle, or whatever," he said.

The more the officers talked about the toy Batmobile, the angrier Ture got. He asked the investigators, "What difference do a couple of toys make?"

"Well, it might make a lot of difference," an officer replied.

Finally, the officers left. Ture stayed in jail. And over the next few days, the officers had the seats and door panels torn out of Ture's car to look for a gun, but they didn't find one. They went to the place where Ture had worked as a mechanic and looked at his time card. It didn't give Ture an alibi.

They questioned Ture again and brought up the Huling murders directly. Ture responded by asking them all kinds of questions about what kind of evidence they had, whether they'd found the gun, and whether anyone had identified him as the murderer.

But there was one thing the officers didn't do.

They didn't take a closer look at the toy Batmobile that they found in Ture's car. They didn't bring it to Billy Huling, the boy who survived, and ask Billy if he owned a toy Batmobile like that one, and then check the house to see if it was missing.

A week or so later, without any evidence to hold him, a judge let Joseph Ture go.

Once Ture got out, he broke into a house and killed a teenage girl who was home alone. Then he kidnapped a waitress named Diane Edwards from the side of a road in West St. Paul, drove her to a secluded area, sexually assaulted her and killed her. He started driving around Minneapolis late at night, looking for women outside. He grabbed at least two women off the street and raped them, and he kidnapped and raped a 13-year-old girl. He also tried to kidnap at least two other women, but they got away. One escaped by smashing a lit cigarette in his face.

Ture's crime spree didn't end until 1980, and it wasn't the Stearns County Sheriff's Office that put an end to it. It was the Minneapolis police. Officers arrested Ture for several rapes, and while Ture was in custody, he was charged with murdering Edwards, the waitress. He received a life sentence and has been in prison ever since.

In the mid-1990s, a state cold case unit revisited the Huling case, and officers went to find Billy Huling, the boy who survived the murders. By that point, he was grown up with a family of his own.

One of the people involved with the case told Billy there was some evidence they wanted him to look at.

And Billy replied, out of nowhere, "Did you guys find my Batmobile?"

State investigators quickly built a case based on the same evidence that the Stearns County Sheriff's Office had known about since 1978 — the metal bar and the toy Batmobile.

Twenty-one years after Ture had killed four members of the Huling family and after he'd gone on to kill at least two more people and sexually assault at least three more, a jury finally convicted him of the Huling murders.

I asked Kostreba, the officer who questioned Ture in 1978, why he hadn't asked Billy Huling about the toy Batmobile.

Kostreba sighed. "That's a question that comes up in my mind many times," he said. "It's something I think about quite a bit, because it's something that should have been done and it wasn't."

Kostreba said, as far as he knows, no one made any changes at the sheriff's office to prevent this kind of mistake from happening again. As best I can tell, there was no formal training or review at the sheriff's office about how to learn from the Huling case or any of the other unsolved crimes in the 1970s.

But the problems in the sheriff's office did get the attention of a local politician, State Rep. Al Patton.

Patton retired years ago. "Criminy sakes alive, Jesus Christ," he said, when reached on his phone a few months ago. "After almost 40 years, we're going to stir up this cat again?"

Patton told me how in the 1970s, he started hearing about problems with evidence handling, in-fighting among deputies, a lack of training, and failed investigations in the Stearns County Sheriff's Office.

"Crimes were being committed that were unsolvable for the education and the background of the individuals holding the position of sheriff," he said.

The way Patton saw it, voters didn't know enough to be able to choose the best candidate for sheriff. He proposed a bill at the Minnesota Legislature in 1979 that would have gotten rid of elections for sheriffs and turned the job into an appointed position.

"The reaction to the piece of legislation I introduced was not mixed," he said. "It was very straight forward. It was resisted."

The bill never came up for a vote. Patton's effort had failed. It still bothers him. "There has to be an element in there to have accountability," he said. "And when accountability is not there, disastrous things happen."

Grafft campaigned on a promise to fix the problems in the Stearns County Sheriff's Office, but once he was elected, the cases kept piling up. In 1981, an 81-year-old woman named Myrtle Cole was found stabbed to death in her bed at her home in Fairhaven, Minn.

Officers had found a bloody handprint on the pillow case next to Cole's body, but no one took a handprint from her body to see if it matched. Months passed without a break in the case, and officers finally decided to exhume Cole's body to take prints.

Grafft found himself trying to defend this to the local paper.

"In any homicide investigation there are things in the beginning that change later on," he told the St. Cloud Times. "Digging up a body is not uncommon."

Grafft told the paper, "We already have seven unsolved murders in this county. I don't want it to become eight. I've been living with the pressure of the other unsolved murders 24 hours a day since I took office. With this new murder, the pressure is even worse."

Despite all these unsolved cases, the sheriff rejected the idea that something was wrong with Stearns County in particular. "It's a pattern that's going on throughout the U.S.," he told a reporter in 1981. "You notice these because they are local. You don't hear about what happens in small towns near Cleveland, Ohio; or Seattle, Wash., or wherever. But these things are not isolated. Look at that young girl in St. Paul who was found in a dumpster. They don't have any leads on that one either."

Biggest unsolved case yet

Now the sheriff had another case to add to the list.

Grafft got to the dead-end road shortly after 10 p.m. on the night of Jacob Wetterling's abduction. He tried to reassure Jacob's parents, then he summoned volunteers from the fire department to search the woods next to the road with flashlights.

By the time the firefighters arrived, it was about 10:45 p.m. Jacob had been missing for about 90 minutes. The circle was expanding.

Ed Merkling, one of the firefighters who searched that night, said they walked in a straight line, one next to the other, about an arm's length apart. A sheriff's deputy with a shotgun went with them.

