Minnesota county sending at-risk kids to other states despite concerns about care

With its preferred juvenile correctional facility closed, Hennepin County has increased out-of-state placements 42 percent and some kids are landing in places with troubled histories.

When a juvenile correctional facility in northern Minnesota closed three years ago after news reports exposed mistreatment of minors, the state's most populous county had a dilemma: Should it send at-risk youth to another state, knowing that it probably wouldn't be the best treatment for the kid?

Experts say kids should be near family and get treatment in familiar surroundings. But few options were available in Minnesota for violent kids who also broke the law.

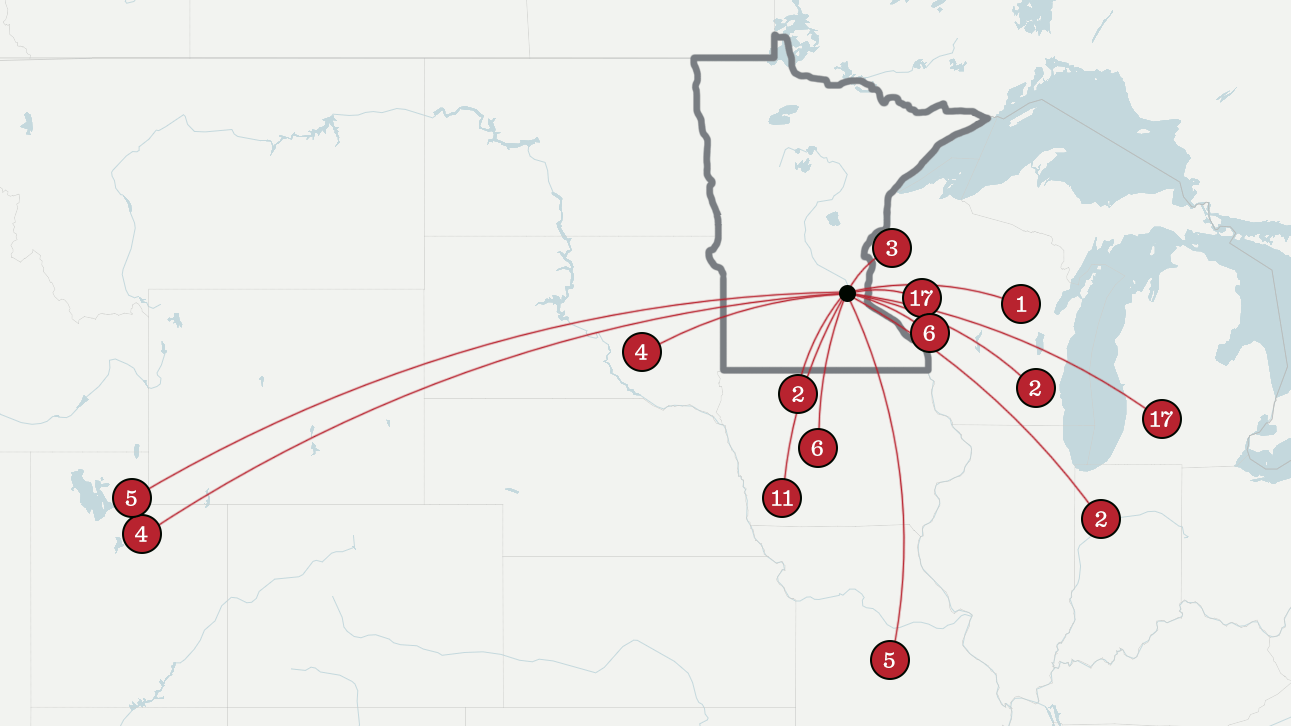

Hennepin County's choice was to send a growing number of those kids away from Minnesota. Over the past two years, the county has sent kids to other states for treatment 85 times — up from 60 during the previous two-year period — a 42 percent increase. The children, who are in the foster care system or were arrested for criminal behavior, have been sent to states as far away as Utah.

