The case against Curtis Flowers relies on three threads of evidence: the route that witnesses say he walked the morning of the murders, the gun that prosecutors say he used to shoot four employees at Tardy Furniture, and the people he supposedly confessed to while in jail. In this episode, we investigate the alleged murder weapon and the strange history of the man who owned it.

May 8, 2018

In June 2010, David Balash took the stand in the courthouse in Winona, Mississippi. As a court-appointed forensics expert, Balash had been tasked with reviewing the ballistics evidence in the Curtis Flowers case.

From the start, investigators had faced a fundamental problem: They didn't have the murder weapon. They knew a .380-caliber handgun had been used to kill the four employees at Tardy Furniture in 1996, but the gun had never been found. How could they link a suspect with a gun they didn't have?

Ultimately, they uncovered two bullets they believed had been fired by the gun belonging to Doyle Simpson, who was Curtis Flowers' step-uncle. It's the gun prosecutors say Flowers stole the morning of the murders. Investigators dug those bullets out of a wooden post on the property of Simpson's mother and compared them to a bullet that they recovered from a mattress at the crime scene. The Mississippi Crime Lab in Jackson had matched the bullets. But prosecutors wanted another expert opinion. That's where Balash came in.

He first examined the evidence in 1998, after Flowers had been found guilty the first time. Balash, a retired Michigan state trooper who's a ballistics and explosives expert with decades of experience in the field, testified at the five subsequent trials that the gun Flowers allegedly stole was the murder weapon. This was a key piece of evidence linking Flowers to the crime. At Flowers' last trial, in June 2010, Balash was unequivocal that the bullets found at the crime scene matched Doyle's gun. "It has to be 100 percent or I will not offer that opinion," he testified.

But how could he be so sure?

On the day of the Tardy Furniture murders, Doyle Simpson got to work around 6:15 a.m. He parked his 1980 Pontiac Phoenix as he always did — right next to the door of the Angelica sewing factory, unlocked.

Doyle went about his ordinary custodial duties, collecting scraps of fabric and running them to the dumpster. Over the course of the morning, he went to his car several times — once to grab his breakfast from the front seat around 9:15 a.m. and again, shortly after 10 to roll a window down for ventilation, according to his testimony in court. He said he didn't notice anything out of the ordinary.

Around 10:45, Doyle collected several lunch orders from his coworkers and headed to his car once more. He testified that when he sat down in the driver's seat and pulled the car door shut, the glove box, which had been locked, suddenly popped open. He noticed that the gun he'd put inside just the evening before was gone.

Doyle ran to the factory behind Angelica, where his brother worked, and asked if he'd seen anything. He hadn't. Doyle told his supervisor that somebody had broken into his car and taken his gun. Then he drove to Fuzzy's Fried Chicken to pick up the lunches he'd been dispatched to buy. At Fuzzy's, Doyle mentioned the strange story of his missing gun to several other people. After that, he went back to work, but the news about his gun wound its way from Fuzzy's to the detectives investigating the Tardy murders downtown.