"They thought that the individual and Jacob were in this wooded area," Merkling said. "We were going to try to flush them out."

Grafft also called the state crime bureau and asked for a helicopter with a spotlight to search the area. The helicopter flew so low it almost clipped the power lines. After an hour and a half of searching, there was still no sign of Jacob or the abductor.

However, searchers on the ground did spot some shoeprints in the gravel driveway next to the abduction site. One of the prints looked like it came from an adult-sized shoe. The other print was smaller. They also found a set of tire tracks in the driveway near the prints. It wasn't clear whether the tracks had any connection to the crime. The boys hadn't seen a car, and it's not as though it's unusual to find tire tracks in a driveway.

But the way investigators looked at it, the only theory that made sense involved a car.

"It's not like you're in the inner city with apartment buildings and something where you can take someone and be gone in five blocks, and then have 5,000 places to hide," Mund, one of the detectives on the scene that night, told me. "How could you get away from there with someone and not have a car connected to it?"

And if a car was involved, the logical question would be: Did anyone see it on the dead-end road that night?

The neighbors

The long gravel driveway next to the spot where Jacob was abducted curves around and leads down to a farmhouse with a clothesline out front, a chicken coop and a grain silo.

Inside the farmhouse that night was a 33-year-old man named Dan Rassier. He was home alone.

Rassier was upstairs in his bedroom organizing his record collection when his dog Smokey started barking around 9 p.m.

He peered outside and saw a car coming down the driveway.

It was small and dark and the headlights were close together. Rassier didn't get a good look at the driver. He watched as the car turned around and headed back out toward the road. Then Rassier went to bed.

But a little later Smokey started barking again, and Rassier woke up. He looked outside and saw flashlights shining around his family's woodpile. He thought maybe somebody was trying to steal the firewood.

As he opened the front door, his heart started pounding. He realized that there was no way he could take on a bunch of guys in the dark by himself. So he ran back in the house and called 911.

The dispatcher told him that a child had been taken and that the men with flashlights were cops.

Rassier went outside, and as he walked up his driveway, he ran into Bechtold, the sheriff's deputy. They talked briefly. Rassier offered to search the farm buildings, but he didn't find anything.

No one paid any more attention to Rassier that night. No one knocked on his door. No one searched his house. Dan Rassier was just the neighbor.

For the next 27 years, investigators would claim that they knocked on every one of the doors on that dead-end road that night.

And it made sense. The neighborhood canvass is one of the most basic elements of crime solving.

Patrick Zirpoli, a former law enforcement officer who consults on child abduction cases across the country, told me that officers should know that they need to talk to the neighbors right away.

"You want to interview people multiple times," he said. "If a case drags on for more than a day and goes into the second and third day, you want to re-interview everyone again."

Vernon Geberth, a law enforcement trainer and former N.Y.P.D. lieutenant who has authored several popular textbooks for law enforcement, told me a neighborhood canvass is one of the most basic steps in a criminal investigation.

"I can tell you that every major case that I was in charge of in the city of New York that resulted in a successful conclusion was based on a good neighborhood canvass, where people were asked to report anything, even though they didn't think it was important," he said. "It turned out to be important."

Geberth didn't want to comment specifically on the Wetterling case because he hasn't seen the investigative file, but he told me it's hard to overstate how important it is to talk to the neighbors right away.

A lot of people don't realize they may have seen something significant, he said. It happens so often that there's even a term for these people: unknowing witnesses.

"Time's your biggest enemy in an investigation," Geberth said. "People have short memories. They don't remember everything correctly. You've got to get out there and talk to people and find out what the hell is going on."

I asked Geberth how long it's been a routine practice of law enforcement to canvass the neighborhood.

He laughed at the question. "Probably forever," he said. "Sherlock Holmes, OK?"

When I asked the initial investigators on the Wetterling case whether officers canvassed the neighborhood thoroughly that night, they all said the same thing: Yes.

"I would assume, yes. I mean, these detectives ask those questions," said retired FBI agent Al Garber, who worked the case in the early months.

"I think the neighborhood was looked at very quickly and very broadly," said FBI Special Agent in Charge Jeff Jamar.

"I'm sure I did," said Mund, the former Stearns County detective. "I'm just going through the logical steps of doing an investigation."

But no one I talked to remembered knocking on doors that night.

So we decided to check.

After a few dozen phone calls, a different picture emerged of what happened that night.

We tried to reach about 100 people who had lived on the dead-end road in 1989. Some of them had died. And of course, after 27 years, people's memories are going to be a little fuzzy.

We interviewed 26 people. Only two said they clearly remember being interviewed by law enforcement that night.

"We didn't hear anything," Marie Przybilla, one of the neighbors, said. "Isn't that weird?"

Some people remembered being interviewed days or weeks later. Others said they had never been questioned.

Jim Klein lived on the dead-end road in 1989, a bit closer to town. On the night of the abduction, he was in his garage working on a car, and he saw the boys returning from the store.

"I just happened to be walking outside right when they were going by," Klein said.

It was just minutes before Jacob was kidnapped.

Klein said he wasn't interviewed by law enforcement until about a week or two later.

Erica and Adam Sundquist don't remember talking to the police that night either. They lived just a few hundred feet from the abduction site. They were 12 and 9 at the time. On the night of the abduction, they saw Jacob, Trevor and Aaron pass on their bike ride home.

The two were outside throwing stalks of corn in the yard when they saw the boys come down the road, they told me. They remember the boys were going pretty slowly. They even threw some corn at them as a joke.

Shortly after the boys passed their house, Erica and Adam saw a burgundy car with a kind of jacked up back drive past, heading south on the road in the same direction as the boys.

