Why the eyewitness IDs of Curtis Flowers may not be reliable

Catherine Snow and Porky Collins picked Curtis Flowers out of photo lineups. But, according to two experts, the flawed procedures used by investigators make these identifications highly questionable.

A photo lineup is a classic investigative tool. For decades, police have presented crime witnesses with arrays of images known as "six-packs" and asked them to pick out the perpetrator they saw.

But it wasn't until 1999, as a growing body of social science on the nature of eyewitness memory was emerging, that the U.S. Department of Justice first issued guidelines about how photo lineups should be conducted. Before that, law enforcement officers used whichever technique seemed best to them, sometimes with tragic consequences.

Of the 358 people exonerated by DNA in the United States since 1989, nearly three-quarters were sent to prison at least in part by mistaken eyewitness identification. It is the leading cause of wrongful convictions, according to the Innocence Project.

In the Curtis Flowers case, two witnesses were shown photo lineups more than a month after the murders. One was Porky Collins, who said he saw two African-American men across the street from Tardy Furniture not long before the murders. The other was Catherine Snow, who said that, on the morning of the murders, she saw a man standing next to Doyle Simpson's car outside the Angelica garment factory, where she worked. This seemed significant because prosecutors believed that the murder weapon was stolen from Simpson's car.

Both Collins and Snow eventually picked Flowers out of photo lineups, with varying levels of certainty. But how reliable are their identifications?

We talked to two psychologists who are experts on eyewitness memory — Iowa State University's Dr. Gary Wells and Dr. John Wixted from the University of California, San Diego — about what makes for strong identifications. Then we graded the two photos lineups in the Flowers case against the five criteria the experts provided.

Quality of sighting

This is so obvious, it's easy to overlook. For a witness to reliably identify a suspect later on, he or she needs to have gotten a good look at the person in the first place.

In a notable 2011 ruling, the New Jersey Supreme Court identified a list of factors that can weaken the strength of an initial sighting: stress, intoxication, poor lighting, only a brief exposure to the suspect, a focus on a weapon in the suspect's hand, and "cross-racial" effects (studies have shown that witnesses are less discerning of detail when observing faces of people of a different race).

Also, people generally need a reason — like witnessing a crime in progress — to bother to create a memory of someone they see in public. "We encounter people all the time and have absolutely no memory of their faces," Wells said. "We are not videotapes making records of our world."

Did Catherine Snow and Porky Collins have the opportunity to make clean memory imprints?

Snow: Probably. She was in a familiar, low-stress environment when she saw the person standing near Doyle's car. The sun was up, she was standing still and relatively close to the person she observed. She and the person were both African-American.

Collins: No. He was driving when he saw the two black men standing near a car. He had no particular reason to notice them except that one made a gesture with his hand, and Porky thought they might be arguing. "I just for one split second, I got a glimpse," Porky told investigators. Then he circled back and got another quick look, but there were cars and a tree in the way. One man's back was toward him. "I never seen his face," Porky said. Porky was white and the men he observed were black, making it even less likely that he was able to form a distinct impression of their faces.

Detail in the initial witness statement

The best indication of whether a witness actually got a good look at a suspect is his or her first statement to police. The description provided should be detailed and specific. The ability to say the suspect had a pointy nose, for instance, or a goatee or a birthmark is evidence that the witness extracted meaningful descriptive information from that initial sighting.

If, on the other hand, the witness can describe the suspect in only broad terms like age, race and gender, then he or she only has what Wells calls "a gist memory." Gist memories are a bad baseline against which to compare photos. They're an indication, Wells says, "that there's no ground truth."

Did Catherine Snow and Porky Collins make more than just gist memories?

Snow: No. She said she saw a stocky black man, 25 to 30 years old, approximately 5-foot-10, with short hair. She said she could "possibly" identify him. "She knows the gist," Wells said. "That doesn't mean that she picked up on the details. And why would she have? She went out to her car. She came back in. This was a non-event."

Collins: No. His initial statement gives almost no description. He simply says that he saw two black men of medium complexion.

The composition of the photo lineup

A lineup is composed of a photo of the suspect and five "filler" images. If it's conducted properly, the fillers meet several critical imperatives:

They are all plausible choices given the witness' initial statement. A person who has read the witness' statement but didn't actually witness the crime should be able to fail the test.