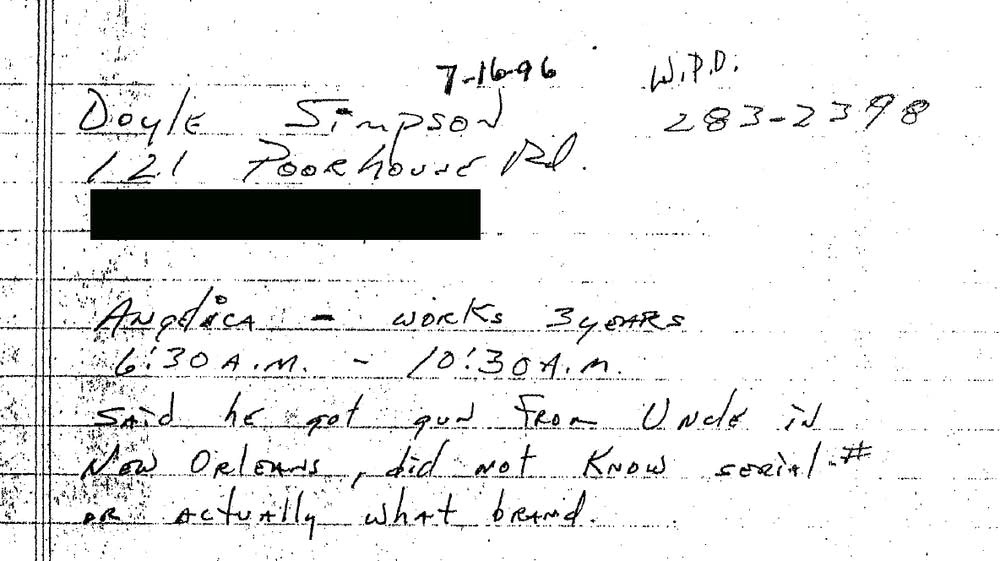

Doyle never called the police, but they caught up with him that afternoon. Below are the brief notes from that conversation. Doyle told investigators that he didn't know the gun's make or serial number and that he'd gotten it from an uncle in New Orleans.

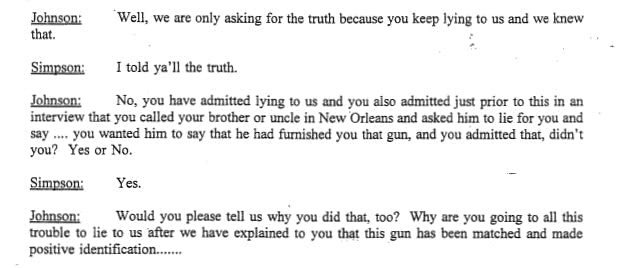

Doyle was lying about where he'd gotten the gun. It's unclear why. Police would later talk to the supposed uncle, Robert Campbell, who's actually Doyle's half-brother. He would tell them the truth. Several people knew Doyle had actually bought the gun from a Winona man named Ike Williams. In a statement to John Johnson, Ike confirmed he'd sold the .380 to Doyle.

On August 14, a month after the murders, John Johnson interviewed Doyle Simpson at the Winona Police Department. Doyle came clean about having purchased the gun from Ike, but Johnson grilled him about why he'd lied in the first place. Johnson then told Doyle that his gun had been identified as the murder weapon. Doyle was clearly surprised to hear this. He asked for confirmation. "Do y'all know that that is the same gun?" "Yes, we do," Johnson replied, "How do you answer that?"

"I don't have nothing to say," Doyle responded, bringing the interview to an abrupt end.

Doyle's next interaction with investigators came six days later, on August 20.

There's a note in the case file that documents a call from Doyle. He had a message to deliver to investigators, one that seemed to point suspicion away from him and to implicate his nephew instead.

"Curtis," the note read. "Acting funny."

When Curtis Flowers testified at his first trial, he said on the stand that he knew Doyle Simpson owned a gun. But he didn't know the gun was in the glove box of Simpson's car on the morning of the murders. For his part, Doyle Simpson has changed his story a few times on this point. He testified that Flowers knew the gun was in his car. But he also testified at various times in the six trials that he usually kept the gun in his mother's house, under his mattress or in his car. In the following exchange from the first trial, Simpson testifies under cross-examination from defense lawyer Billy Gilmore on Oct. 15, 1997, that Flowers had no way of knowing where the gun was on the morning of the murders. It's far from clear that on July 16, 1996, Flowers would have found the alleged murder weapon.

Simpson: That evening.

Gilmore: The evening of the 15th?

Simpson: Yes, sir. That evening.

Gilmore: Okay. But you left your car at your mother's house?

Simpson: Right.

Gilmore: And I believe you said it had been in the house for several days prior to that?