They didn't think anything of it and went inside.

Jerry Klaphake, who also lived on the dead-end road, said his family woke up the next morning to find police cars and reporters swarming the neighborhood. No one had knocked on their door on the night of the abduction, he said.

He said there was something else that happened that first day that struck him as odd.

In the rush of people and traffic the day after the abduction, someone ran over the family's dog, and Klaphake wanted to bury it in his garden. But he worried that searchers would find the burial site and he'd look suspicious.

"It's a fresh grave, basically," he said.

Klaphake asked a neighbor to witness the burial, and he waited for someone to find it and question him. No one did.

"If they missed that, what else did they miss?" he said. "That's what I thought at the time."

Klaphake's son, Adam, was 14 at the time and was friends with Jacob Wetterling. People in the neighborhood even talked about how the boys looked alike.

If someone had talked to Adam that night, he could have told them a great deal.

About five or six years before Jacob was kidnapped, Adam Klaphake said, he was playing kickball in the yard with some friends around dusk.

One of the kids kicked the ball too hard and it landed in a ditch.

Adam ran across the street to pick it up. As he did, someone grabbed him from behind.

He couldn't get a good look at the person's face.

"They had me in a bear hug," he said. "The person had glasses, I remember that, and kind of a dark, raspy voice."

The man wouldn't let go.

Adam's sister opened the door and yelled for him to come inside.

"And the guy says to me, 'You're lucky your sister called you.'" Adam said.

Then the man threw him to the ground.

A few years passed. And then, in 1989, just a month or two before Jacob Wetterling was kidnapped, Adam and a friend were walking home from Tom Thumb, the same store where Jacob rented a movie the night he was kidnapped.

It was dark. Adam thinks it was after 10 p.m.

All of a sudden, a blue car came speeding toward them. It seemed like the driver was chasing them.

Adam and his friend jumped into the ditch, but the car was still right behind them, so they ran into a nearby garage.

The car followed them, pulled into the driveway and stopped. Then the driver turned on the brights.

"He just shined it on us," Adam said.

Adam said it felt like there were in a staring contest. The man's car was small and kind of boxy. Adam thought it looked like the kind of car a friend's mom had — a Pontiac 6000, or something similar.

When Jacob was kidnapped just a month or two later, Adam immediately thought of the strange man in the blue car.

But no one from law enforcement came to talk to them, Adam said, so he asked his dad to drive him to the command center a few days later.

Adam said he described the car to the Wetterling investigators and repeated the story in a separate interview with the FBI a few days later.

No one asked to speak with him again, he said.

Years passed, but Adam Klaphake couldn't get the story out of his head. Maybe the guy who chased him in the car was the same guy who had kidnapped Jacob. It certainly seemed similar. Same road. A couple of kids. In the dark. Adam even looked like Jacob.

In 2004 — 15 years after Jacob was kidnapped — Adam Klaphake took a day off work and went to talk to a detective at the Stearns County Sheriff's Office. He wanted to remind investigators about the man who chased him, but his memory had faded. He said he offered to take the detective on a drive through the neighborhood to show him where it happened. But he said the detective didn't seem interested.

"I remember leaving out of there just so angry because they weren't listening to anything I had to say," he said.

About a year ago, Adam Klaphake got curious and asked an officer if he could look at the statement he gave as a kid.

"When I got the transcripts, my jaw dropped," he said.

He and his friend had separately provided detailed, similar descriptions of the man and the car, he said. They both remembered the man had short hair and a stocky build. They both said they could identify him in a line-up.

"It totally slipped through the cracks," Adam said. "Now it's too late."

The circle expands

The search on the night of the abduction was a failure. No Jacob, no kidnapper, no clothing left behind, no car.

At 3 a.m., investigators made a big decision. They called off the search. Jacob had been missing for about six hours.

As the hours passed, the circle that had started out so small on the road where Jacob was taken expanded to include most of Minnesota and then most of the Midwest. As the days passed, it grew to include all of the Midwest, the United States, Canada, and finally, the world.

Investigators had missed their chance to find Jacob alive. It would take nearly 27 years to find his remains.

And yet, when I talked to the investigators who responded that first night, they all said they wouldn't change a thing about how they handled it.

"I don't know that there's anything we could have done differently," Mund, the former detective, said.

The next morning, the community of St. Joseph woke up to the news that Jacob was missing.

Even today, 27 years later, people in St. Joseph remember where they were when they found out. It's a moment no one can forget — central Minnesota's version of the Kennedy assassination.

Hope Klocker and her husband, Charlie, found out from the clock radio next to their bed.

"We sat up in bed and were like, 'Jacob?'" she said. "And of course then we raced, got dressed and got going right over to the Wetterlings."

Klocker owned Kay's Kitchen, the local diner. In those early days, it was packed with reporters, law enforcement, volunteers and people in town who wanted to swap rumors about the case.

Hundreds of people in St. Joseph started looking for Jacob on their own. They got in their cars and headed out to the back roads. They looked in ditches, old barns, woods and fields.

"We all wanted to get him home," Klocker said. "It was just crazy to think that he wasn't with us. He had to be found, and we were going to find him."

People in St. Joseph made flyers with Jacob's photo and put them on telephone poles, shop windows, doors, and parked cars. Everywhere you went, you'd see people with white ribbons pinned to their shirts to symbolize hope for Jacob.

Five days after Jacob was kidnapped, at 7 a.m., radio stations across Minnesota played one of Jacob's favorite songs, Listen, by Red Grammer, along with a message for Jacob from his mom, Patty.

"I just want Jacob to know that this song is for him to hear," Patty said, crying. "The heartbeat of humanity is beating for him. I know it will give him strength. If there's an ounce of compassion in the man who's holding him, he will let him go safely. Listen, Jacob. Can you hear our prayers? We love you."

