Prosecutors have always said that Curtis Flowers was the only serious suspect in the Tardy Furniture investigation. But we found a document showing that another man, Willie James Hemphill, had also been questioned just days after the murders. Who was he? Why was he questioned? When we finally found Hemphill, living in Indianapolis, he had some very surprising things to say about the case.

June 26, 2018

By law, a criminal defendant must be given evidence that could point toward his innocence. It's possible prosecutors failed to do this in the Curtis Flowers case.

The idea that a defendant is legally entitled to this type of information comes from the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brady v. Maryland. John Leo Brady had been found guilty of murder in Maryland in 1958. He and an accomplice, Donald Boblit, had stolen another man's car and, in the course of the robbery, beaten the man to death.

Brady and Boblit were both convicted of murder, in separate trials, and sentenced to death. Later, it came out that Boblit had actually confessed to the killing and told police that he alone had perpetrated it. What's more, prosecutors knew about Boblit's statement when they put Brady on trial for the murder he hadn't committed and never revealed it to the defense.

Brady appealed his conviction, claiming his trial had been unfair. In 1963, the Supreme Court threw out his death sentence. "The suppression by the prosecution of evidence favorable to an accused," wrote Justice William Douglas in the majority opinion in the case, "violates due process where the evidence is material either to guilt or to punishment, irrespective of the good faith or bad faith of the prosecution."

The key words here are "favorable" and "material," meaning the withheld evidence must have been good for the defendant and likely to have made a difference at trial. Importantly, Brady holds that ignorance on the part of the prosecutor is no excuse. Police, sheriff's deputies, jailers and highway patrol investigators work for the state. If they turn up anything that casts doubt on the defendant's guilt, the prosecutor must hand it over to the defense.

Evidence that points to another suspect can be especially significant, said Bennett Gershman, a law professor at Pace University. "That a third party may have been involved in the killing, may have been the perpetrator, is certainly favorable evidence to the defendant," he said.

In the Curtis Flowers case, District Attorney Doug Evans and investigators have asserted that Flowers was the main suspect from the beginning.

In a hearing before Flowers' sixth trial, Judge Joseph Loper asked Doug Evans, "Has the state got any exculpatory evidence?" "No sir," Evans replied.

"Have you ever had any that has not been provided?" Loper followed up. "We have never had any evidence that showed anything other than this defendant's guilt," Evans said.

But a close look at the investigative file reveals traces of other suspects.

In October 2015, almost 20 years after the murders at Tardy Furniture, one of Curtis Flowers' lawyers was paging through his case file, when she saw a familiar face.

Katie Ali had been researching parallels between the Tardy Furniture murders and a string of similar crimes that had happened that same summer in neighboring Alabama. Both involved store employees who were shot execution-style, a .380 handgun that might have jammed, and a suspect wearing Fila shoes. Back in 1996, there had even been speculation in the media that the crimes could be connected, and investigators had told the local paper they were looking into it.

But there was no mention of the Alabama crimes and suspects in the investigative files the prosecution had turned over to Flowers' defense attorneys. The prosecutors had said repeatedly at trial that the only suspect seriously investigated was Flowers.

"I haven't heard anything about them," John Johnson, the investigator for the District Attorney's office, had said when questioned about the Alabama suspects at the sixth Flowers trial. "I don't know nothing about it."