There should be nothing suggestive about any of the photos — no one photo should jump out. "You don't want the suspect to stand out in any way," Wixted said. "The worst way the suspect can stand out is by matching the description better than anybody else."

The five filler photos cannot be of other suspects. They must be "known innocents." "If everybody's a suspect or everybody's potentially prosecutable, the test has little or no diagnostic value," Wells said. "If everybody's a suspect, hell, I could do that one. And I'm not a witness to anything."

Were the photo lineups presented to Catherine Snow and Porky Collins fairly composed?

Snow: Yes. To varying degrees, the men in her photo lineup all matched the original description Snow provided. The most glaring deficiency in the lineup is the photos are black and white. The lack of color means that some facial definition is lost, but it's not a deal-breaker. "The main thing is whatever flaw there is, if it's spread across all six faces, it doesn't selectively disadvantage any particular person," Wixted said. The social security numbers of the fillers are listed and none of them was an alternate suspect.

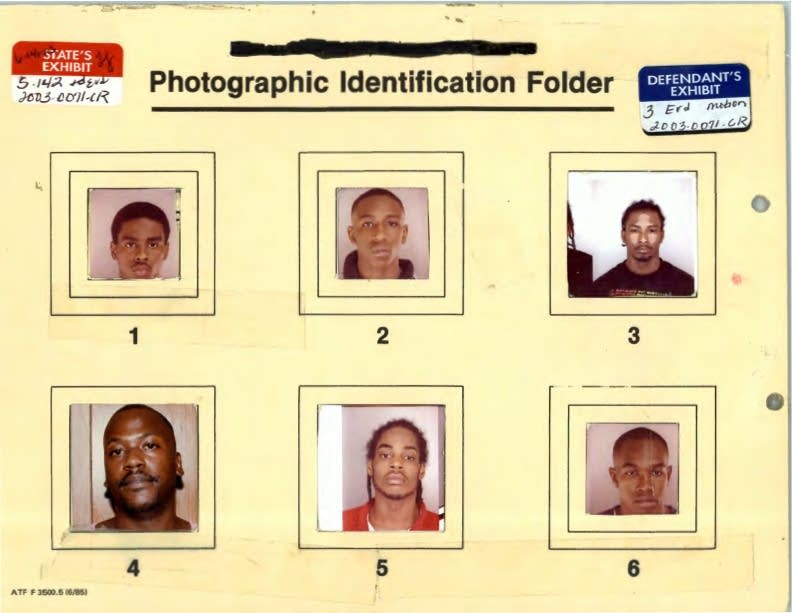

Collins: No. Porky's lineup had a number of problems. In the second panel (pictured on the right below), the six photos could not look more different. Three are small photos of teenagers. Two of the guys have braids. Four have facial hair. The man in photo 3 is bright and splotchy, the guy in photo 4 — Curtis Flowers — is bigger than the rest. In some cases, bigness could cause a selective bias toward the suspect, but in this case both Wells and Wixted believed that since each photo stood out in its own way, Flowers' size was a wash. Also, Porky only saw one man's face, but he's being shown photo lineups with at least two suspects — Doyle Simpson and Curtis Flowers. The men in the other 10 photos are not identified.

Witness interview process

The best practices here have changed a lot since 1996. Today, a scrupulous police interviewer will take pains to ensure that the witness doesn't feel pressure to pick a photo if he or she isn't certain. This is done by giving a clear set of instructions at the start, something like, "Keep in mind that the person you saw might not be in this set of photos at all. ... It's just as important to eliminate people from suspicion as it is to incriminate them."

Also, we are now well aware that coaching, suggestion and even non-verbal reactions by police officers can powerfully lead a witness. If detectives in the room hear the witness say something they're hoping for, they may nod their heads or lean in. Witnesses are attuned to this, even if only subconsciously; they trust law enforcement and want to help. Wells says the best way to ensure this doesn't happen is a double-blind presentation of the lineup. There should be only one person showing the photo array, someone who doesn't actually know who the suspect is. The officer should disclose this to the witness and instruct the witness not to look to him for coaching or cues.

Finally, this entire process must be documented, ideally as an audio or video recording. We should know the instructions given to the witness. We should hear the witness talk through his or her thought process. We should see how investigators are leading or not leading the witness along.

Were Catherine Snow and Porky Collins given clear instructions and not coached?