The following week, thousands of people formed a human chain down a main road, shivering in the cold and sobbing. The chain stretched for three miles. Two baseball players from the Minnesota Twins showed up, wearing blue warm-up jackets embroidered with Jacob's initials.

Dozens of law enforcement officers began arriving in town, too. Grafft had asked for help from nearly every agency he could think of.

By the end of the week, there were nearly 100 officers working the case. They included Stearns County Sheriff's deputies, FBI agents, state investigators, and local cops from across Minnesota. The governor even called out the National Guard.

Search crews flew helicopters over the town. Officers rode on horseback through fields. Employees from the state Department of Natural Resources drove A.T.V.s down dirt roads.

Thousands of volunteers fanned out, walking through fields and ditches, looking for any sign of the missing 11-year-old boy.

Within weeks, the search for Jacob Wetterling had become one of the largest searches for any single missing child in the history of the United States.

And yet, investigators still hadn't talked to everyone who lived on the dead-end road where Jacob was kidnapped.

Pleading for leads

In every major criminal investigation, law enforcement has to make a choice. Keep the case local or go big. Investigators in the Wetterling case decided to go big — and it cost them.

Right away, investigators turned to the public to ask for help. They gave interviews to reporters and asked people to call in with leads.

Grafft had a replica made of the red jacket that Jacob had worn that night. A lieutenant held it up to the T.V. cameras and told everyone to be on the lookout for it. The red jacket became the most recognizable sign of Jacob. It was what everyone was looking for.

It wasn't hard to get the media's attention. By the time Jacob was kidnapped, the United States was already a decade into a national hysteria over child abductions. Jacob's kidnapping — on a dead-end road in a small town in the Midwest — made parents panic. If Jacob could be kidnapped, the thinking went, no child was safe.

The Wetterlings hoped the publicity would lead to a break in the case, so they gave interviews almost every day.

"I wanted everybody in the world looking for Jacob," Patty, Jacob's mom, told me. "We did what we had to, what we felt we had to."

The surest sign that the Wetterling case had become a big story came three weeks after Jacob was abducted, when it attracted the attention of the 1980's clearinghouse for human tragedy — daytime talk show host Geraldo Rivera.

Geraldo's TV crew set up a satellite feed from the Wetterlings' basement. The show opened with a solemn Geraldo holding a microphone back in the studio.

"Every time it happens, it puts an entire community into a state of shock," he said. "It's like a giant punch in the gut. Because all we can do, all the police can do really, is to speculate as to the intentions of the kidnapper. And just the options are horrifying."

The cameras panned to Patty and Jerry Wetterling sitting next to Sheriff Grafft and Jeff Jamar, the FBI supervisor assigned to the case. On the wall behind them, there were big sheets of paper covered in handwritten messages of hope and concern.

Geraldo asked, "As the days, Patty, turn to weeks, is it something that causes you nightmares as you try to pursue a reason why? Why your boy? Why that night?"

"I can't answer those questions," Patty told him. "I choose not to think about all the horrible options you made mention of at the beginning. I just won't allow those into my mind. At this point, I just want to believe that he's fine and we're going to get him home. I don't have nightmares, no."

The show also featured a young, intense John Walsh, of America's Most Wanted, as a kind of straight-talking expert.

"I know what they're going through," said Walsh, whose son had been murdered by a stranger in 1981. "They're going through the nightmare of not knowing. They're going and hoping, that sometimes in a rare incidence a child has gotten back that's been gone for a long time, but all of the people that are sitting there today know the harsh reality that lots of kids that are taken, are not taken by some caring person and taken to Disneyland. They're taken by someone who is into sexually assaulting children and if you're lucky, you'll find the body in a field."

Patty stared at the ground, as though she was trying to redirect all of her anger away from Geraldo and John Walsh and onto a few inches of basement carpet.

"What can they — the Wetterlings — do?" Geraldo asked Walsh. "Are they in a sense powerless now to the whims, the whimsy, the awful capriciousness of this madman?"

"That would be my opinion," Walsh said.

The show closed with a song of hope for Jacob, written by a musician in Minnesota.

"To all our parents, to their children who are out there, our prayers to you," Geraldo said. "We love you. Come home soon."

When the cameras stopped, Patty Wetterling grabbed the mic off her shirt and threw it on the ground.

Patty had hoped the show would help find Jacob. Instead, she felt exploited.

"They used us," she told me. "We had this sensational kidnapping, and they used us."

Patty decided to write Geraldo a scathing letter. She wanted to ask him, "How could you do this to us?"

But her sister urged her to reconsider.

"My sister told me, 'You get more bees with honey. You might need him down the road.'"

The letter was never sent. Instead, Patty wrote him a thank you note.

The Geraldo interview and other media appearances were painful for the Wetterlings, but they did generate leads for law enforcement. Thousands of them.

Grafft set up a 24-hour call center just to keep up.

There were leads about strange men spotted in other states; leads about cars spotted weeks later in other parts of Minnesota, driving suspiciously slow or suspiciously fast; leads about boys who looked like Jacob and had been seen in malls or gas stations hundreds of miles away.

Soon, some of those leads started sprouting leads of their own.

Garber, the retired FBI agent who worked on the case back then, told me how it would work.

Investigators would get a tip about something, like a white van, and they'd publicize it. And then people started seeing white vans everywhere and would call them in. One tip about a white van would turn into hundreds of tips about other white vans. Officers would try to find those vans, too.

Grafft had never seen so many leads.