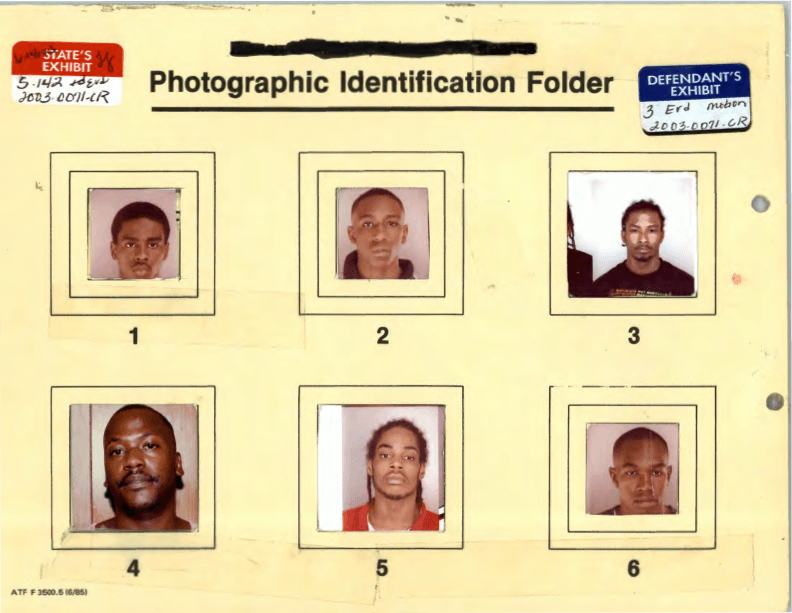

That day in October 2015, Ali was looking at a photo lineup that law enforcement had used to implicate Flowers in the Tardy case. And there he was. Marcus Presley, the gunman in the Alabama crime spree, was staring up at Ali from among the six photos in the lineup.

"It just kind of jumped out," Ali said. For Ali and the other lawyers working on Flowers' appeal at the time, this was a significant revelation. The presence of Presley in the lineup raised some questions about the testimony of law enforcement witnesses who'd said under oath that Presley was never a suspect in the Tardy case.

Evidence that prosecution witnesses may have given false testimony could potentially get Flowers' conviction overturned, said Bennett Gershman, a former prosecutor who now teaches law at Pace University.

We heard that Montgomery County was warehousing records in the old Corrulite plastics factory. So we went to check it out. But digging through the dusty, decaying files there wasn't for the faint of heart.

We uncovered 8,014 jail booking cards amid the dusty, mouse-dropping-strewn records at the old Corrulite plastics factory, where Montgomery County has been warehousing files. Four reporters spent four days photographing the cards. Each one is a hand-written record, and many were worn out and hard to read.

Taken together, the booking cards offer a snapshot — albeit an incomplete one — of arrests in the years leading up to the Tardy Furniture murders. They show a county where black men were more likely to be arrested, and the most common charges were for traffic and public drinking offenses.

Each card was filled out when a deputy booked a person into the old Montgomery County Jail. Each one has fields for the arrestee's name, address, race, gender, date of birth, date of arrest, alleged offense, and the name of the arresting officer.

We compiled cards from an 18-year span, but the data contains significant gaps. Most records we found fell into three time periods: 1981 to 1986, 1989 to 1990 and 1993 to 1996. All other years had 200 or fewer records. We had a single, stray jail record from 1971. The gaps in the data limit the conclusions we can draw.

We found 7,655 cards that listed the race of the person arrested, and they showed a clear racial disparity: 63 percent of the arrestees were black (African Americans comprised 44 percent of the county's population in the 1990 census). Though white people made up the majority of Montgomery County, they were only 33 percent of the people arrested, according to the records we recovered.

The greatest disparity relates not to race, but gender. Ninety-one percent of the booking cards we recovered were for men. Combining race and gender data, we found that a disproportionate number of black men were arrested. Black men made up 56 percent of the bookings despite being no more than a quarter of the population while white women, who made up roughly 32 percent of the population, were only 3 percent of those booked into jail.

The most common offenses in the booking cards were public drinking, driving under the influence, speeding, expired tags and driving without a license. In all, 38 percent of those arrested were charged with some kind of driving-related infraction. Twenty-one percent were booked for public drunkenness. The other charges in the data were for a mixture of serious and low-level offenses, from assault to drug trafficking.

