Some prisons trying to maintain college education

It's one of the best defenses against recidivism, but investment is lacking.

More than 2 million people are in prison or jail in the United States. Almost every one of them will come out. So when prison populations boom, so do the eventual populations of former prisoners.

"We have that naive perception, OK, we solved this crime, we caught this guy, we sent him to prison, we can forget it," said John Linton, the former director of correctional education programs at the U.S. Department of Education. "But those individuals do come back into our community. It's a question of what kind of condition do they come back in?"

It's also a question of whether they are able to stay out of prison. Education is one of the best and most cost-effective means of achieving that goal.

At one time, thousands of prison inmates were attending college. About 350 college degree programs operated in prisons. But in 1994, Congress stripped Pell Grant eligibility from prisoners. Colleges and universities pulled out of prisons. By 2005, just 12 prisons had college programs.

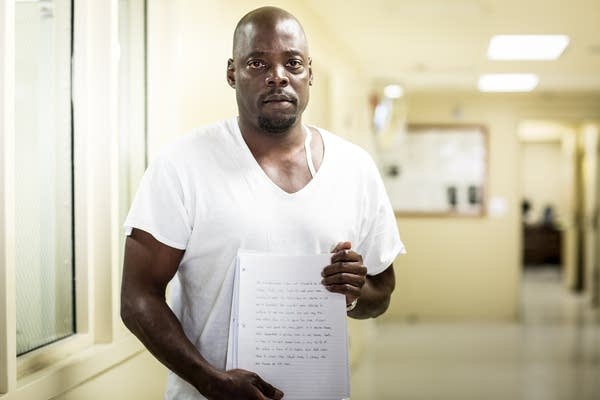

"Literally one day, the college programs, they came and packed up the crates with books, unplugged the computers and walked out of the prison," said Sean Pica, a former inmate in New York. "And it was gone."

In this documentary, originally released in September 2016, producer Samara Freemark looks at why the nation isn't investing in prison education anymore — and what it means for society at large when inmates without access to education are released.

Educate is a collaboration with The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization that focuses on inequality and innovation in education.

Educate is a collaboration with The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization that focuses on inequality and innovation in education.