He told a TV reporter, "We've been running so many white cars down and red cars down and tan station wagons and vans and we've been just getting a tremendous amount of calls here on this particular case here that it's kind of mind boggling."

Tipsters also called the Wetterling's house, so Grafft gave the family a separate phone to record the calls onto cassette tapes.

When I visited the Wetterlings a few months ago, Patty and I found some of the tapes in two dusty boxes in a crawl space in their basement. Hundreds of calls had been recorded.

In one, at 4:58 a.m. on a Wednesday, a man called and said, "I work for a carnival. And we just did a show in Omaha, Nebraska, and I seen a picture of this kid called Jacob Wetterling. I have a feeling that he's working for a small outfit called Rainbow Amusements."

In another call, a few months after Jacob was kidnapped, a man said he saw a pale boy at a McDonald's in Maplewood, Minn.

"I presume the boy was trained," the caller said, "because he started alerting this man that I was staring at them, so I tried to be nonchalant and go up and order something, so I could get a hold of the manager and have him call the police. And I looked back and they were gone."

The calls kept coming.

"I want to ask you a question right quick," one man said to Patty. "Is there anybody in your family, either side, with their legs off?"

"Not that I know of," Patty told him.

"I see," the man said. "One of the men that got your son don't have no legs. I know what the man that abducted your son looks like and everything. I am sick to death of seeing what this man has done to this boy, the legless man. This boy was raped on the side of the school bus right there where you live."

Patty cut him off. "You can't tell me that information without telling me where Jacob is," she told him. "That doesn't help me to know."

"Yes, yes, I know, I've hurt you," the man said. "I don't want to do that ... But your boy's all right."

"Good," Patty said.

Sometimes, people called pretending to have Jacob — or even pretending to be Jacob.

"The phone, it's a gift and a nightmare," Patty told me. "You can't not answer the phone. And that's a killer."

And then there were the psychics.

"Everybody keeps asking me, did you ever think of contacting a psychic?" Patty told me. "It's like, you don't have to. They come out of the woodwork."

Psychics, it turns out, love these kinds of cases. And in the early months of the investigation, they created some trouble in the Wetterling family.

When Jacob first went missing, the Wetterlings were a united team — Patty and Jerry. But as the investigation dragged on, Patty and Jerry started to go their separate ways a bit as they each tried to make sense of what had happened.

The pain of this was still close to the surface when I talked with them about it a few months ago.

"I was just all about talking to cops and the investigation, give me facts. I can deal with facts. That was my life," Patty told me. "Jerry, meanwhile, had all these spiritual connections and psychics."

Jerry interrupted. "That wasn't till a month after I started doing that," he said. "After he wasn't home, it was like, whatever, you know. If straight law enforcement isn't solving it, maybe there's another method out there. So then I went down that road for a couple years of craziness."

Patty jumped in. "It's crazy. He'd call it abductor hunting. They'd tell him to go out on a county road and say something and turn around three times. He'd do it. You do anything, but meanwhile I'm alone 'cause he's out abductor-hunting with these crazy people."

One psychic called so many times that Patty gave her a nickname — Midnight Margie.

"She'd call and they'd talk all night long," Patty said, "And she was just — "

"You're exaggerating," Jerry said. "We didn't talk all night long. There was always people around here. There was craziness, the investigation, and around eleven o'clock at night, things would kind of get a little quiet, and I would talk with her about psychic stuff, leads, but it wasn't all night long, but anyway."

"They all wanted some of Jacob's clothing," Patty said. "They wanted a toy. They wanted something. And I watched and Jerry would package up his stuff and send it off. It was a desperation. How could you not do everything, but it was so painful."

All these leads — from people claiming to be psychics, people with weird dreams, people claiming to be Jacob — went into the pile with everything else at the command center.

Most of the front-line investigators I talked to who worked on the case back then didn't question the way the leads were handled.

But then I talked to a retired state crime bureau agent named Dennis Sigafoos, who had joined the Wetterling investigation about a week after the kidnapping.

Sigafoos had more than a decade of experience investigating major crimes. He told me when he got to the command center, the phone was ringing nonstop. Hundreds of people were calling in with leads. Sigafoos was told to chase down a lead about a white van with Montana license plates.

Sigafoos was surprised. It was still early in the investigation, and already officers were being asked to pursue leads far away from the crime scene.

"We're focusing on things hundreds of miles away at times," he said. "Nobody (was) even looking at the neighborhood, from what I saw."

He said, "It appeared to me that because of the volume of the news and the leads coming in, that the case was lost right there."

Sigafoos said he argued with the lead investigators and asked them to allow him and a few other detectives to work the case starting from the basics, instead of having to deal with all the random tips. The lead investigators refused, he said.

He now regrets not pushing back harder. "I don't care if it would have thrown me out of that task force," he said. "I wish the hell I'd said more, and I wish I'd been thrown off."

Despite Sigafoos' complaints, the lead investigators on the case took these leads seriously — even the psychic ones. Retired FBI agent Garber told me it wasn't because he necessarily believed in psychics.

"I thought maybe there were times when a person might claim to be a psychic because they didn't want us to know the source of their information," Garber said. "So when psychic information came in, we looked into it carefully."

Every time law enforcement decided to chase down a psychic lead, it took officers and resources away from other parts of the investigation.

About a month after Jacob was kidnapped, investigators spent two days searching a 25-mile stretch of road near Mason City, Iowa — prompted by a lead from a psychic in New York. The search involved the FBI, the Iowa State Patrol, local officers and deputies from several sheriff's offices.

They didn't find anything.

While investigators were chasing down this psychic lead in Iowa, they still hadn't talked to everyone who lived on the dead-end road where Jacob was abducted.

By August 2016, there were at least 70,000 leads, according to the sheriff's office.