Some have landed in facilities that have had troubled histories, including allegations of sexual abuse, assault and improper behavior by staff.

The increase is driven by Hennepin County's Department of Community Corrections and Rehabilitation, which turned to facilities in Iowa and Michigan after it lost Mesabi Academy as a prime destination for kids with a recent history of violence.

Mesabi, in the tiny Iron Range city of Buhl, closed in 2016 after an APM Reports investigation revealed lax government oversight, allegations of maltreatment, mishandled claims of abuse and an unusually high number of complaints and investigations. A maltreatment investigation later found Mesabi Academy employees allowed boys as young as 12 to fight one another.

Mesabi Academy served a purpose for Hennepin County: It took in boys with troubled and violent histories that other facilities rejected.

After Mesabi's closure, the county found a new partner in Sequel Youth and Family Services, a company based in Alabama.

Of the 85 Hennepin County children sent out-of-state in 2017 and 2018, almost half were sent to facilities run by Sequel, which runs more than 40 facilities in 20 states.

Two of those Sequel facilities have been flagged for problems.

Hennepin County pulled children from Clarinda Academy in June 2018 because the Iowa facility was unable to meet "safety and well-being requirements for clients." Recent inspection reports of Lakeside Academy in Michigan show an employee aggressively slapping a child, using "unsafe" and "unwarranted" restraints and high employee turnover.

Alyssa Benson, the Quality Assurance Manager for Hennepin County Juvenile Probation with Hennepin County, said she's in regular contact with licensing officials in Michigan and has visited the facility several times. Benson also said she raised concerns about high staff turnover at Lakeside Academy and pushed it to boost pay for case managers.

The county is reluctant to send children far from their families, she said, but there are few options for aggressive youth who have committed violent offenses. "If we've exhausted all of our options in Minnesota, we will place kids out-of-state, but it is our last resort," said Benson.

Sequel responded to questions for this article with a statement saying it has taken significant steps in the past year to improve its facilities including hiring new leadership and increasing staff training.

Still, other states are wary of some Sequel operations.

The state of Washington removed kids from Clarinda Academy after a disability rights group raised concerns over the facility's treatment plan and its use of restraints. And a state lawmaker in Oregon repeatedly questioned the state's human services department for sending Oregon foster children for out-of-state treatment.

"There really was no oversight of this program, it was something that had just exploded without a plan," said Oregon state Sen. Sara Gelser. "We really didn't know where our kids were, whether they were safe, why they were far away and how we were ever going to get them home."

Gelser's a tough customer. She's travelled to Sequel facilities around the country housing Oregon foster children to check conditions and publicly questioned why Utah allowed the company's Red Rock Canyon School to remain open despite problems. Last month, Sequel announced it was going to close the facility. And a few weeks ago, Gelser met Chris Roussos, Sequel's new chief executive, who she said impressed her.

Hennepin County isn't the only Minnesota county increasingly moving kids across state lines.

Data from the Minnesota Department of Human Services show a statewide increase in the number of out-of-state placements. More than 200 kids go to other states for residential treatment every year, a 20 percent increase from a decade earlier.

'It makes you feel like you're not welcome anywhere'

There are no national statistics that show how many children are shipped across state borders for residential treatment. But experts who study juvenile justice discourage the practice because there is no evidence that residential treatment is more effective than community-based services. They argue more harm is done when a child is placed in an out-of-state facility because children lose connection to family and friends.

"Why is the grass always greener somewhere else?" asked Nate Balis, director of the Juvenile Justice Strategy Group with the Annie E. Casey Foundation. "Why do we think that we're going to get something better outside of the state?"

Hennepin County is exploring ways to keep more children closer to home. One option is redesigning the Hennepin County Home School to serve higher risk youth, said Karen Kugler, a director for the county's Department of Community Corrections and Rehabilitation.

That would be a better plan than sending kids away, said Leecia Welch, senior director of legal advocacy and child welfare at the National Center for Youth Law in Oakland, California. She said shipping a child across the border sends the message "that you are such a bad kid that there's not a single place in this entire state that wants you."