-ALISON STEINER, DEFENSE ATTORNEY FOR CURTIS FLOWERS DURING CLOSING ARGUMENTS OF THE SIXTH TRIAL

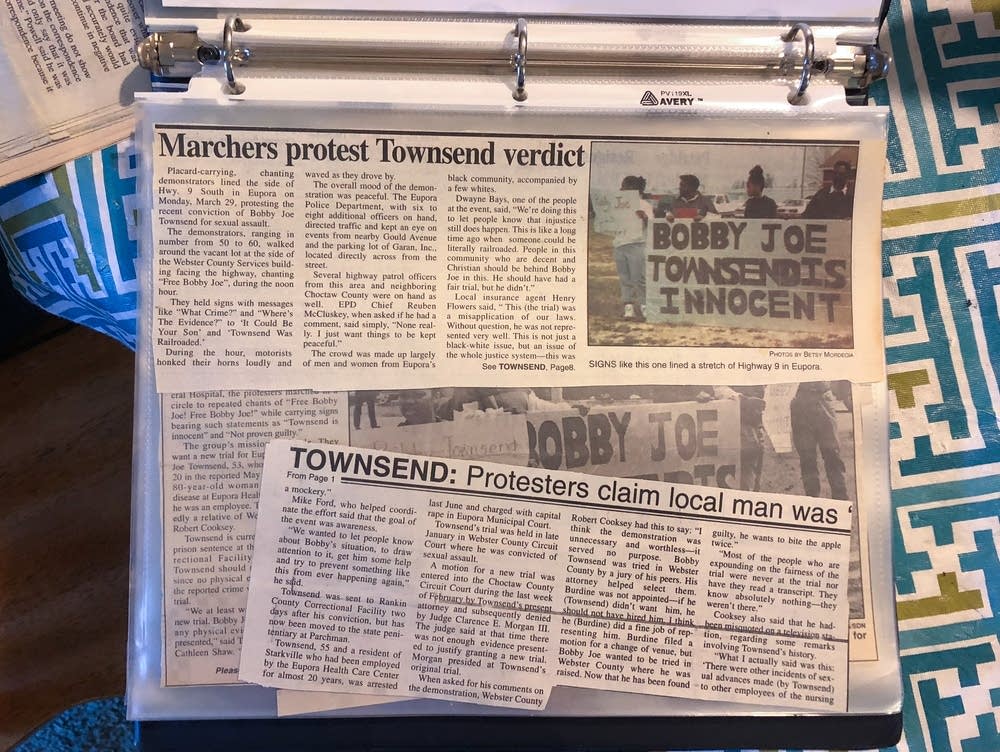

Before there were the six trials of Curtis Flowers, there were the two trials of Bobby Joe Townsend.

Townsend's trials had several similarities. The prosecutor, Doug Evans, was the same in both. So was the alleged victim, Estalee Wright, an 80-year-old white woman with dementia who happened to be the sheriff's mother-in-law. The allegations — that Townsend sexually assaulted Wright at the nursing home where he worked — were the same as well.

At the first trial, in January 1999, Townsend, who's black, faced a nearly all-white jury, and prosecutors withheld key pieces of exculpatory evidence.

Townsend was found guilty of sexual battery — forcing himself on a "physically helpless person." Judge Clarence Morgan, who would also preside over four of Curtis Flowers' trials, sentenced the 44-year-old Townsend to the maximum allowable penalty: 30 years in prison. "As far as I am concerned, it's the worst crime you could have committed on this lady, far worse than killing her," Morgan said, according to the trial transcript.

"It happened so fast and quick and next thing I know, I'm behind bars," Townsend said recently. "They put me in prison for life. Thirty years, you know, that's my life."

But there would be a second trial, two years later, and this one would be very different.

The retrial was moved to another county. Townsend was represented by a Jackson-based attorney who uncovered critical pieces of evidence that prosecutors hadn't disclosed the first time around. And there was a striking change in the jury box: This time the jury was almost all black.

Natalie Jablonski

Rehman Tungekar

Parker Yesko

Will Craft

Curtis Gilbert

Dave Mann

Andy Kruse

Catherine Winter

Chris Worthington

Gary Meister

Johnny Vince Evans

Corey Schreppel