"I got a report last year that Jacob was riding on an elephant in a parade in Philadelphia," Bechtold, the investigator, told me a few weeks before the case was solved.

Bechtold had worked the case for nearly 27 years. He was the first officer on the scene that night and was later promoted to run the investigation. I wanted to know whether he thought it had been a mistake to ask for all these leads.

"Perhaps it did go too big, too fast instead of staying close in," he said. "If you spend so much time on leads that go nowhere, it may be taking from the lead that might take you somewhere."

But Bechtold couldn't let go of the idea that one of these leads, even one of the more bizarre leads, could help solve the case. He said they had no choice but to check them out.

Almost every law enforcement officer I talked to who worked on the case said something similar to this: There's no such thing as too many leads. Information is always good.

For nearly 27 years, investigators said, they reviewed every single one of these leads. They kept expanding the investigation more and more, asking people all across the United States for help.

But somehow, in all that noise, law enforcement failed to see what was right in front of them.

Heinrich's night

On the night of October 22, 1989, a 26-year-old man named Danny Heinrich got into his car — a dark blue 1982 Ford EXP — and drove to the town of St. Joseph, where the Wetterlings lived. Heinrich lived about a half hour away in the small town of Paynesville.

Inside Heinrich's car was a scanner he used to pick up police dispatch and a .38 revolver.

Heinrich wore camouflage pants, black boots and a dark jacket. He was about 5 foot 5 and stocky, with short dark brown hair.

Sometime after 8 p.m., Heinrich later told a judge, he turned onto the dead-end road that led to the Wetterlings' house. He saw three kids biking up toward town. He parked his blue Ford on a long gravel driveway. And then, he waited.

When the boys biked back, Heinrich got out of his car, put on a dark mask, and walked onto the road. He ordered the boys into the ditch and grabbed Jacob.

Heinrich took Jacob back to his car, handcuffed him and put him in the front passenger seat. Heinrich would later say that Jacob asked him a question. "What did I do wrong?"

Heinrich drove around for a while — long enough that he started to hear police activity on his scanner.

He told Jacob to lean forward in the seat and duck down, so no one would see him. Once they made it out of the town of St. Joseph, Heinrich told Jacob he could sit back up.

Heinrich kept driving around Stearns County. Eventually, he brought Jacob to Paynesville, where Heinrich lived, about 25 miles from the kidnapping. Heinrich pulled off on a side road near a gravel pit. He opened the car door for Jacob and took off his handcuffs. Then he walked Jacob over to a row of trees. He told Jacob to take off his clothes. Heinrich also undressed. He touched Jacob and had Jacob touch him. Then he told Jacob to masturbate in front of him.

The sexual assault went on for about 20 minutes, and then Jacob told Heinrich that he was cold. So Heinrich told him he could get dressed.

Jacob asked Heinrich to take him home, and Heinrich said he couldn't. Jacob started to cry.

Heinrich later claimed he saw a patrol car come down the road without its siren on. Heinrich said he panicked, took out his gun and shot Jacob. Then Heinrich left Jacob's body, got into his car and drove home.

Heinrich stayed at his apartment for a couple hours. Then he grabbed a shovel and walked about a mile back to the spot where he'd left Jacob.

Heinrich tried to dig a hole, but his shovel was too small. So he walked to a nearby construction site and stole a Bobcat. He started it up, turned the lights on and drove it back to the site. By then it was sometime after midnight — at least three hours after Jacob had been kidnapped.

Heinrich used the Bobcat to dig a hole and he put Jacob's body in it and filled it in. Then Heinrich returned the Bobcat and walked back to the spot. He tried to cover it up a bit more with grass and brush.

But Heinrich had forgotten to bury Jacob's shoes, so he walked a few minutes down the road and threw them in a ravine.

And then, Heinrich walked home.

It had not been a perfect crime. It involved hours of driving, walking down a highway with a shovel in the middle of the night, stealing a Bobcat, and leaving a body outside for hours.

And the criminal was no stranger to the Stearns County Sheriff's Office. Heinrich had been investigated by detectives earlier that same year — because Jacob wasn't the first boy Heinrich had kidnapped.

The one who got away

Earlier this year, I went out to meet with a 40-year-old man named Jared Scheierl at his home in Stearns County.

Scheierl's home is peaceful and quiet. It sits on 80 acres of woods along the Crow River. He lives there with his big, friendly black dog, Bear.

I came to talk to Scheierl because what had happened to him when he was a kid was perhaps the single best clue that law enforcement had in the Wetterling case.

Jared grew up in the small town of Cold Spring, just 10 miles southwest of St. Joseph, where the Wetterlings lived.

On the night of Jan. 13, 1989, about nine months before Jacob Wetterling was kidnapped, Jared, who was 12 at the time, went ice skating with a bunch of friends.

When they finished skating, the kids went to the Side Cafe to get chocolate malts. Most of the kids got rides home from their parents, but Jared and his best friend, Cory Eskelson, walked home.

It was around 9 p.m. The boys lived in opposite directions, so once they got to the end of an alley behind the cafe, they needed to split up.

But it was dark, so Jared asked Cory for a favor.

"Jared asked me to walk him home," Cory Eskelson said years later. "And I said no."

Jared was on his own. And as he walked, a man in blue car pulled up alongside him.

The man stopped and asked Jared for directions. Then he got out of the car, rushed toward Jared, and grabbed him by the shoulders.

"Get the f--- in the car," the man said. "I have a gun, and I'm not afraid to use it."

The man told Jared to lie down in the back seat and pull his hat over his eyes. He started driving. There was a walkie-talkie type scanner in the car. Jared thought he heard local law enforcement dispatch come across it. At some point, the man shut it off.