Benson said Minnesota facilities have been reluctant to accept violent kids who have committed serious offenses. The only state institution that would accept those kids is the correctional facility in Red Wing, which is considered the last resort for placing kids.

In most cases, the children sent out-of-state already have lived inside the walls of another group home, regional treatment center or foster care facility, county officials said.

Many times, children enter the system because they aren't safe at home. Those children, who sometimes experience trauma, experts say, often have a "fight or flight" response. Running away means they lose a spot in a group home and violent behavior often gets them kicked out. In many instances, a child who enters the system through the social services system crosses over into the system run by county corrections.

Some, like 18-year-old Markell Olliffe, have bounced around the system.

"I've been in placements since I was roughly 9 years old," he said. "Last time I checked I was in 36 places."

Olliffe's latest stop is the McLeod County Jail. He was charged with assault for allegedly beating a man with a tree branch.

His history shows why it's so difficult for Hennepin County to find a permanent placement for high-risk children.

The county removed Olliffe from his home in 2010 after the county cited his mother for neglect, emotional and physical abuse, according to court records. Olliffe, who is bi-racial, has been in group homes, foster care and residential treatment facilities ever since.

The population of kids sent to residential facilities is overwhelmingly African American, according to a May 2019 Annie E. Casey Foundation report. The numbers show Hennepin County is 26 times more likely to place African American kids outside of the home than white youth.

Olliffe's treatment history is a roadmap for Hennepin's preferred list of residential facilities.

He was placed at Mesabi Academy in 2014, at Iowa's Clarinda Academy in 2016 and at Michigan's Lakeside Academy in 2018.

The county sent him to those places after he ran away from group homes and committed offenses, including robbery and assault, according to Olliffe and court documents. After turning 18 in December, he left Michigan and returned to Minnesota.

Olliffe's description of each facility emphasized what he could get away with rather than what he learned. When asked if he learned anything during his time at Lakeside, he responded "not really," noting that he is currently in jail.

Olliffe said he's likely to plead guilty to his assault charge.

After spending half of his life in the foster care and juvenile justice systems, Olliffe said he felt rejected. "It makes you feel like you're not welcome anywhere," he said. "It messes with your head."

Problems at Iowa and Michigan facilities

After Mesabi Academy closed in 2016, Hennepin County turned to Sequel, which runs more than 40 facilities nationwide. The privately held company employs around 4,500 people and reported revenue of $253 million in a 2017 investor presentation. The company declined to share current revenue figures.

Like Mesabi Academy, some Sequel operations have faced allegations of staff misconduct and improper treatment.

In June last year Hennepin County abruptly removed five boys from Clarinda Academy in Iowa after finding the facility was unable to meet "safety and wellbeing requirements for clients." When asked about the decision, a spokesman for Hennepin County wouldn't elaborate.

Ramsey County also stopped sending kids there in 2018, a move that officials say was part of a broader effort to keep kids closer to their families in the Twin Cities. A spokesman for the county said Ramsey has no intention of using the facility again, though the county still has a contract with Clarinda. State data shows only one Minnesota youth was sent to Clarinda Academy this year — down from 11 in 2018 and 22 in 2017.

In October 2018, Washington state also said it was pulling its kids from Clarinda after a disability rights group released a study showing the facility failed to provide appropriate treatment to its foster children, segregated them from society and excessively used physical restraints. Sequel disputed some of the study's findings.

In 2016, the year before Hennepin County started sending kids to Clarinda, a former staffer was convicted of sexual misconduct for abusing a 17-year-old girl there.

While Hennepin County no longer uses Clarinda Academy, it continues to rely on another Sequel operation — Lakeside Academy, more than 500 miles away from Minneapolis in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Lakeside Academy is flashing warning signs, too: 911 dispatch records show that since the beginning of 2018, police were called to its address 78 times, not counting fire alarms, animal complaints, assistance to other departments or other minor matters. The allegations included seven reports of child abuse or neglect, 16 assaults and 15 calls regarding criminal sexual conduct. (The records don't show whether Lakeside workers or residents were the subject of the complaint.)