Snow: No. Even in 1996, documenting the process in some way — perhaps just a handwritten note — was typical. For Snow's lineup, we have nothing except a mention that there were three investigators in the room. We don't know what they said to her during the lineup. It's clear they had a tape recorder, but they didn't seem to turn it on until three minutes after the interview ended, at which point they took a brief statement. There's evidence in this statement that Snow is being coached. She says the man she saw was about 5-foot-6 and is corrected. "I think you have already given us the height of 5-foot-10," investigator John Johnson says. "Yes, sir," Snow replies.

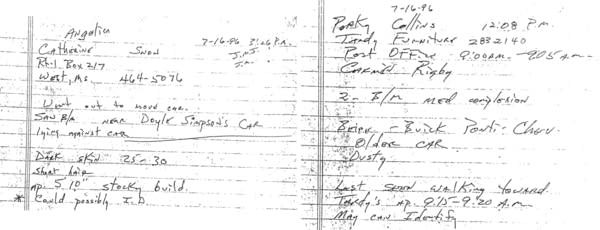

Collins: No. In some ways, Johnson's notes on Porky's lineups are better. They give an indication of how Porky moved through the photos. We can tell that Porky pointed to photos 1, 3 and 6 — Doyle Simpson — in the first panel. We can tell that he then pointed to photo 4 — Curtis — in the second panel. There are two big issues, though — the first is that we don't have any idea how Porky was instructed at the start. He'd told investigators that he saw two men but only one of their faces. Is he being shown all 12 of these pictures and being asked to pick out the one man whose face he saw? Or is he also supposed to pick out the man whose back he saw? The second issue is that Porky was given affirmation after he landed on Curtis Flowers. He pointed to the photo of Curtis and said "I believe it's him. It looks like him." John Johnson responded by asking Porky if he knew Curtis Flowers. There is no typed statement from Porky on the day of the lineup.

Witness certainty

In a review of 161 wrongful convictions based on eyewitness testimony, University of Virginia law professor Brandon Garrett found that most mistaken witness identifications had one thing in common: The witnesses expressed a lack of certainty about their selections at the start.

Testing memory contaminates memory. Over repeated exposures, a messy, ambivalent identification — what John Wixted calls inconclusive evidence — can be polished down into a sharp incriminating one. Witnesses can grow increasingly sure that their choice of the suspect was self-directed and that they were positive from the outset. But investigators shouldn't let this happen,according to Wixted. If the witness doesn't express high confidence at the start, investigators should cut him loose.

Wixted describes what a high-confidence identification looks like: "The witness will view the photo lineup and, in a matter of seconds, will point to the guy and say, 'that's him, I'll never forget that face, that's definitely him.' They'll sometimes show emotion if they were a victim. They might start crying. No hesitation, no uncertainty, no difficulty making the ID."

A low-confidence ID is one where the witness clearly has no initial strong impression and tries to work through the photos by process of elimination. Wixted saw one recently: "The guy looked at the photo lineup and 'hmm' was his first expression. And he sat there for like 60 seconds and started saying things like, 'Well, I can definitely rule out these two.' That's not how face recognition memory works. This guy analyzed for like 10 minutes, trying to decide about the hair on this guy, the hair on that guy. What you know already is that this guy does not recognize a face. But ultimately, he does land on the suspect."

Did Catherine Snow and Porky Collins make high-confidence IDs of Curtis Flowers?

Snow: Maybe. By the time investigators recorded a statement from Catherine Snow, she did sound certain. But we don't know what her first impressions were. There's also an odd fact about her identification. Snow would later admit that she actually knew Curtis Flowers. Known-person IDs tend to be very strong. Yet instead of telling police that Curtis was the person she'd seen outside the factory, she asked to pick him out of a photo lineup.

Collins: No. Porky's statements were filled with the hallmarks of a low-confidence ID. He pointed to all sorts of people who didn't look like one another. He mulled the details of their hairlines. He said he was "unable to be positive" on the first panel. On the second panel, his first reaction to Curtis was wishy-washy. "I think that's him. He was about my height," he said. "It looks like him." He moved closer to certainty after John Johnson reaffirmed his choice.

In total, Snow's witness ID of Flowers failed on two of Wells' and Wixted's five criteria for a reliable identification. And Collins' ID failed on all five counts.