The man drove for maybe 10 or 15 minutes. Jared tried to keep track of where they were going by counting left and right turns. He paid attention to when the car crossed over train tracks.

Then the man turned onto a gravel road and stopped. It was dark, but Jared thought he could make out the lights of a nearby town in the distance.

The man climbed into the back seat and sexually assaulted Jared. When it was over, he kept Jared's jeans and underwear. He gave him his snowsuit back.

Then the man drove Jared back to town and dropped him off about two miles from Jared's house. He told Jared to run and not look back or he'd shoot. And he said something else that would stick with Jared for a long time.

"If they come close to finding out who I am, I'll find you and kill you," the man said.

Jared didn't go to school the next day, and his best friend Cory didn't know why.

Cory told me recently some FBI agents came to his classroom and asked him for his hat. They didn't explain why they wanted it, he said. "I thought they were maybe going to make hats or something."

Later, Cory learned that Jared had told the investigators the kidnapper wore a hat, and that it looked like his friend Cory's Cold Spring hockey hat.

Cory said the FBI didn't ask him anything.

"Nobody's ever asked me a single question about this other than you guys," he told me. "I've never been interviewed by police. I've never been talked to by any law enforcement ever. Not one person."

Investigators from the Stearns County Sheriff's Office did try to find the man who had assaulted Jared. Law enforcement records show that Jared described the man as short — maybe 5 feet 6 inches, 5 feet 7 inches — and about 170 pounds. He wore black Army boots, camouflage fatigues and a military-style watch. His voice was deep and raspy. He drove a dark-blue car.

Officers wanted to know where the man had taken Jared, so they had Jared lie down in the back seat of a squad car with his eyes covered.

Jared tried to retrace the route the man drove that night.

They ended up at a spot right off Highway 23, in between Cold Spring, where Jared lived, and a small town called Paynesville.

Three days after Jared was assaulted, a deputy from the Stearns County Sheriff's Office came up with a suspect — a man from Paynesville named Danny Heinrich.

At the time, Heinrich was 25. He was about 5 feet 5 inches and stocky. He drove a blue car.

Investigators put together a photo line-up of Heinrich and five other men. Jared picked out two people he thought somewhat resembled his abductor. One of them was Heinrich.

The following day, two detectives from the sheriff's office found Heinrich's car parked outside a plastics company where he worked. Jared had described the car as having a luggage rack and a blue interior. But when the officers went over to look, they noticed that Heinrich's car did not have a luggage rack and the inside was a grayish color.

Prosecutors didn't charge Heinrich or anyone else with kidnapping Jared. The crime was still unsolved nine months later — when a strange man with a raspy voice kidnapped Jacob Wetterling from the side of a road just a few towns over, in the same county.

Heinrich's life

Heinrich grew up in the town of Paynesville. He had two brothers, David and Tommy. His parents divorced when he was 15.

As a kid, Heinrich got into trouble a lot. He broke into garages and houses and stole radios, bikes, a tackle box and tools. He pried emblems off cars. On New Year's Eve 1979, he went to the King-Koin laundromat with a friend, smashed a vending machine and stole 55 packs of cigarettes, 30 candy bars, and 10 bags of M&M's.

Eventually, Heinrich got caught and confessed, and in 1980, a judge removed him from his parents' custody. Heinrich became a ward of Stearns County Social Services and was ordered to an adolescent treatment facility in Willmar, Minn.

"It is the Court's belief that Danny is in need of emotional help, which he is not receiving at home," Stearns County Judge Willard Lorette wrote in his March 25, 1980 order. "He is presently having problems at school. Danny has difficulty accepting authority and social relationships. It is felt that an out-of-home placement is necessary. Danny is in need of a setting where he will be treated for his emotional problems."

Roger Fyle, a friend throughout Heinrich's childhood, remembers him as a nervous and shaky kid.

"He'd think about something for a long time before doing it," Fyle said. "'Should I ride my bike or should I walk?' Just simple things, just simple things in life, he had trouble with."

Growing up, Roger and Heinrich ran around town together at night. "We were jolly little boys," Fyle said. Heinrich, he said, "was a little Curious George." They went around at night, looking in girls' windows, Fyle said.

Today, Fyle says even though he knows that Heinrich is a rapist and child murderer, he still looks back fondly on their childhood together.

"I do cherish the times that we did have," Fyle said, "because we had a lot of fun, you know, a lot of laughs. We laughed a lot together. But I don't want to know him, if he's f---ing kids, you know. That's sick."

Another person who knew Heinrich then was a man named Duane Hart, who now lives at a treatment facility for sex offenders in Moose Lake, Minn. He didn't respond to my request for an interview.

Hart was 16 years older than Heinrich, and he hung out with Danny's older brother, David.

The people I talked to who knew Hart then described him as a psychopath. They said Hart would talk about setting people on fire and tying people up without using rope.

"He told me that he could tie me to a tree and he could show me how to do it," Fyle said. "When he came around, there was something that came with him. There was a darkness that came with him."

Hart would buy alcohol for some of the boys in town, including Heinrich. Hart always seemed to have a group of boys around him.

At some point, Hart had sex with Heinrich, according to a private investigator who interviewed Hart in 1990. It's not clear whether Heinrich was a minor at the time.

In 1990, Hart was criminally charged with sexual assault, and he pleaded guilty to sexually assaulting four boys. Heinrich was not among them. Hart has been locked up ever since.

One part of Hart's story in particular got my attention. Several people told me that Hart had a favorite spot where he'd take boys to get them drunk and sexually assault them. It was out by a field near a gravel pit, just outside of downtown Paynesville, right off the main road into town. Fyle said Heinrich's older brother might have taken Danny there to party.

