The Tardy Furniture store murders: What happened that morning in July '96?

In the hours after the shootings, investigators were under tremendous pressure to solve the crime. But they had little evidence to go on.

When Sam Jones arrived at Tardy Furniture that morning, nothing looked out of place.

Jones had worked at the store in Winona, Mississippi, for 50 years before he'd retired. Earlier that morning, the owner, Bertha Tardy, had called to ask if he would come in to train two new delivery guys. So Jones drove downtown and parked in front of Tardy's about 10 a.m.

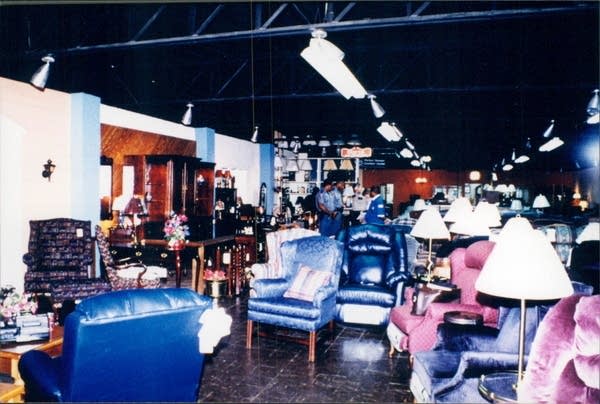

From the outside, the store looked like it always did. It was the last in a row of shops along Winona's historic Front Street. Tom Tardy had opened the store during World War II, back when downtown still buzzed with shoppers. Bertha had been his longtime in-store decorator. In 1985, Tom Tardy sold the business to Bertha, and in 1994, they married. By then, downtown Winona had declined, and many shops along Front Street were vacant. But not Tardy Furniture. The showroom was still stocked, and looking through its big glass display windows, it was easy for passersby to imagine how a country home could be spiffed up with a new bedroom or dining set.

When Sam Jones opened the front door that morning, July 16, 1996, he expected to see Mrs. Tardy and the new employees. But he didn't see anyone. He walked 20 feet or so into the cluttered showroom, past a cluster of armchairs and floor lamps. Nothing seemed amiss. But then he heard a strange sound.

"This noise [was] like somebody trying to catch their breath," Jones later testified. "I walked on a little further, and I heard it again. I looked down, and I saw what it was."

It was 16-year-old Derrick "Bobo" Stewart, one of the new delivery guys, lying in a pool of blood.

Then Jones noticed Robert Golden, 42, slumped against a counter beside Bobo. And Carmen Rigby, 45, face-down in front of a plaid sofa. Her car keys were wrapped around her pinky finger. Jones could see that 59-year-old Bertha Tardy was lying near the back office, the soles of her shoes pointing toward him. "After I figured I wasn't dreaming, well, I ran to get help for Bobo," Jones would later testify.

He hurried to a store up the street and told the woman working there to dial 9-1-1. The call came into police dispatch at 10:21 a.m. Denise Carver answered it. The woman on the other end of the line didn't exactly know what was going on but said a man had come to her store to say that several people were lying on the floor at Tardy's. To Carver, it sounded like they'd fainted from the July heat.

Winona Police Chief Johnny Hargrove was patrolling a few short blocks away, and he raced to Tardy's in less than a minute.

Hargrove didn't see Sam Jones, who was still up the street. Entering the store, the first thing he noticed was Bertha Tardy's body. Though she was farthest from the storefront, she was lying in an aisle that ran the full length of the showroom. As he approached her, Hargrove glanced to his right and saw the other victims lying near the decorating center, a white counter that sat like an island in the middle of the store. Then he heard Bobo gurgling.

Hargrove realized he didn't have his portable radio. He drew his gun and slowly backed out to the street. At his patrol car, he called for backup, an ambulance, a coroner and the district attorney.

Officer Kenny Townsend arrived soon after. Right away he saw that Hargrove, an ex-army sergeant, looked flustered. Hargrove told him to go inside to look for 76-year-old Tom Tardy. Though Tardy had turned over his business to Bertha, he still spent most mornings in the store. Hargrove thought he might be dead, too.