Special investigations by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services found licensing violations at Lakeside Academy six times last year. One reported that a staffer slapped and pushed a resident "in an aggressive manner." Another found a resident was restrained four times in a way that was "unwarranted" as well as "inappropriate or unsafe." The resident received a large rugburn on her face but did not receive medical treatment beyond basic cleaning and bandaging of the wound until two days later.

Other violations related to inadequate supervision or unprofessional behavior by staff. Last August, a state investigative report found: "Overall, reports from both staff and residents support the lack of appropriate staff supervision and interactions with residents. Reports support that staff are not following the policies and procedure for appropriate interactions with residents as outlined in the facilities guidelines for staff. As such, staff are demonstrating an inability to perform the functions of their job as they all know the requirements and yet do not follow them."

The facility's annual inspection in October shows that nearly 40 percent of Lakeside employees had been hired within the previous year. Sequel said Roussos, its CEO, wasn't available for an interview, but wrote that it was working, "... very hard to continually improve our practices and ensure that we are providing the best care possible for our students."

As evidence, it pointed to its new leadership team, hundreds of additional security cameras, and a new system that uses padded shields to reduce the need to physically restrain kids. It has also increased the frequency of staff training and strengthened the use of background checks on potential employees.

Out-of-state placements increase despite national reduction in total placements

Despite the increase in the number of Hennepin County youth being sent out-of-state, the number of overall child placements by the county dropped 36 percent between 2015 and 2018.

The reduction is part of a larger national trend that shows a 47 percent reduction in out-of-home placements from 2006 through 2017, according to federal data.

The decrease, experts say, is a result of a national effort to focus on providing services to children — from mental health care to chemical dependency treatment — within the community rather than focusing on punishment.

But officials will still place children in residential treatment if they continue to commit crimes or are violent.

That's one bet Sequel is making to grow its business.

A 2017 report to prospective investors, created under an earlier executive, characterized the marketplace for residential treatment for juveniles as a "highly fragmented industry ripe for consolidation."

About 500 of the 2,000 juveniles in Sequel facilities are children from another state, the company said. But a Sequel executive recently acknowledged that it's usually best to keep kids close to home.

"Many states do not have facilities or a network of services, which means the young people are sent out of state," said Mandy Moses, the chief operating officer. "This is not ideal, because the kids are not in their home communities. They're not with their friends and not with their families."

The presiding judge of the juvenile court in Hennepin County said he's reluctant to place a child outside of the home and will only agree to it if the county can prove the facility is best for the child.

Judge David Piper said he typically takes feedback from county probation officers and social services, prosecutors, the child's family and defense attorneys. Piper said it was alarming to learn of Hennepin's increase in out-of-state placements but stressed they may be better than placing a child in Minnesota's only state-run juvenile correctional facility in Red Wing, Minnesota, or sending the child to adult court.

"We don't like placing children out of the state of Minnesota unless we absolutely have to because of distance, transparency and accountability," he said.

Hennepin County officials say they are in regular contact with any child placed in another state and visit each site regularly.

While Hennepin County says it wants to reduce out-of-state placements, Ramsey County has done so. In 2016, 51 Ramsey County youth were sent to another state. In 2018, the number dropped to 24.

Officials there credit an effort over the past 15 years that included input from judges, the county attorney's office, social services and probation. It resulted in a system that offered more local treatment choices for juveniles.

"It takes quite a while for a big shift like that to occur," said John Klavins, director of Ramsey County Corrections. "We're sitting here 10 or 15 years later with these significant numbers actually playing out now."

Ramsey County's reduction in out-of-home placements also prompted the county to close Boys Totem Town this month, a 36-bed juvenile correctional facility that had operated for 106 years.