The boys had a name for this place. They called it the Big Valley.

The Big Valley would become an important clue in the Wetterling case, but it's unclear if law enforcement knew about it. Those who agreed to talk about Heinrich's early years said that they'd never been contacted by investigators.

Attacks on Paynesville boys

Heinrich dropped out of high school in 10th grade and later joined the National Guard.

Meanwhile, his run-ins with the law continued. In 1984, he broke into a consignment store across the street from his mom's apartment. A police officer found Heinrich hiding behind some boxes. Heinrich told the officer, "I don't know what got into me. I don't why I do these things." He ended up confessing to another burglary in town that same night.

Heinrich had a few DWIs, too. At one stop, in 1986, a Paynesville police officer noticed Heinrich had a police scanner in his car that he was using to monitor Stearns County Sheriff's Office radio transmissions. The officer confiscated it.

Paynesville police knew Heinrich as a juvenile delinquent, a petty thief and a drunk, and so when they began to get reports in the mid-1980s of a strange man grabbing boys off their bikes in downtown Paynesville late at night and trying to sexually assault them, it's not clear whether they suspected Heinrich right away.

Many of the assaults happened within a few blocks of the Plaza Hotel, a rundown apartment building where Heinrich lived with his mom.

Kris Bertelsen was one of those boys who was attacked. He was 12 or 13 at the time. He told me it happened one night when he and a friend were biking home.

"We went around a corner by some people's houses," he said. "They had a thick row of spruce. We came around the corner, and out of nowhere, from behind those trees, the attacker came running out and clotheslined my friend from his bike."

The man wore a long-billed hat, Bertelsen said. "He was all dark, combat fatigue-looking clothes, real dark clothing, like this was a mission."

Many of the police reports about these incidents were destroyed years ago, but from the ones that remain and my interviews with investigators and men in Paynesville, it's clear the attacks were similar. A short and stocky man, sometimes wearing a mask, would jump out of the dark and try to grab a boy and grope him. Some of the boys were riding their bikes. Others were just walking. One of the boys was attacked on his paper route. Most of the attacks happened at night. One boy said the man's voice was low and static filled. Another said it was a deep whisper.

Several of the boys said the man asked them their ages or what grade they were in. Sometimes the man would issue a warning: Don't move or I'll shoot.

The boys felt like they were being hunted. Some of them started carrying knives.

"We were all afraid, like, who's next?" Bertelsen said. "It was pretty systematic. It was a group of us who hung out together, hung around downtown. To be marked like that is terrifying. We had a feeling like we've (got to) take care of each other, watch out for each other.

The police in Paynesville tried their best to solve the assaults. The local paper, The Paynesville Press, published front page stories about the crimes. Sgt. Bill Drager described the crimes to a reporter. "After this guy grabs the boys, he tells them, 'Don't turn around or I'll blow your head off,'" he said.

Police even considered imposing a curfew, but they decided to just keep warning parents and kids: If a strange man approaches you, scream and run away as fast you can.

The attacks in Paynesville were never solved.

'It was the same demeanor'

Jared Scheierl's family didn't see the articles in the Paynesville paper. They didn't know about the other boys. Jared thought he was the only one. He started having dreams of a big black dog chasing him, and he'd wake up panicked and sweating. He slept on the floor of his parents' bedroom every night.

And then, in October of 1989, Jared heard about Jacob Wetterling's abduction just 10 miles away.

Like Jared, Jacob had been kidnapped on the side of a road while heading home in the dark by a short, stocky man with a gun.

"There were details that I recognized right away that indicated it was the same demeanor," Jared told me. "Some of the phrases were similar, description of the voice was similar."

The Jacob kidnapping seemed like almost a repeat of the Jared kidnapping, in which Heinrich was a suspect.

And investigators should have recognized it right away.

It's not just that Jacob's abduction seemed similar to another crime. It's that this kind of crime — the kidnapping of a child by a stranger — is among the rarest of all crimes. It almost never happens. And yet, here in this one county in central Minnesota, it had happened twice in one year.

Doug Pearce, one of the detectives on the scene the night of the Wetterling kidnapping, had investigated Jared's case just months earlier. Pearce had talked to Jared, had shown Jared the line-up with Heinrich and had looked at Heinrich's car.

On the night of the Wetterling kidnapping, Pearce took statements from the two kids with Jacob that night — the statements that described the abductor and how it happened. I tried to talk to Pearce, but I wasn't able to reach him.

According to the documents that have been released and the best recollections of law enforcement in interviews, no one went to look for Heinrich in those first few critical hours after Jacob was kidnapped.

But in the weeks after Jacob was kidnapped, investigators began to take a close look at Jared's kidnapping. They talked to Jared over and over again. They pulled him out of class at school a number of times.

"The kids in the class were taking notice of me coming in and out of class," Jared said. "And although we were protecting my identity, the word was getting around within Cold Spring that I was that boy."

Jared said investigators told him he was their best shot at finding Jacob, because the man who took Jacob was the same man who took him. So they kept pressing Jared to remember more.

After several interviews, investigators tried again. They brought Jared into a room and didn't let his parents come in, Jared said. And then they interrogated him in a more aggressive way than Jared had ever experienced before.

"You know who this person is," they told Jared.

Jared kept telling them no, he didn't. "As much as I wanted to provide the answer, I didn't know the answer," he said.

"I finally broke down in tears and came out of the room. My parents had seen me and said, 'We're done.'"

After that interview, Jared's family moved out of town. They wanted to get away from all the stress and questioning about Jared's assault, so they moved to a town they thought was more peaceful. They chose Paynesville, the town where Heinrich lived.

Bringing Heinrich in