Simpson: A couple of days; that weekend.

Gilmore: Okay. And where had it been prior to then?

Simpson: Sir?

Gilmore: Where had it been prior to then?

Simpson: In my, in the house.

Gilmore: It had been in the house for how long?

Simpson: Because I had put it in there — where had it been when?

Gilmore: No.

Simpson: Say that again now.

Gilmore: You said you put it in your car on the evening of July the 15th of '96?

Simpson: That evening, yes, sir.

Gilmore: All right, how long had it been at your mother's house?

Simpson: Oh, it be there all the time.

...

Gilmore: Did you have any particular reason for putting it in the car that particular afternoon?

Simpson: Well, I was going to go up the road with it.

Gilmore: Going to go up the road with it?

Simpson: Yes, sir.

Gilmore: What do you mean by that?

Simpson: Going up the road, by David Weems.

Gilmore: By David Weems?

Simpson: Yes, sir.

Gilmore: Who is David Weems?

Simpson: That's my cousin.

Gilmore: Okay, what was you going up there for?

Simpson: We was going, he was going to clean it up for me.

...

Gilmore: Okay. So there is no way that Curtis Flowers would have known that gun was in that car that particular morning, was it?

Simpson: No, sir. Not as I know.

Gilmore: No further questions.

The police would later describe it as a tree, but it was really more of a swamp vine. Doyle Simpson was handcuffed to it, his feet sinking into the marshy sludge. Untold Louisiana swamp creatures — alligators, snakes, snapping turtles — lurked in the tangled thicket behind him.

Doyle had two holes in his back, near his shoulder blade, where the freckled man had shot him. The bullets had traveled upward through his body. One was lodged in the base of his skull, and the other had ripped through his throat, narrowly missing his carotid artery, and exited through the front of his neck. He couldn't scream, he couldn't even talk. Out there, no one would have heard him anyway.

It was December 15, 1986. A couple hours earlier, 29-year-old Doyle had pulled up in front of his cousin Clyde's house, a tan rambler in Kenner, Louisiana, a town on the outskirts of New Orleans. It was a Monday morning, around 11:15. Clyde's wife, Elaine, had also just arrived. She parked in the carport alongside her little home on the crowded street.

As Elaine prepared to walk in her side door, she heard two gunshots. She looked left and saw a man darting across her lawn, as if he'd just bolted out the front of her house, a blue steel gun in his hand.

Elaine saw the man run toward Doyle's yellow Ford Pinto, point the gun at Doyle and yell, "Drive!" Doyle's car sped off.

Then Elaine entered her house and found Clyde lying in a pool of blood on the kitchen floor. She ran back to her car and drove to a nearby donut shop to use a payphone to call police.

At 11:38, Kenner Police Detective Steve Caraway arrived at the scene. The door to the Simpson's house looked like it had been kicked in. Clyde's neck had been slashed, he'd been shot three times in the head and once in his stomach. Clyde Simpson was dead. Meanwhile, Doyle was trapped in a car with the murderer.

The man directed Doyle to steer his Pinto away from New Orleans and its suburbs. They crossed the Mississippi River and drove more than 25 miles, through the sugarcane fields and into the swampland of St. John the Baptist Parish. They turned onto a gravel service road. As they neared the edge of the swamp, Doyle's little car got stuck in the mud. They walked the rest of the way to the tree-like vine.

The freckled man stole Doyle's wallet, shot him twice and took off on foot. Doyle was alone, stuck to the tree and bleeding to death. It's not hard to imagine his despair: Doyle slumped over, his weight bearing down on the frail branch, his eyes scanning the tangled brush beneath him for something, anything, that might set him free.

Natalie Jablonski

Rehman Tungekar

Parker Yesko

Will Craft

Dave Mann

Andy Kruse

Catherine Winter

Chris Worthington

Gary Meister

Johnny Vince Evans

Corey Schreppel

Veronica Rodriguez