"Draw your weapon," Hargrove said. "It's the real shit."

The officers didn't know if the killer was still inside. With gun in hand, Townsend moved quickly through the store. There was no sign of Tom Tardy or anyone else.

After that, things happened fast. Paramedics arrived, hoisted Bobo Stewart onto a stretcher and rushed him to a nearby hospital. Law enforcement taped off the scene to keep the gathering crowd at a distance, but they didn't exactly restrict access. Various officials came and went — including the mayor, and even Barney Morgan, the town's animal control officer. "I had a uniform on. I had a badge, so I was allowed to go in," he would later say.

Before long, two investigators with the State Highway Patrol and one from the district attorney's office — the men who would take control of the case — set up a command post at a dining table inside the store. There, they began interviewing witnesses.

The most detailed notes of the evidence collected that day were written by Melissa Schoene and Jodee Creel of the Mississippi state crime lab. They traveled up to Winona from Jackson, 90 miles away, and arrived at Tardy Furniture just after 1 p.m.

Schoene recovered two bullets, two bullet fragments and one live round on the floor near a bookcase. She also collected five .380-caliber shell casings. Four people had been shot with only five bullets. Each victim had been shot in the head.

One of the first pieces of evidence in the case had been spotted by Hargrove, who had noticed several faint footprints in the blood near where Bobo's baseball cap was found. In documenting the scene, Schoene sketched the zig-zag pattern of the three shoeprints visible on the brown tiled floor. She inspected the shoes of Sam Jones, the man who'd discovered the bodies, and drew a picture of his treads. It was clear the footprints hadn't been made by him.

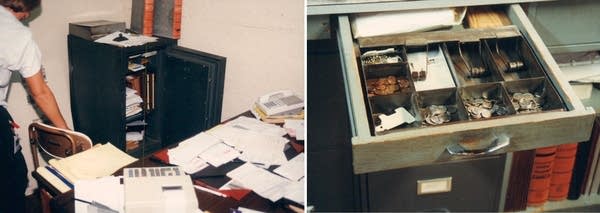

Creel inventoried the money drawer in the cash register: no bills, a variety of coins, several sets of keys. Schoene dusted the counter for fingerprints.

In the back office, Schoene noted, Bertha Tardy's paperwork was neatly piled, her pen top was off and her purse was sitting on a chair untouched. The door to the floor safe was, Schoene wrote, "closed but not locked — contents of safe are neat and in order (does not appear to have been gone through)."

In the afternoon, hundreds of Winona residents gathered on a grassy slope across the street from Tardy Furniture, even as a heavy rain began to fall. They prayed and cried and watched as the bodies of Robert Golden, Carmen Rigby and Bertha Tardy were removed from the scene. Dispatcher Denise Carver went home and threw up. Officer Kenny Townsend filled out an incident report, which would later be lost.

As investigators tried to piece together what happened and who had done it, they had little evidence to go on. Though the murders had been committed right downtown in broad daylight, nobody had seen or heard a thing — not the owner of the dry cleaners next door or the mechanics in the body shop behind Tardy's. Fingerprint and DNA analysis wouldn't point to any suspects. Investigators had shoe prints, but no shoes, and bullets, but no gun.

There was no apparent motive, and the randomness of the crime made it terrifying. Residents worried that a murderer was on the loose, and they wanted him caught quickly. State Trooper Tommy Purnell remembered how stressed Chief Hargrove looked. "The pressure was on him pretty good," Purnell said. "He needed a lead right then to satisfy those people, and he didn't have one."

Late in the day, Hargrove issued a statement saying that four people had been questioned and released by law enforcement. It would be the beginning of a months-long investigation.

Winona Mayor Sonny Simmons told reporters that robbery didn't appear to be a motive, but he didn't offer much more than that. "Really, we don't have any clue as to what took place or why," Simmons told the Jackson Clarion-Ledger.

"Everybody's pretty well in shock," he said. "Things like this don't happen in places like Winona."